CYP2D6-Guided Opioid Prescribing Fails to Improve Postoperative Pain in ADOPT PGx Randomized Trial

February 23, 2026

Background

Disease-related changes in appetite stem from several physiological and psychological factors. Many chronic illnesses cause systemic inflammation, metabolic changes, and alterations in nutrient uptake that can dysregulate appetite. Neuropsychological factors including stress, depression and thereby a reduced quality of life, also depauperate the process of appetite in chronic disease. Non-cognitive factors like cachexia in cancer, peripheral oedema in heart failure decrease hunger because the question causes general discomfort. In addition, therapies are also known to have side effects such as nausea and change in taste which can lead to worsening of appetite loss. The management of these problems usually requires medical nutrition therapy, symptom control and psychological interventions.

Epidemiology

It is prevalent in chronic conditions: 70% in cancer patients, especially in the terminal stage or those receiving chemotherapy, 40 to 50% in stage 4 and 5 CKD patients, Modest 30-50% in COPD due to energy demand and breathing difficulties, and mild 20-30% in heart failure patients due to fluid accumulation and oedema.

The changes of appetite are experienced by all age populations though the elderly are more vulnerable. It has been established that gender differences exist, but many of these differences depend on the disease or the study conducted.

Anatomy

Pathophysiology

Etiology

Chronic diseases cause inflammation, which activates cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 that inhibit the starvation centers in the brain, leading to changes in hunger signals. Both cancer and CKD can lead to cachexia, which leads to severe weight loss and muscle wasting because the body energy use rate is high and the desire to eat is low.

Conditions like cancer, COPD, and treatments through chemo can make foods unappetizing, and diseases like CKD can aggressively impact one’s digestive system.

Abnormalities in the hormonal regulation of appetite, particularly the signals of leptin and ghrelin are likely to result in alteration of appetite.

Genetics

Prognostic Factors

Disease Severity and Stage: At more advanced stages and especially if it is a severe case, the affected person is likely to lose his/her appetite.

Inflammatory Markers: As the appetite and the disease severity worsens, the cytokine levels are likely to be high.

Metabolic Status: Cachexia and poor nutritional status used in this study affect appetite and prognosis.

Gastrointestinal Health: Conditions such as the nauseating effect or poor digestion also will contribute to reduced appetite.

Hormonal and Neurotransmitter Levels: Hormonal abnormalities and neurotransmitters for hunger contributors are also include.

Clinical History

Age Group

Appetite changes could also be due to chronic diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis or cystic fibrosis in children, adults, and the elderly. In this case, children may develop anorexia and may lose weight whereas, adults may develop anorexia, early satiety and may start to lose weight unintentionally. Older adults may present with many disease-related issues affecting their appetite and uptake of foods due to multiple comorbidities and age-related physiology alterations.

Physical Examination

Age group

Associated comorbidity

Associated activity

Acuity of presentation

Differential Diagnoses

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Procedures

Histologic Findings

Staging

Treatment Paradigm

Control the Chronic Disease: Ensure these core disorders are well managed (e.g., cancer, chronic kidney disease) and then address symptoms such as pain, nausea, and depression to enhance appetite.

Nutritional Support: Modify the diet according to patient’s choice and provide small high-energy dense and high-protein meals and if needed appetite enhancers such as megestrol acetate or corticosteroids.

Psychosocial Support: Psychotherapy or counseling to address the psychological component, and mutual support through purposeful psychological support groups.

Medical Interventions: Promote appetite stimulating agents like cannabinoids and antidepressants; Consider tube feeding in very severe conditions where oral intake is compromised.

Monitoring and Follow-Up: Weight monitoring at least weekly and/or other anthropometric measures, nutritional history, and corresponding changes in the treatment plan.

by Stage

by Modality

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Surgical Interventions

Hormone Therapy

Immunotherapy

Hyperthermia

Photodynamic Therapy

Stem Cell Transplant

Targeted Therapy

Palliative Care

use-of-a-non-pharmacological-approach-for-treating-appetite-secondary-to-chronic-disease

Role of Appetite stimulants

use-of-intervention-with-a-procedure-in-treating-appetite-secondary-to-chronic-disease

use-of-phases-in-managing-appetite-secondary-to-chronic-disease

Medication

Indicated for Decreased Appetite Secondary to Chronic Disease :

2

mg

Orally

4 times a week; then 4 mg orally 4 times a week

Future Trends

Disease-related changes in appetite stem from several physiological and psychological factors. Many chronic illnesses cause systemic inflammation, metabolic changes, and alterations in nutrient uptake that can dysregulate appetite. Neuropsychological factors including stress, depression and thereby a reduced quality of life, also depauperate the process of appetite in chronic disease. Non-cognitive factors like cachexia in cancer, peripheral oedema in heart failure decrease hunger because the question causes general discomfort. In addition, therapies are also known to have side effects such as nausea and change in taste which can lead to worsening of appetite loss. The management of these problems usually requires medical nutrition therapy, symptom control and psychological interventions.

It is prevalent in chronic conditions: 70% in cancer patients, especially in the terminal stage or those receiving chemotherapy, 40 to 50% in stage 4 and 5 CKD patients, Modest 30-50% in COPD due to energy demand and breathing difficulties, and mild 20-30% in heart failure patients due to fluid accumulation and oedema.

The changes of appetite are experienced by all age populations though the elderly are more vulnerable. It has been established that gender differences exist, but many of these differences depend on the disease or the study conducted.

Chronic diseases cause inflammation, which activates cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 that inhibit the starvation centers in the brain, leading to changes in hunger signals. Both cancer and CKD can lead to cachexia, which leads to severe weight loss and muscle wasting because the body energy use rate is high and the desire to eat is low.

Conditions like cancer, COPD, and treatments through chemo can make foods unappetizing, and diseases like CKD can aggressively impact one’s digestive system.

Abnormalities in the hormonal regulation of appetite, particularly the signals of leptin and ghrelin are likely to result in alteration of appetite.

Disease Severity and Stage: At more advanced stages and especially if it is a severe case, the affected person is likely to lose his/her appetite.

Inflammatory Markers: As the appetite and the disease severity worsens, the cytokine levels are likely to be high.

Metabolic Status: Cachexia and poor nutritional status used in this study affect appetite and prognosis.

Gastrointestinal Health: Conditions such as the nauseating effect or poor digestion also will contribute to reduced appetite.

Hormonal and Neurotransmitter Levels: Hormonal abnormalities and neurotransmitters for hunger contributors are also include.

Age Group

Appetite changes could also be due to chronic diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis or cystic fibrosis in children, adults, and the elderly. In this case, children may develop anorexia and may lose weight whereas, adults may develop anorexia, early satiety and may start to lose weight unintentionally. Older adults may present with many disease-related issues affecting their appetite and uptake of foods due to multiple comorbidities and age-related physiology alterations.

Control the Chronic Disease: Ensure these core disorders are well managed (e.g., cancer, chronic kidney disease) and then address symptoms such as pain, nausea, and depression to enhance appetite.

Nutritional Support: Modify the diet according to patient’s choice and provide small high-energy dense and high-protein meals and if needed appetite enhancers such as megestrol acetate or corticosteroids.

Psychosocial Support: Psychotherapy or counseling to address the psychological component, and mutual support through purposeful psychological support groups.

Medical Interventions: Promote appetite stimulating agents like cannabinoids and antidepressants; Consider tube feeding in very severe conditions where oral intake is compromised.

Monitoring and Follow-Up: Weight monitoring at least weekly and/or other anthropometric measures, nutritional history, and corresponding changes in the treatment plan.

Nutrition

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Nephrology

Nutrition

Nephrology

Nutrition

Nephrology

Nutrition

Disease-related changes in appetite stem from several physiological and psychological factors. Many chronic illnesses cause systemic inflammation, metabolic changes, and alterations in nutrient uptake that can dysregulate appetite. Neuropsychological factors including stress, depression and thereby a reduced quality of life, also depauperate the process of appetite in chronic disease. Non-cognitive factors like cachexia in cancer, peripheral oedema in heart failure decrease hunger because the question causes general discomfort. In addition, therapies are also known to have side effects such as nausea and change in taste which can lead to worsening of appetite loss. The management of these problems usually requires medical nutrition therapy, symptom control and psychological interventions.

It is prevalent in chronic conditions: 70% in cancer patients, especially in the terminal stage or those receiving chemotherapy, 40 to 50% in stage 4 and 5 CKD patients, Modest 30-50% in COPD due to energy demand and breathing difficulties, and mild 20-30% in heart failure patients due to fluid accumulation and oedema.

The changes of appetite are experienced by all age populations though the elderly are more vulnerable. It has been established that gender differences exist, but many of these differences depend on the disease or the study conducted.

Chronic diseases cause inflammation, which activates cytokines such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 that inhibit the starvation centers in the brain, leading to changes in hunger signals. Both cancer and CKD can lead to cachexia, which leads to severe weight loss and muscle wasting because the body energy use rate is high and the desire to eat is low.

Conditions like cancer, COPD, and treatments through chemo can make foods unappetizing, and diseases like CKD can aggressively impact one’s digestive system.

Abnormalities in the hormonal regulation of appetite, particularly the signals of leptin and ghrelin are likely to result in alteration of appetite.

Disease Severity and Stage: At more advanced stages and especially if it is a severe case, the affected person is likely to lose his/her appetite.

Inflammatory Markers: As the appetite and the disease severity worsens, the cytokine levels are likely to be high.

Metabolic Status: Cachexia and poor nutritional status used in this study affect appetite and prognosis.

Gastrointestinal Health: Conditions such as the nauseating effect or poor digestion also will contribute to reduced appetite.

Hormonal and Neurotransmitter Levels: Hormonal abnormalities and neurotransmitters for hunger contributors are also include.

Age Group

Appetite changes could also be due to chronic diseases such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis or cystic fibrosis in children, adults, and the elderly. In this case, children may develop anorexia and may lose weight whereas, adults may develop anorexia, early satiety and may start to lose weight unintentionally. Older adults may present with many disease-related issues affecting their appetite and uptake of foods due to multiple comorbidities and age-related physiology alterations.

Control the Chronic Disease: Ensure these core disorders are well managed (e.g., cancer, chronic kidney disease) and then address symptoms such as pain, nausea, and depression to enhance appetite.

Nutritional Support: Modify the diet according to patient’s choice and provide small high-energy dense and high-protein meals and if needed appetite enhancers such as megestrol acetate or corticosteroids.

Psychosocial Support: Psychotherapy or counseling to address the psychological component, and mutual support through purposeful psychological support groups.

Medical Interventions: Promote appetite stimulating agents like cannabinoids and antidepressants; Consider tube feeding in very severe conditions where oral intake is compromised.

Monitoring and Follow-Up: Weight monitoring at least weekly and/or other anthropometric measures, nutritional history, and corresponding changes in the treatment plan.

Nutrition

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Nephrology

Nutrition

Nephrology

Nutrition

Nephrology

Nutrition

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

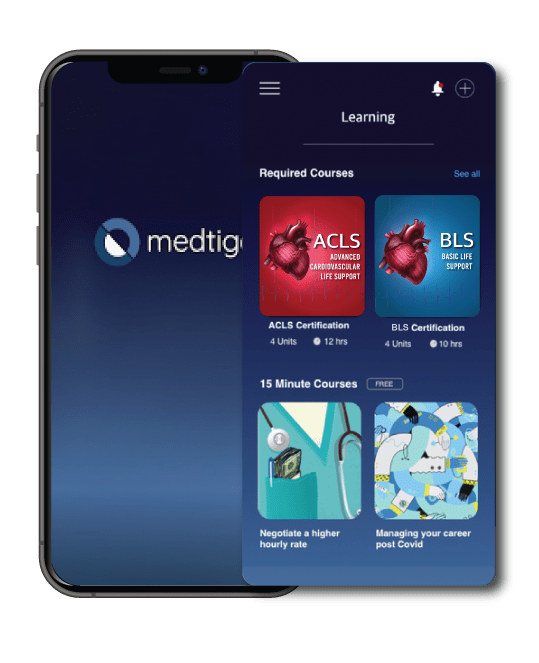

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.