Background

The Extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (E-FAST) is a rapid and bedside ultrasound technique which is sued in emergency settings. It is used to identify the potentially life-threatening injuring in trauma patients. It improves the capabilities of original focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam which was developed to detect the internal bleeding in cases of penetrating or blunt trauma to the torso.

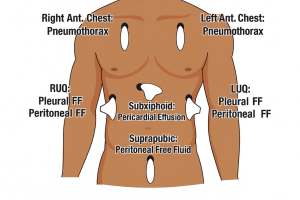

The FAST exam detects the free fluid typically considered blood in trauma cases by examining 10 anatomical structures in 4 main regions:

These locations are chosen because they are gravity-dependent, which means fluid from internal bleeding tends to collect in these spaces. Early detection of hemoperitoneum or pericardial fluid is crucial to determine the need for urgent surgical treatment or further imaging studies.

The E-FAST protocol expands beyond FAST by including scans of the anterior and lateral chest walls which enables the identification of pneumothorax and pleural fluid (hemothorax in trauma patients). This makes the E-FAST exam more effective in diagnosing injuries in both the abdominal and thoracic cavities and allows the clinicians to rapidly assess and manage critically ill patients at the bedside.

E-FAST has high sensitivity and specificity specifically in patients with low blood pressure (hypotension). It is valuable procedure because it is quick, non-invasive, safe from radiation and easily repeatable. For these reasons, it has largely taken the place of diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) in modern trauma evaluation.

A positive E-FAST result can prompt immediate procedures like chest tube insertion, pericardial drainage or emergency surgery in unstable patients. The results can help to guide the choice of additional diagnostic tests like CT scan in hemodynamically stable patients.

Although initially created for trauma care, E-FAST is also useful in non-traumatic emergencies. Its components are frequently used in the evaluation of hypotensive patients to identify causes such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy or abdominal aortic aneurysm, highlighting its broader role as a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) tool in acute care medicine.

Indications

The E-FAST exam is indicated for the rapid evaluation of patients with suspected internal injuries particularly in trauma settings or in cases of undifferentiated hypotension and shock. It is used in patients who have blunt abdominal trauma and hemodynamically unstable, those with blunt or penetrating chest injuries, regardless of their stability. This procedure plays an important role to assess the intra-abdominal bleeding, hemothorax, pneumothorax or pericardial effusion. E-FAST is also useful when a previously stable trauma patient experiences sudden clinical deterioration like hypotension or respiratory distress and the need for immediate bedside reassessment.

Beyond trauma, E-FAST is increasingly used in non-trauma situations to evaluate unexplained hypotension or shock specifically as part of the Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH) protocol. In female patients of reproductive age presenting with shock, the presence of free fluid in the pelvis may suggest a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, where E-FAST can expedite diagnosis and surgical planning.

Contraindications

The E-FAST exam is a rapid diagnostic tool with minimal risk and can be safely performed in most emergency settings. However, there are a few important considerations regarding the usage.

Absolute Contraindications: The only absolute contraindication to performing an E-FAST is when there is a clear and immediate need for time-sensitive definitive care such as emergency surgery or airway management where performing an ultrasound would delay life-saving intervention.

Relative Contraindications: There are no known relative contraindications to performing E-FAST. The procedure is non-invasive, radiation-free. It can be repeated as needed without harm. Even in patients with surgical dressings, chest tubes, or subcutaneous emphysema, a limited or modified exam may still be feasible and provide useful information.

Outcomes

Equipment

Ultrasound machine: Portable device for real-time, bedside imaging in emergency settings.

Curvilinear probe (2 to 5 MHz): Preferred probe for E-FAST and suitable for abdominal and thoracic views.

Phased-array probe (2 to 5 MHz): Optional probe useful for cardiac and intercostal views due to its small footprint.

Linear high-frequency probe (5 to 10 MHz): It is used for detailed evaluation of pleural surfaces and pneumothorax.

Ultrasound gel: It ensures proper contact and sound transmission between probe and skin.

Sterile gloves: Basic protective equipment to maintain hygiene during the scan.

Probe cover or glove: Provides a barrier to protect the probe from contamination.

Gown or disposable apron: Optional protection for the operator in high-exposure situations.

Considerations

The E-FAST exam is designed to be completed in under 5 minutes, allowing for rapid assessment in critically ill patients. Evaluation typically begins with the pericardial view, especially in cases of penetrating trauma, as pericardial fluid can cause life-threatening tamponade and must be addressed before other injuries. The procedure targets gravity dependent areas of peritoneal cavity where fluid is collected to improve the detection. Free fluid appears as black or anechoic spaces in these potential cavities on ultrasound. The scan emphasizes interfaces between solid organs which give optimal contrast to visualize even small amounts of fluid.

Patient position

The patient is lying supine in the table or in Trendelenburg position to increase the sensitivity to detect peritoneal fluid in the right upper quadrant (RUQ).

Patient Preparation

Step 1: Patient Preparation

Explain the procedure to the patient if they are conscious and able to understand. Obtain verbal consent, as the procedure is non-invasive and typically performed in urgent or emergent settings. Ensure the patient is supine on the stretcher or examination table to allow optimal visualization of fluid in gravity-dependent areas.

Expose the torso fully, including the chest and abdomen, while maintaining patient privacy and comfort as much as possible.

Step 2: Equipment Preparation

Select the appropriate probe: Use a curvilinear probe (2 to 5 MHz) as the first choice for E-FAST. A phased-array probe may also be used, especially for cardiac views.

Set up the ultrasound machine: Turn on the machine, select the abdominal or cardiac preset, and ensure appropriate depth and gain settings for clear visualization of the target structures.

Step 3: Probe Preparation

Apply ultrasound gel to the tip of the probe.

Cover the probe with a glove or probe cover, pulling it tightly to avoid air bubbles that could degrade the image.

Secure the cover with a rubber band, then apply a second layer of gel over the cover to ensure proper acoustic coupling with the patient’s skin.

Step 4: Patient Orientation

Confirm that the orientation marker on the probe corresponds with the marker dot on the ultrasound screen.

For the E-FAST exam, position the probe so that the orientation marker points to the patient’s right side. This should match the upper left corner of the ultrasound image.

Adjust monitor settings as necessary to ensure accurate left-right image orientation and optimal image quality.

Probe positions in E-FAST procedure

Step 5: Perform the E-FAST Examination

Pericardial (Cardiac) View:

The pericardial or cardiac component of the E-FAST exam primarily aims to detect hemopericardium, a potentially life-threatening complication following trauma. This view is typically obtained from the subxiphoid (subcostal) position, which allows imaging of the pericardial sac through the liver as an acoustic window.

Perihepatic [right upper quadrant (RUQ)] view:

The perihepatic or right upper quadrant (RUQ) view in the E-FAST exam is used to detect free intraperitoneal fluid and assess for hemothorax.

Pelvic (suprapubic) view:

Thoracic view:

Step 6: Documentation

After completing the E-FAST examination, it is essential to document the procedure thoroughly and ensure appropriate patient communication and follow-up. Begin by saving images of all standard anatomical views obtained during the scan, along with any additional images that depict pathological findings such as free fluid, hemothorax, or pneumothorax. These images serve as vital records for clinical decision-making and can be referenced in subsequent evaluations.

Next, inform the patient that the procedure is complete. Following this, remove and dispose of personal protective equipment (PPE) appropriately in accordance with infection control protocols, and perform hand hygiene.

Record the findings in the patient’s clinical notes, clearly stating whether the scan was positive or negative for free fluid, pneumothorax, or hemothorax, and note any limitations encountered during image acquisition. This documentation should include your interpretation of the images and any recommendation for further evaluation or management.

Based on the sonographic findings and the patient’s hemodynamic status, appropriate management should be initiated:

Diagnostic Accuracy

E-FAST has high specificality and sensitivity. For instance, in the detection of pneumothorax, E-FAST demonstrates a sensitivity of 69% and an impressive specificity of 99%, underscoring its ability to accurately rule in the condition when detected. Similarly, the test shows 91% sensitivity and 94% specificity for identifying pericardial effusion, reflecting its high diagnostic precision in cardiac injuries.

When assessing intra-abdominal free fluid, the test has a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 98%, though these numbers may fluctuate based on patient demographics and hemodynamic status. For hypotensive patients, sensitivity and specificity are 74% and 95%, respectively, while in pediatric trauma patients, the sensitivity drops slightly to 71%, with the same specificity of 95%. Such data underscore the test’s reliability, particularly for ruling out conditions due to its high specificity, but also highlight its potential for missed injuries if used in isolation.

The E-FAST exam is also favored because it can often eliminate the need for more invasive procedures like diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), and even traditional imaging like X-rays, especially in the diagnosis of pneumothorax or hemothorax. Furthermore, optimal detection of intraperitoneal fluid is often achieved by first evaluating the right paracolic gutter, a region where fluid is more likely to accumulate due to gravitational flow and fewer anatomical obstructions.

Complications

The eFAST exam is considered a safe, non-invasive diagnostic tool with no known complications.

Limitations

The E-FAST exam is a valuable bedside tool in emergency trauma care, offering rapid, non-invasive insights into internal injuries. However, despite its widespread use and life-saving potential, the E-FAST protocol is not without limitations.

One of the primary concerns with E-FAST is its limited sensitivity, especially in the early stages of trauma when the volume of intraperitoneal or intrathoracic fluid may be low. The exam typically requires at least 150 to 200 mL of free fluid to be reliably detected. In patients with smaller amounts of fluid accumulation, particularly during the initial minutes after trauma, this can result in false-negative findings. Additionally, if the hemorrhage has already clotted, the sonographic appearance may not show the typical anechoic (black) fluid but rather a mixed echogenicity, which can be missed or misinterpreted.

Conversely, false positives are another significant limitation. Pre-existing fluid collections not related to the trauma such as ascites, peritoneal dialysis fluid, ruptured ovarian cysts, or residual lavage fluid can mimic trauma-related free fluid. Similarly, a distended urinary bladder can sometimes be mistaken for intra-abdominal free fluid, especially in cases where anatomical landmarks are obscured.

E-FAST also has technical and anatomical limitations. It cannot assess retroperitoneal bleeding and is unable to differentiate between blood and urine in cases of severe pelvic trauma. Moreover, bowel gas, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, or pneumomediastinum can hinder ultrasound image acquisition and interpretation. In obese patients or those with atypical anatomy, visualization of key structures may be suboptimal.

Crucially, the accuracy and utility of E-FAST are highly dependent on the operator’s skill and experience. Inconsistencies in technique and interpretation between providers can lead to misdiagnoses, especially when multiple clinicians perform serial scans. The subjective nature of image interpretation underscores the need for comprehensive training and regular proficiency assessments in point-of-care ultrasound.

The Extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (E-FAST) is a rapid and bedside ultrasound technique which is sued in emergency settings. It is used to identify the potentially life-threatening injuring in trauma patients. It improves the capabilities of original focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam which was developed to detect the internal bleeding in cases of penetrating or blunt trauma to the torso.

The FAST exam detects the free fluid typically considered blood in trauma cases by examining 10 anatomical structures in 4 main regions:

These locations are chosen because they are gravity-dependent, which means fluid from internal bleeding tends to collect in these spaces. Early detection of hemoperitoneum or pericardial fluid is crucial to determine the need for urgent surgical treatment or further imaging studies.

The E-FAST protocol expands beyond FAST by including scans of the anterior and lateral chest walls which enables the identification of pneumothorax and pleural fluid (hemothorax in trauma patients). This makes the E-FAST exam more effective in diagnosing injuries in both the abdominal and thoracic cavities and allows the clinicians to rapidly assess and manage critically ill patients at the bedside.

E-FAST has high sensitivity and specificity specifically in patients with low blood pressure (hypotension). It is valuable procedure because it is quick, non-invasive, safe from radiation and easily repeatable. For these reasons, it has largely taken the place of diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) in modern trauma evaluation.

A positive E-FAST result can prompt immediate procedures like chest tube insertion, pericardial drainage or emergency surgery in unstable patients. The results can help to guide the choice of additional diagnostic tests like CT scan in hemodynamically stable patients.

Although initially created for trauma care, E-FAST is also useful in non-traumatic emergencies. Its components are frequently used in the evaluation of hypotensive patients to identify causes such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy or abdominal aortic aneurysm, highlighting its broader role as a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) tool in acute care medicine.

The E-FAST exam is indicated for the rapid evaluation of patients with suspected internal injuries particularly in trauma settings or in cases of undifferentiated hypotension and shock. It is used in patients who have blunt abdominal trauma and hemodynamically unstable, those with blunt or penetrating chest injuries, regardless of their stability. This procedure plays an important role to assess the intra-abdominal bleeding, hemothorax, pneumothorax or pericardial effusion. E-FAST is also useful when a previously stable trauma patient experiences sudden clinical deterioration like hypotension or respiratory distress and the need for immediate bedside reassessment.

Beyond trauma, E-FAST is increasingly used in non-trauma situations to evaluate unexplained hypotension or shock specifically as part of the Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension (RUSH) protocol. In female patients of reproductive age presenting with shock, the presence of free fluid in the pelvis may suggest a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, where E-FAST can expedite diagnosis and surgical planning.

The E-FAST exam is a rapid diagnostic tool with minimal risk and can be safely performed in most emergency settings. However, there are a few important considerations regarding the usage.

Absolute Contraindications: The only absolute contraindication to performing an E-FAST is when there is a clear and immediate need for time-sensitive definitive care such as emergency surgery or airway management where performing an ultrasound would delay life-saving intervention.

Relative Contraindications: There are no known relative contraindications to performing E-FAST. The procedure is non-invasive, radiation-free. It can be repeated as needed without harm. Even in patients with surgical dressings, chest tubes, or subcutaneous emphysema, a limited or modified exam may still be feasible and provide useful information.

Ultrasound machine: Portable device for real-time, bedside imaging in emergency settings.

Curvilinear probe (2 to 5 MHz): Preferred probe for E-FAST and suitable for abdominal and thoracic views.

Phased-array probe (2 to 5 MHz): Optional probe useful for cardiac and intercostal views due to its small footprint.

Linear high-frequency probe (5 to 10 MHz): It is used for detailed evaluation of pleural surfaces and pneumothorax.

Ultrasound gel: It ensures proper contact and sound transmission between probe and skin.

Sterile gloves: Basic protective equipment to maintain hygiene during the scan.

Probe cover or glove: Provides a barrier to protect the probe from contamination.

Gown or disposable apron: Optional protection for the operator in high-exposure situations.

Considerations

The E-FAST exam is designed to be completed in under 5 minutes, allowing for rapid assessment in critically ill patients. Evaluation typically begins with the pericardial view, especially in cases of penetrating trauma, as pericardial fluid can cause life-threatening tamponade and must be addressed before other injuries. The procedure targets gravity dependent areas of peritoneal cavity where fluid is collected to improve the detection. Free fluid appears as black or anechoic spaces in these potential cavities on ultrasound. The scan emphasizes interfaces between solid organs which give optimal contrast to visualize even small amounts of fluid.

The patient is lying supine in the table or in Trendelenburg position to increase the sensitivity to detect peritoneal fluid in the right upper quadrant (RUQ).

Step 1: Patient Preparation

Explain the procedure to the patient if they are conscious and able to understand. Obtain verbal consent, as the procedure is non-invasive and typically performed in urgent or emergent settings. Ensure the patient is supine on the stretcher or examination table to allow optimal visualization of fluid in gravity-dependent areas.

Expose the torso fully, including the chest and abdomen, while maintaining patient privacy and comfort as much as possible.

Step 2: Equipment Preparation

Select the appropriate probe: Use a curvilinear probe (2 to 5 MHz) as the first choice for E-FAST. A phased-array probe may also be used, especially for cardiac views.

Set up the ultrasound machine: Turn on the machine, select the abdominal or cardiac preset, and ensure appropriate depth and gain settings for clear visualization of the target structures.

Step 3: Probe Preparation

Apply ultrasound gel to the tip of the probe.

Cover the probe with a glove or probe cover, pulling it tightly to avoid air bubbles that could degrade the image.

Secure the cover with a rubber band, then apply a second layer of gel over the cover to ensure proper acoustic coupling with the patient’s skin.

Step 4: Patient Orientation

Confirm that the orientation marker on the probe corresponds with the marker dot on the ultrasound screen.

For the E-FAST exam, position the probe so that the orientation marker points to the patient’s right side. This should match the upper left corner of the ultrasound image.

Adjust monitor settings as necessary to ensure accurate left-right image orientation and optimal image quality.

Probe positions in E-FAST procedure

Step 5: Perform the E-FAST Examination

Pericardial (Cardiac) View:

The pericardial or cardiac component of the E-FAST exam primarily aims to detect hemopericardium, a potentially life-threatening complication following trauma. This view is typically obtained from the subxiphoid (subcostal) position, which allows imaging of the pericardial sac through the liver as an acoustic window.

Perihepatic [right upper quadrant (RUQ)] view:

The perihepatic or right upper quadrant (RUQ) view in the E-FAST exam is used to detect free intraperitoneal fluid and assess for hemothorax.

Pelvic (suprapubic) view:

Thoracic view:

Step 6: Documentation

After completing the E-FAST examination, it is essential to document the procedure thoroughly and ensure appropriate patient communication and follow-up. Begin by saving images of all standard anatomical views obtained during the scan, along with any additional images that depict pathological findings such as free fluid, hemothorax, or pneumothorax. These images serve as vital records for clinical decision-making and can be referenced in subsequent evaluations.

Next, inform the patient that the procedure is complete. Following this, remove and dispose of personal protective equipment (PPE) appropriately in accordance with infection control protocols, and perform hand hygiene.

Record the findings in the patient’s clinical notes, clearly stating whether the scan was positive or negative for free fluid, pneumothorax, or hemothorax, and note any limitations encountered during image acquisition. This documentation should include your interpretation of the images and any recommendation for further evaluation or management.

Based on the sonographic findings and the patient’s hemodynamic status, appropriate management should be initiated:

Diagnostic Accuracy

E-FAST has high specificality and sensitivity. For instance, in the detection of pneumothorax, E-FAST demonstrates a sensitivity of 69% and an impressive specificity of 99%, underscoring its ability to accurately rule in the condition when detected. Similarly, the test shows 91% sensitivity and 94% specificity for identifying pericardial effusion, reflecting its high diagnostic precision in cardiac injuries.

When assessing intra-abdominal free fluid, the test has a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 98%, though these numbers may fluctuate based on patient demographics and hemodynamic status. For hypotensive patients, sensitivity and specificity are 74% and 95%, respectively, while in pediatric trauma patients, the sensitivity drops slightly to 71%, with the same specificity of 95%. Such data underscore the test’s reliability, particularly for ruling out conditions due to its high specificity, but also highlight its potential for missed injuries if used in isolation.

The E-FAST exam is also favored because it can often eliminate the need for more invasive procedures like diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL), and even traditional imaging like X-rays, especially in the diagnosis of pneumothorax or hemothorax. Furthermore, optimal detection of intraperitoneal fluid is often achieved by first evaluating the right paracolic gutter, a region where fluid is more likely to accumulate due to gravitational flow and fewer anatomical obstructions.

Complications

The eFAST exam is considered a safe, non-invasive diagnostic tool with no known complications.

Limitations

The E-FAST exam is a valuable bedside tool in emergency trauma care, offering rapid, non-invasive insights into internal injuries. However, despite its widespread use and life-saving potential, the E-FAST protocol is not without limitations.

One of the primary concerns with E-FAST is its limited sensitivity, especially in the early stages of trauma when the volume of intraperitoneal or intrathoracic fluid may be low. The exam typically requires at least 150 to 200 mL of free fluid to be reliably detected. In patients with smaller amounts of fluid accumulation, particularly during the initial minutes after trauma, this can result in false-negative findings. Additionally, if the hemorrhage has already clotted, the sonographic appearance may not show the typical anechoic (black) fluid but rather a mixed echogenicity, which can be missed or misinterpreted.

Conversely, false positives are another significant limitation. Pre-existing fluid collections not related to the trauma such as ascites, peritoneal dialysis fluid, ruptured ovarian cysts, or residual lavage fluid can mimic trauma-related free fluid. Similarly, a distended urinary bladder can sometimes be mistaken for intra-abdominal free fluid, especially in cases where anatomical landmarks are obscured.

E-FAST also has technical and anatomical limitations. It cannot assess retroperitoneal bleeding and is unable to differentiate between blood and urine in cases of severe pelvic trauma. Moreover, bowel gas, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, or pneumomediastinum can hinder ultrasound image acquisition and interpretation. In obese patients or those with atypical anatomy, visualization of key structures may be suboptimal.

Crucially, the accuracy and utility of E-FAST are highly dependent on the operator’s skill and experience. Inconsistencies in technique and interpretation between providers can lead to misdiagnoses, especially when multiple clinicians perform serial scans. The subjective nature of image interpretation underscores the need for comprehensive training and regular proficiency assessments in point-of-care ultrasound.

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

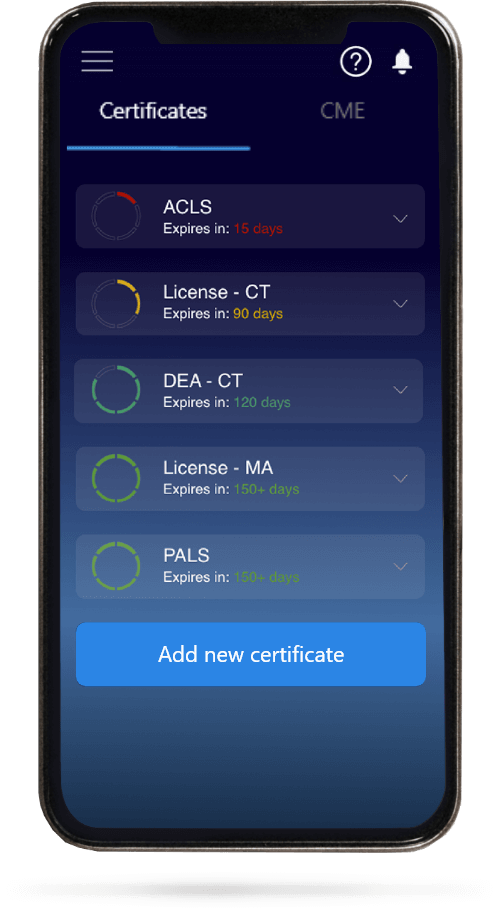

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.