Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease. It is transmitted to humans through bites from infected black-legged ticks. The epidemiology of B. burgdorferi is influenced by various factors, including the distribution of the tick vector, host populations, and environmental conditions.

Geographic distribution: The tick species that transmit B. burgdorferi is found primarily in the mid-Atlantic and northeastern regions of the United States. Even so, cases have been reported in other parts of the country, including the West Coast.

The risk of acquiring Lyme disease is highest during the spring and summer when ticks are most active. Small mammals, such as mice and chipmunks, are the primary hosts for the black-legged tick. The abundance of these hosts and the presence of other vertebrate hosts can impact the prevalence of the bacteria in tick populations.

Environmental factors, like temperature and humidity, can impact tick survival and activity. Changes in these conditions can impact the distribution and prevalence of the tick vector, which in turn can impact the incidence of Lyme disease.

Surveillance programs are in place to monitor the incidence and distribution of Lyme disease. It includes tracking human cases, tick populations, and animal reservoirs. As a result, there is a growing understanding of the epidemiology of B. burgdorferi and the factors that influence its spread.

Scientific Classification:

Structure:

Borrelia burgdorferi is a spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacteria approximately 10-25 microns long and 0.2-0.5 microns in diameter. The unique structure of B. burgdorferi includes multiple axial flagella that run along the length of the cell between the outer membrane and the peptidoglycan layer.

The periplasmic flagellar region is divided into three central regions, the cytoplasmic ribbon and the outer membrane. The periplasmic flagellar region contains the axial flagella, which provides motility to the bacteria.

The cytoplasmic ribbon contains bacterial DNA, ribosomes, and other cellular machinery for metabolic processes. The outer membrane comprises lipoproteins responsible for interacting with the host and evading the host’s immune system.

Borrelia burgdorferi is also known for its ability to change its surface proteins through antigenic variation, which allows the bacteria to avoid detection by the host immune system, leading to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Overall, the unique structure of B. burgdorferi, including its axial flagella and the lipoprotein-rich outer membrane, contributes to its pathogenicity and ability to cause Lyme disease in humans.

The most well-known antigenic type is OspA, which is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during the tick phase of its lifecycle. OspA is a significant surface antigen used as a target for vaccines against Lyme disease. However, during the mammalian phase of the bacteria’s lifecycle, OspA expression is downregulated, and OspC is upregulated.

OspC is another surface antigen expressed during the mammalian phase of Borrelia burgdorferi’s lifecycle. OspC is thought to be involved in establishing host infection and evading the host’s immune response. Like OspA, OspC is also antigenically variable, with multiple strains expressing different protein variants.

In addition to OspA and OspC, B. burgdorferi also expresses several other surface antigens, including decorin-binding protein A (DbpA), BBA64, and VlsE, among others. These antigens are essential in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, and like OspA and OspC, they are subject to antigenic variation.

There are three antigenic types or species of B. burgdorferi that are known to cause human disease:

The pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi involves multiple stages and mechanisms.

The spirochetes enter the host’s bloodstream through the tick bite and disseminate to various tissues and organs. The outer surface protein C (OspC) is critical for the initial attachment, colonization, and dissemination of the spirochetes. B. burgdorferi expresses various adhesins and proteases to facilitate its attachment and penetration of host tissues.

B. burgdorferi possesses several mechanisms to evade host immune responses, including antigenic variation, immune suppression, and manipulation of host factors.

B. can change its surface antigens to avoid recognition by the immune system. The bacterium can produce immunosuppressive factors, such as the protein BBA57, to inhibit T cell activation and cytokine production.

B. burgdorferi can also manipulate the host’s immune responses by inducing activation of regulatory T cells and skewing the Th1/Th2 balance towards a Th2 response, impairing the host’s ability to eliminate the infection.

B. burgdorferi can cause tissue damage and inflammation through several mechanisms, including direct tissue invasion, activation of inflammatory mediators, and recruitment of immune cells.

The spirochetes can invade various tissues and organs, including the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system, leading to tissue destruction and dysfunction.

B. burgdorferi can evade the host immune response through various mechanisms, including antigenic variation, cytokine production suppression, and complement activation inhibition. It can lead to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Upon infection, the innate immune system is activated, which triggers the release of cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment of various immune cells to the site of infection. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages arrive at the site of infection. These cells engulf and destroy the bacteria through phagocytosis.

The adaptive immune response involves activating T and B cells, which work together to eliminate the infection. T cells recognize and respond to specific antigens presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and macrophages. Activated T cells then activate B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the B. burgdorferi antigens.

These antibodies can then help clear the bacteria from the body through various mechanisms, including opsonization, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

In addition to the immune response, host defense against B. burgdorferi involves non-immune mechanisms, such as the skin’s physical barrier to prevent tick bites and behavioral modifications to avoid areas where ticks are likely to present.

The clinical manifestations of Borrelia burgdorferi infection can contrast depending on the stage of the disease. The early stage of the disease, known as early localized Lyme disease, typically presents with a characteristic rash called erythema migrans (EM), which usually appears at the tick bite site within 3 to 30 days. The EM rash usually has a circular or oval shape with a central clearing and can expand over time.

Other symptoms in this stage may include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, swollen lymph nodes, and neurological symptoms, such as meningitis, facial palsy, and radiculoneuropathy. In the late stage of the disease, known as late disseminated Lyme disease, patients may develop arthritis in the large joints, such as the knees, and neurological symptoms, such as encephalopathy, cognitive impairment, and peripheral neuropathy.

Not all patients with B. burgdorferi infection will develop the symptoms mentioned above. In addition, some patients may have atypical or nonspecific symptoms, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and depression. Therefore, a high index of intuition is required for diagnosis, and laboratory testing is usually necessary to confirm Lyme disease.

In addition to Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi can also cause other diseases, including:

It’s important to note that while these diseases can be severe, not all cases of B. burgdorferi infection result in severe disease.

There are several diagnosis methods used to detect the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, including:

Taking these precautions can reduce your risk of exposure to B. burgdorferi and prevent Lyme disease.

Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease. It is transmitted to humans through bites from infected black-legged ticks. The epidemiology of B. burgdorferi is influenced by various factors, including the distribution of the tick vector, host populations, and environmental conditions.

Geographic distribution: The tick species that transmit B. burgdorferi is found primarily in the mid-Atlantic and northeastern regions of the United States. Even so, cases have been reported in other parts of the country, including the West Coast.

The risk of acquiring Lyme disease is highest during the spring and summer when ticks are most active. Small mammals, such as mice and chipmunks, are the primary hosts for the black-legged tick. The abundance of these hosts and the presence of other vertebrate hosts can impact the prevalence of the bacteria in tick populations.

Environmental factors, like temperature and humidity, can impact tick survival and activity. Changes in these conditions can impact the distribution and prevalence of the tick vector, which in turn can impact the incidence of Lyme disease.

Surveillance programs are in place to monitor the incidence and distribution of Lyme disease. It includes tracking human cases, tick populations, and animal reservoirs. As a result, there is a growing understanding of the epidemiology of B. burgdorferi and the factors that influence its spread.

Scientific Classification:

Structure:

Borrelia burgdorferi is a spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacteria approximately 10-25 microns long and 0.2-0.5 microns in diameter. The unique structure of B. burgdorferi includes multiple axial flagella that run along the length of the cell between the outer membrane and the peptidoglycan layer.

The periplasmic flagellar region is divided into three central regions, the cytoplasmic ribbon and the outer membrane. The periplasmic flagellar region contains the axial flagella, which provides motility to the bacteria.

The cytoplasmic ribbon contains bacterial DNA, ribosomes, and other cellular machinery for metabolic processes. The outer membrane comprises lipoproteins responsible for interacting with the host and evading the host’s immune system.

Borrelia burgdorferi is also known for its ability to change its surface proteins through antigenic variation, which allows the bacteria to avoid detection by the host immune system, leading to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Overall, the unique structure of B. burgdorferi, including its axial flagella and the lipoprotein-rich outer membrane, contributes to its pathogenicity and ability to cause Lyme disease in humans.

The most well-known antigenic type is OspA, which is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during the tick phase of its lifecycle. OspA is a significant surface antigen used as a target for vaccines against Lyme disease. However, during the mammalian phase of the bacteria’s lifecycle, OspA expression is downregulated, and OspC is upregulated.

OspC is another surface antigen expressed during the mammalian phase of Borrelia burgdorferi’s lifecycle. OspC is thought to be involved in establishing host infection and evading the host’s immune response. Like OspA, OspC is also antigenically variable, with multiple strains expressing different protein variants.

In addition to OspA and OspC, B. burgdorferi also expresses several other surface antigens, including decorin-binding protein A (DbpA), BBA64, and VlsE, among others. These antigens are essential in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, and like OspA and OspC, they are subject to antigenic variation.

There are three antigenic types or species of B. burgdorferi that are known to cause human disease:

The pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi involves multiple stages and mechanisms.

The spirochetes enter the host’s bloodstream through the tick bite and disseminate to various tissues and organs. The outer surface protein C (OspC) is critical for the initial attachment, colonization, and dissemination of the spirochetes. B. burgdorferi expresses various adhesins and proteases to facilitate its attachment and penetration of host tissues.

B. burgdorferi possesses several mechanisms to evade host immune responses, including antigenic variation, immune suppression, and manipulation of host factors.

B. can change its surface antigens to avoid recognition by the immune system. The bacterium can produce immunosuppressive factors, such as the protein BBA57, to inhibit T cell activation and cytokine production.

B. burgdorferi can also manipulate the host’s immune responses by inducing activation of regulatory T cells and skewing the Th1/Th2 balance towards a Th2 response, impairing the host’s ability to eliminate the infection.

B. burgdorferi can cause tissue damage and inflammation through several mechanisms, including direct tissue invasion, activation of inflammatory mediators, and recruitment of immune cells.

The spirochetes can invade various tissues and organs, including the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system, leading to tissue destruction and dysfunction.

B. burgdorferi can evade the host immune response through various mechanisms, including antigenic variation, cytokine production suppression, and complement activation inhibition. It can lead to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Upon infection, the innate immune system is activated, which triggers the release of cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment of various immune cells to the site of infection. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages arrive at the site of infection. These cells engulf and destroy the bacteria through phagocytosis.

The adaptive immune response involves activating T and B cells, which work together to eliminate the infection. T cells recognize and respond to specific antigens presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and macrophages. Activated T cells then activate B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the B. burgdorferi antigens.

These antibodies can then help clear the bacteria from the body through various mechanisms, including opsonization, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

In addition to the immune response, host defense against B. burgdorferi involves non-immune mechanisms, such as the skin’s physical barrier to prevent tick bites and behavioral modifications to avoid areas where ticks are likely to present.

The clinical manifestations of Borrelia burgdorferi infection can contrast depending on the stage of the disease. The early stage of the disease, known as early localized Lyme disease, typically presents with a characteristic rash called erythema migrans (EM), which usually appears at the tick bite site within 3 to 30 days. The EM rash usually has a circular or oval shape with a central clearing and can expand over time.

Other symptoms in this stage may include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, swollen lymph nodes, and neurological symptoms, such as meningitis, facial palsy, and radiculoneuropathy. In the late stage of the disease, known as late disseminated Lyme disease, patients may develop arthritis in the large joints, such as the knees, and neurological symptoms, such as encephalopathy, cognitive impairment, and peripheral neuropathy.

Not all patients with B. burgdorferi infection will develop the symptoms mentioned above. In addition, some patients may have atypical or nonspecific symptoms, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and depression. Therefore, a high index of intuition is required for diagnosis, and laboratory testing is usually necessary to confirm Lyme disease.

In addition to Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi can also cause other diseases, including:

It’s important to note that while these diseases can be severe, not all cases of B. burgdorferi infection result in severe disease.

There are several diagnosis methods used to detect the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, including:

Taking these precautions can reduce your risk of exposure to B. burgdorferi and prevent Lyme disease.

Borrelia burgdorferi causes Lyme disease. It is transmitted to humans through bites from infected black-legged ticks. The epidemiology of B. burgdorferi is influenced by various factors, including the distribution of the tick vector, host populations, and environmental conditions.

Geographic distribution: The tick species that transmit B. burgdorferi is found primarily in the mid-Atlantic and northeastern regions of the United States. Even so, cases have been reported in other parts of the country, including the West Coast.

The risk of acquiring Lyme disease is highest during the spring and summer when ticks are most active. Small mammals, such as mice and chipmunks, are the primary hosts for the black-legged tick. The abundance of these hosts and the presence of other vertebrate hosts can impact the prevalence of the bacteria in tick populations.

Environmental factors, like temperature and humidity, can impact tick survival and activity. Changes in these conditions can impact the distribution and prevalence of the tick vector, which in turn can impact the incidence of Lyme disease.

Surveillance programs are in place to monitor the incidence and distribution of Lyme disease. It includes tracking human cases, tick populations, and animal reservoirs. As a result, there is a growing understanding of the epidemiology of B. burgdorferi and the factors that influence its spread.

Scientific Classification:

Structure:

Borrelia burgdorferi is a spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacteria approximately 10-25 microns long and 0.2-0.5 microns in diameter. The unique structure of B. burgdorferi includes multiple axial flagella that run along the length of the cell between the outer membrane and the peptidoglycan layer.

The periplasmic flagellar region is divided into three central regions, the cytoplasmic ribbon and the outer membrane. The periplasmic flagellar region contains the axial flagella, which provides motility to the bacteria.

The cytoplasmic ribbon contains bacterial DNA, ribosomes, and other cellular machinery for metabolic processes. The outer membrane comprises lipoproteins responsible for interacting with the host and evading the host’s immune system.

Borrelia burgdorferi is also known for its ability to change its surface proteins through antigenic variation, which allows the bacteria to avoid detection by the host immune system, leading to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Overall, the unique structure of B. burgdorferi, including its axial flagella and the lipoprotein-rich outer membrane, contributes to its pathogenicity and ability to cause Lyme disease in humans.

The most well-known antigenic type is OspA, which is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during the tick phase of its lifecycle. OspA is a significant surface antigen used as a target for vaccines against Lyme disease. However, during the mammalian phase of the bacteria’s lifecycle, OspA expression is downregulated, and OspC is upregulated.

OspC is another surface antigen expressed during the mammalian phase of Borrelia burgdorferi’s lifecycle. OspC is thought to be involved in establishing host infection and evading the host’s immune response. Like OspA, OspC is also antigenically variable, with multiple strains expressing different protein variants.

In addition to OspA and OspC, B. burgdorferi also expresses several other surface antigens, including decorin-binding protein A (DbpA), BBA64, and VlsE, among others. These antigens are essential in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, and like OspA and OspC, they are subject to antigenic variation.

There are three antigenic types or species of B. burgdorferi that are known to cause human disease:

The pathogenesis of B. burgdorferi involves multiple stages and mechanisms.

The spirochetes enter the host’s bloodstream through the tick bite and disseminate to various tissues and organs. The outer surface protein C (OspC) is critical for the initial attachment, colonization, and dissemination of the spirochetes. B. burgdorferi expresses various adhesins and proteases to facilitate its attachment and penetration of host tissues.

B. burgdorferi possesses several mechanisms to evade host immune responses, including antigenic variation, immune suppression, and manipulation of host factors.

B. can change its surface antigens to avoid recognition by the immune system. The bacterium can produce immunosuppressive factors, such as the protein BBA57, to inhibit T cell activation and cytokine production.

B. burgdorferi can also manipulate the host’s immune responses by inducing activation of regulatory T cells and skewing the Th1/Th2 balance towards a Th2 response, impairing the host’s ability to eliminate the infection.

B. burgdorferi can cause tissue damage and inflammation through several mechanisms, including direct tissue invasion, activation of inflammatory mediators, and recruitment of immune cells.

The spirochetes can invade various tissues and organs, including the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system, leading to tissue destruction and dysfunction.

B. burgdorferi can evade the host immune response through various mechanisms, including antigenic variation, cytokine production suppression, and complement activation inhibition. It can lead to chronic infection and long-term complications.

Upon infection, the innate immune system is activated, which triggers the release of cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment of various immune cells to the site of infection. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages arrive at the site of infection. These cells engulf and destroy the bacteria through phagocytosis.

The adaptive immune response involves activating T and B cells, which work together to eliminate the infection. T cells recognize and respond to specific antigens presented by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and macrophages. Activated T cells then activate B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the B. burgdorferi antigens.

These antibodies can then help clear the bacteria from the body through various mechanisms, including opsonization, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.

In addition to the immune response, host defense against B. burgdorferi involves non-immune mechanisms, such as the skin’s physical barrier to prevent tick bites and behavioral modifications to avoid areas where ticks are likely to present.

The clinical manifestations of Borrelia burgdorferi infection can contrast depending on the stage of the disease. The early stage of the disease, known as early localized Lyme disease, typically presents with a characteristic rash called erythema migrans (EM), which usually appears at the tick bite site within 3 to 30 days. The EM rash usually has a circular or oval shape with a central clearing and can expand over time.

Other symptoms in this stage may include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, swollen lymph nodes, and neurological symptoms, such as meningitis, facial palsy, and radiculoneuropathy. In the late stage of the disease, known as late disseminated Lyme disease, patients may develop arthritis in the large joints, such as the knees, and neurological symptoms, such as encephalopathy, cognitive impairment, and peripheral neuropathy.

Not all patients with B. burgdorferi infection will develop the symptoms mentioned above. In addition, some patients may have atypical or nonspecific symptoms, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue, and depression. Therefore, a high index of intuition is required for diagnosis, and laboratory testing is usually necessary to confirm Lyme disease.

In addition to Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi can also cause other diseases, including:

It’s important to note that while these diseases can be severe, not all cases of B. burgdorferi infection result in severe disease.

There are several diagnosis methods used to detect the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, including:

Taking these precautions can reduce your risk of exposure to B. burgdorferi and prevent Lyme disease.

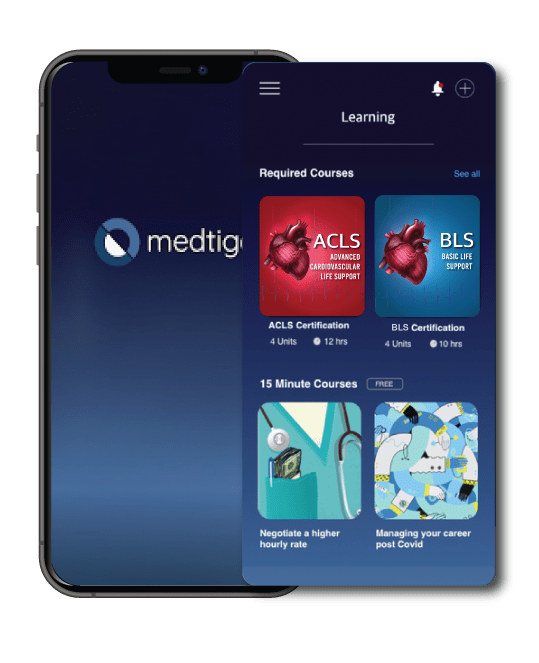

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

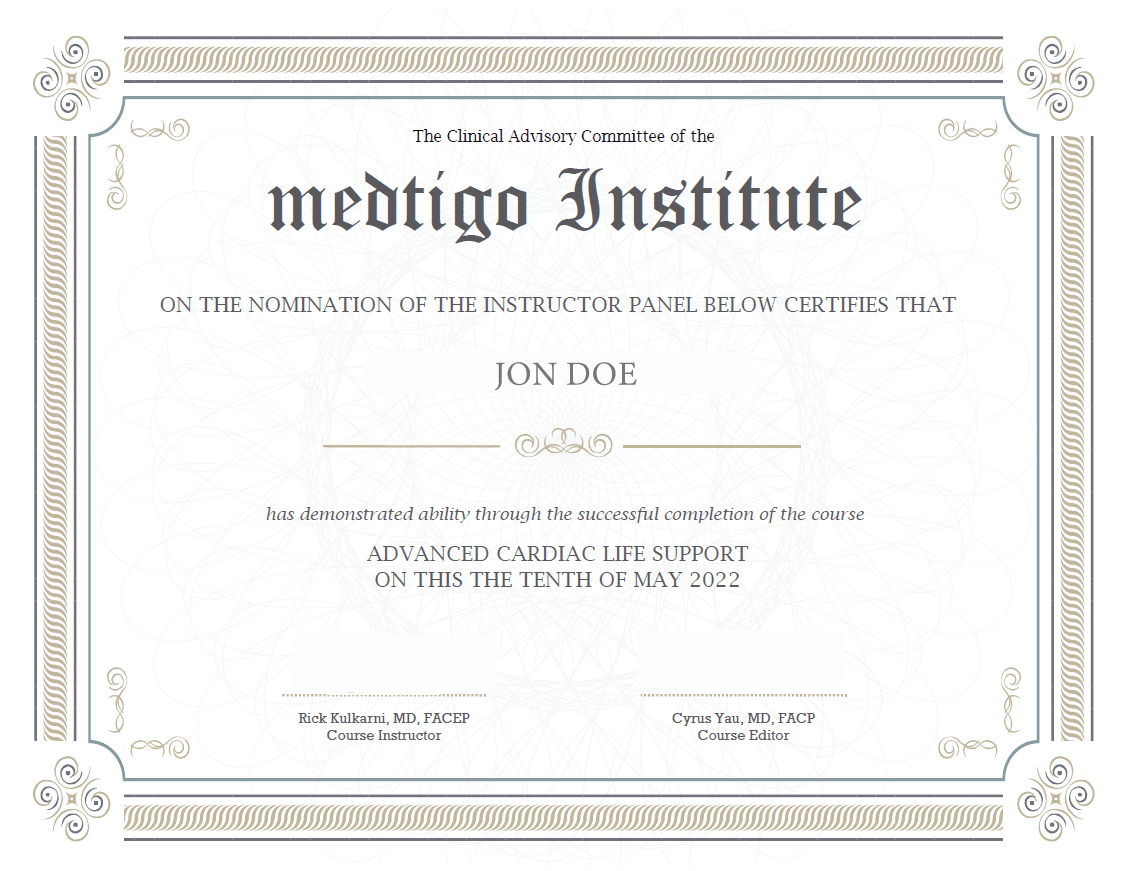

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

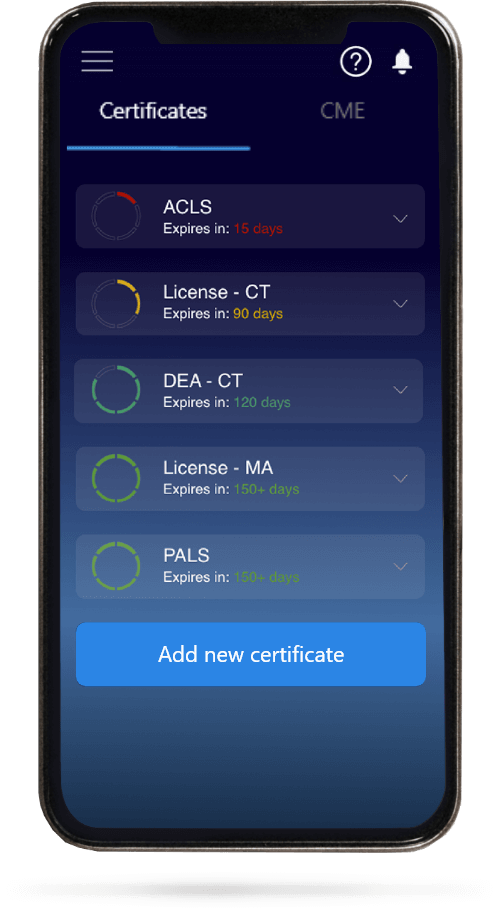

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.