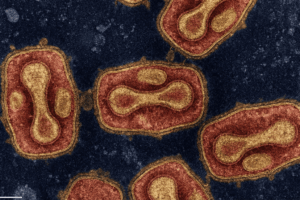

A recent RNA metagenomic study conducted on wild-caught northern short-tailed shrews in Alabama led to the discovery of a novel henipavirus, identified as Camp Hill virus (CHV). Henipaviruses are zoonotic, negative-sense RNA viruses known for their ability to cross species barriers and infect a variety of mammals including humans.

These viruses often cause severe illnesses, like respiratory infections and encephalitis, with high fatality rates. Hendra virus was first identified in Australia, and Nipah virus has caused significant outbreaks in Southeast Asia. These viruses have spurred global health concerns due to their potential to spread to humans.

In 2018, the study discovered another henipavirus i.e., Langya virus (LayV), which was linked to human infections in China. LayV was found primarily in shrews, though it has also been detected in other animals, like goats and dogs. This discovery raised awareness about the role of shrews in the transmission of henipaviruses, further underlining the importance of monitoring these small mammals for emerging zoonotic diseases.

The Alabama study, led by a team from Auburn University, focused on four northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda) that were captured in the wild in 2021. Tissues from these shrews, including skin, heart, liver, kidneys, and brain, were collected and analyzed through RNA sequencing. The research revealed a new virus that shared genetic similarities with other henipaviruses, especially those found in shrews from Eurasia. This virus was named Camp Hill virus (CHV) after the location where the shrews were captured.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that CHV is a part of a shrew-specific clade within the Henipavirus genus. The viral genome showed a distinct pattern as an open reading frame between the M and F genes that has been predicted in other shrew-associated henipaviruses as LayV which was predominantly detected in kidney tissues of the shrews, suggesting the renal tropism.

The discovery of CHV raises significant concerns regarding the potential for human infection given the known fatality rates of other henipaviruses. The shrew species involved B. brevicauda is widespread across central and eastern North America, often residing in areas that overlap with human populations including agricultural and urban environments. Despite their territorial nature these shrews are active and can have extensive home ranges occasionally coming into contact with humans.

Previous studies have also linked B. brevicauda shrews to other viral infections like Camp Ripley virus (Orthohantavirus) and Powassan virus (Orthoflavivirus) both of which have been associated with severe human diseases. The presence of multiple viruses in these shrews suggests that they may serve as hosts for a variety of potentially dangerous pathogens.

While direct human interactions with shrews are relatively rare, the discovery of CHV raises important questions about the broader ecological risks of zoonotic spillovers. The risk to humans from other henipaviruses likely stems from direct contact with infected animals or exposure to their excretions. This underscores the need for further investigation into how such viruses are transmitted and the development of strategies to mitigate potential outbreaks.

This discovery highlights the growing importance of wildlife surveillance in detecting emerging viruses in regions where human and animal habitats overlap. With the identification of CHV, researchers are now calling for increased vigilance and research to better understand the role of shrews as reservoirs for zoonotic viruses and the risks they pose to public health.

Reference: Parry RH, Yamada KYH, Hood WR, et al. Henipavirus in northern short-tailed shrew, Alabama, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2025;31(2). doi:10.3201/eid3102.241155