Background

Intestinal fistulas refer to the condition whereby the bowel is joined in an improper manner to other areas of the bowel or any other structures like the skin, bladder, or other parts of the GI tract. They may be associated with surgical complications like inflammation, Crohn’s disease, infections, traumas, malignancies, radiation therapy, and many others. Consequently, intestinal fistulas can be associated with several complications, such as malnutrition, septicemia, electrolyte imbalance, and prolongation of the duration of hospitalization.

Indications

Failure of Conservative Management: When simple measures, including nutritional support, infection control, and wound care with one to two stitches, do not achieve fistula closure after a fair amount of time, usually 4-6 weeks.

High-output Fistulas: These fistulas develop large effusion rates that cause complications involving fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional imbalances and thus should not be managed conservatively.

Sepsis or Infection: Untreated, uncontrolled sepsis, newly formed uncontrolled abscessation, or local infection in a fistula originating, which cannot be sufficiently addressed by antibiotics or drainage.

Erosion into Adjacent Organs: Fistulas where they themselves invade other structures such as the bladder, vagina, or indeed the skin leading to complications such as contamination with urine or fecal matter.

Obstruction or Stricture: This is usually associated with a fistula being complicated by bowel obstruction or bowel stricture, which cannot be treated non-operatively.

Malignancy: When cancer is present at this fistula site, then surgery is inevitable.

Failure to Heal: Long-tract fistulas that do not heal on their own and fail to close even with the use of conservative management, which may take about three to six months.

Contraindications

Severe Malnutrition: This is because patients who have poor nutrition may not be able to undergo surgery well, and in case they do, they may take a long time for their wounds to heal.

Uncontrolled Systemic Infections: If a patient has a severe case of septicemia, the infection could either be made worse by surgery or even spread throughout the body.

Uncontrolled Diabetes Mellitus: Diabetes, if not well managed, causes poor wound healing, and a series of complications occur after surgery.

Severe Cardiac or Respiratory Conditions: It may also be seen that patients who are having severe cardiac or pulmonary problems are at a higher risk during the surgery.

Uncorrected Coagulation Disorders: Disorders of coagulation have the risk of post and intraoperative hemorrhage.

Inoperable Fistula: In some cases, the fistula may be in a location that makes surgical repair very difficult or impossible.

Recent Surgery or Radiation: They include the location of abnormal cells because, if the area has just undergone surgery or radiation, it could be that the area is not suitable for further surgery.

Outcomes

Equipment

Surgical Instruments:

Hemostats

Needle Holder

Scissors

Scalpel

Sutures and Staplers:

Staplers

Absorbable Sutures

Staplers

Surgical Drains:

Penrose Drain

Jackson-Pratt (JP) Drain

Endoscopy Equipment:

Endoscope

Laparoscope

Electrocautery Device:

Surgical Suction Device:

Protective Equipment:

Surgical Drapes

Sterile Gloves and Gowns

Patient Preparation:

Assessment and Evaluation:

Medical History: Check all the surgical procedures made in the patient’s history, illnesses concurrent with the patient, and prescribed medications.

Physical Examination: Consider the size, extent, location, and nature of the fistula. Assess the patient’s nutritional reserves and the presence of any other complications that may be observed.

Nutritional Optimization:

Dietary Adjustments: Patients with a fistula may require dietary adjustments based on the location or extent of the fistula and the amount of output required for enteral nutrition support or total parenteral nutrition.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: Ensure the body is adequately supplied with proper fluids.

Bowel Preparation:

Cleansing: Some of them may require the patients to take a pre-procedure bowel lavage using laxatives or enemas with the intention of lowering bowel content.

Infection Control:

Antibiotics: Give the recommended prophylactic antibiotics as advised by the contributing surgical specialists.

Hygiene: Do prepare the skin and the specific site for surgery correctly.

Preoperative Testing:

Laboratory Tests: Basic investigations: complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte profile, liver and kidney function tests, and any other tests based on history and examination.

Imaging Studies: In some instances, further imaging such as CT scans, ultrasound, and an MRI might be necessary to better view the fistula and the adjacent structures.

Consent:

Informed Consent: They should be given informed consent after explaining the risks, the benefits, and other available options rather than the surgery.

Patient position:

In the surgery of intestinal fistulas, the positioning of patients is essential to get the best access to operations as well as to reduce complications. Usually, the patient is in a supine position on the operating table.

Preoperative Preparation

Assessment and Stabilization: Assess the general health, nutritional status of the patient, in addition to the features of the fistula (size, location, amount of output). Make the patient comfortable, monitor and correct electrolyte abnormalities, and observe the patient’s dietary intake.

Imaging Studies: Incorporate imaging modalities like CT scans or MRI to determine the anatomical structures involved or any adjacent structures involved in the fistula.

Surgical Planning: Schedule how the fistula shall be approached depending on where it is situated and the patient’s health condition. Choose primary closure or resection with anastomosis or other methods.

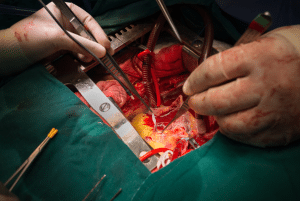

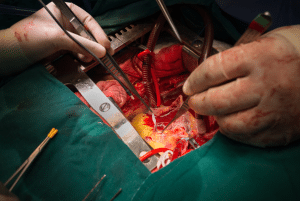

Step 2-Surgical Technique:

Anesthesia: General anesthesia is preferred for the patient.

Positioning: Supine or in a lateral position, the patient must be well positioned for easy access to the fistula to be addressed. This is usually done lying down, although this depends on the location of the fistula.

Incision: Make a correct incision around the fistula. The incision should be adequate to have a clear field of view of the fistula plus the skin and subcutaneous tissues involved.

Dissection: Dissecting the surrounding tissues of the fistula. Locate the fistulous track and distinguish it from bowel loops, organs, or blood vessels.

Identification of Fistula: It is necessary to define the sites of the internal and the external fistula. In some cases, this step requires a meticulous dissection to identify the fistulous tract and follow it to its source.

Resection: Resect the segment of the bowel; depending on the characteristics of the fistula, resection of an affected segment of the bowel may be required. If the fistula is associated with other diseases, such as Crohn’s or cancer, then more tissue may be required to be excised.

Closure of Fistula: Surgically, one would need to de-roof the fistula, therefore sealing both internal and external holes.

Techniques may include:

Primary Closure: If you are healing the fistula tract and the surrounding tissue is healthy, suture the fistula tract directly.

Omental Flap: To cover the fistula site and improve the healing process, the surgeon can use an omentum.

Tissue Interposition: Closing the opening of the fistula with the adjacent soft tissue.

Anastomosis: If bowel resection is done, then anastomosis will be made to join the two ends to bypass the defective segment. This may, therefore, be an end-to-end anastomosis, end-to-side anastomosis, and side-to-side anastomosis, depending on the resected bowel segments.

Drain Placement: Locate drains if necessary for control of postoperative collections or infection-related problems.

Wound Closure: Close the incision in layers. Ensure proper alignment of the abdominal wall layers to reduce the risk of complications.

Step 3-Postoperative Care:

Monitoring: Monitor the patient for any complications like infection, leakage, or bowel obstruction.

Nutritional Support: Give nutritional supplementation where required, which would entail being parenteral in the initial stages if the bowel is dysfunctional.

Wound Care: Care for the surgical site and any drains according to standard protocols.

Follow-Up: Recommend that patients make subsequent appointments to check for the fistula healing status and for recurrence.

Complications

Infection: Infection that develops at the site of surgery or within the peritoneal cavity after the surgery had been performed.

Wound Dehiscence: Surgical site infection which leads to the reopening of the developmental surgical wound also take more time to heal and besides may necessitate another operation.

Leakage: Some of the consequences of leakage of intestinal content from the fistula site may include peritonitis or any other severe condition.

Stricture or Obstruction: The formation of adhesion which brings about intestinal obstruction where the intestines are already narrowed at site of surgery.

Fistula Recurrence: Fistula recurrence is another complication that patients may develop or they may experience new fistulas.

Nutritional Deficiencies: All these may result into alteration of the absorption or over secretion of the digestive fluids which leads to malnutrition or low levels of electrolytes.

Delayed Wound Healing: Most commonly in patients with some conditions and/or nutritional deficiencies.

Intestinal fistulas refer to the condition whereby the bowel is joined in an improper manner to other areas of the bowel or any other structures like the skin, bladder, or other parts of the GI tract. They may be associated with surgical complications like inflammation, Crohn’s disease, infections, traumas, malignancies, radiation therapy, and many others. Consequently, intestinal fistulas can be associated with several complications, such as malnutrition, septicemia, electrolyte imbalance, and prolongation of the duration of hospitalization.

Failure of Conservative Management: When simple measures, including nutritional support, infection control, and wound care with one to two stitches, do not achieve fistula closure after a fair amount of time, usually 4-6 weeks.

High-output Fistulas: These fistulas develop large effusion rates that cause complications involving fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional imbalances and thus should not be managed conservatively.

Sepsis or Infection: Untreated, uncontrolled sepsis, newly formed uncontrolled abscessation, or local infection in a fistula originating, which cannot be sufficiently addressed by antibiotics or drainage.

Erosion into Adjacent Organs: Fistulas where they themselves invade other structures such as the bladder, vagina, or indeed the skin leading to complications such as contamination with urine or fecal matter.

Obstruction or Stricture: This is usually associated with a fistula being complicated by bowel obstruction or bowel stricture, which cannot be treated non-operatively.

Malignancy: When cancer is present at this fistula site, then surgery is inevitable.

Failure to Heal: Long-tract fistulas that do not heal on their own and fail to close even with the use of conservative management, which may take about three to six months.

Severe Malnutrition: This is because patients who have poor nutrition may not be able to undergo surgery well, and in case they do, they may take a long time for their wounds to heal.

Uncontrolled Systemic Infections: If a patient has a severe case of septicemia, the infection could either be made worse by surgery or even spread throughout the body.

Uncontrolled Diabetes Mellitus: Diabetes, if not well managed, causes poor wound healing, and a series of complications occur after surgery.

Severe Cardiac or Respiratory Conditions: It may also be seen that patients who are having severe cardiac or pulmonary problems are at a higher risk during the surgery.

Uncorrected Coagulation Disorders: Disorders of coagulation have the risk of post and intraoperative hemorrhage.

Inoperable Fistula: In some cases, the fistula may be in a location that makes surgical repair very difficult or impossible.

Recent Surgery or Radiation: They include the location of abnormal cells because, if the area has just undergone surgery or radiation, it could be that the area is not suitable for further surgery.

Surgical Instruments:

Hemostats

Needle Holder

Scissors

Scalpel

Sutures and Staplers:

Staplers

Absorbable Sutures

Staplers

Surgical Drains:

Penrose Drain

Jackson-Pratt (JP) Drain

Endoscopy Equipment:

Endoscope

Laparoscope

Electrocautery Device:

Surgical Suction Device:

Protective Equipment:

Surgical Drapes

Sterile Gloves and Gowns

Patient Preparation:

Assessment and Evaluation:

Medical History: Check all the surgical procedures made in the patient’s history, illnesses concurrent with the patient, and prescribed medications.

Physical Examination: Consider the size, extent, location, and nature of the fistula. Assess the patient’s nutritional reserves and the presence of any other complications that may be observed.

Nutritional Optimization:

Dietary Adjustments: Patients with a fistula may require dietary adjustments based on the location or extent of the fistula and the amount of output required for enteral nutrition support or total parenteral nutrition.

Fluid and Electrolyte Balance: Ensure the body is adequately supplied with proper fluids.

Bowel Preparation:

Cleansing: Some of them may require the patients to take a pre-procedure bowel lavage using laxatives or enemas with the intention of lowering bowel content.

Infection Control:

Antibiotics: Give the recommended prophylactic antibiotics as advised by the contributing surgical specialists.

Hygiene: Do prepare the skin and the specific site for surgery correctly.

Preoperative Testing:

Laboratory Tests: Basic investigations: complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte profile, liver and kidney function tests, and any other tests based on history and examination.

Imaging Studies: In some instances, further imaging such as CT scans, ultrasound, and an MRI might be necessary to better view the fistula and the adjacent structures.

Consent:

Informed Consent: They should be given informed consent after explaining the risks, the benefits, and other available options rather than the surgery.

Patient position:

In the surgery of intestinal fistulas, the positioning of patients is essential to get the best access to operations as well as to reduce complications. Usually, the patient is in a supine position on the operating table.

Assessment and Stabilization: Assess the general health, nutritional status of the patient, in addition to the features of the fistula (size, location, amount of output). Make the patient comfortable, monitor and correct electrolyte abnormalities, and observe the patient’s dietary intake.

Imaging Studies: Incorporate imaging modalities like CT scans or MRI to determine the anatomical structures involved or any adjacent structures involved in the fistula.

Surgical Planning: Schedule how the fistula shall be approached depending on where it is situated and the patient’s health condition. Choose primary closure or resection with anastomosis or other methods.

Step 2-Surgical Technique:

Anesthesia: General anesthesia is preferred for the patient.

Positioning: Supine or in a lateral position, the patient must be well positioned for easy access to the fistula to be addressed. This is usually done lying down, although this depends on the location of the fistula.

Incision: Make a correct incision around the fistula. The incision should be adequate to have a clear field of view of the fistula plus the skin and subcutaneous tissues involved.

Dissection: Dissecting the surrounding tissues of the fistula. Locate the fistulous track and distinguish it from bowel loops, organs, or blood vessels.

Identification of Fistula: It is necessary to define the sites of the internal and the external fistula. In some cases, this step requires a meticulous dissection to identify the fistulous tract and follow it to its source.

Resection: Resect the segment of the bowel; depending on the characteristics of the fistula, resection of an affected segment of the bowel may be required. If the fistula is associated with other diseases, such as Crohn’s or cancer, then more tissue may be required to be excised.

Closure of Fistula: Surgically, one would need to de-roof the fistula, therefore sealing both internal and external holes.

Techniques may include:

Primary Closure: If you are healing the fistula tract and the surrounding tissue is healthy, suture the fistula tract directly.

Omental Flap: To cover the fistula site and improve the healing process, the surgeon can use an omentum.

Tissue Interposition: Closing the opening of the fistula with the adjacent soft tissue.

Anastomosis: If bowel resection is done, then anastomosis will be made to join the two ends to bypass the defective segment. This may, therefore, be an end-to-end anastomosis, end-to-side anastomosis, and side-to-side anastomosis, depending on the resected bowel segments.

Drain Placement: Locate drains if necessary for control of postoperative collections or infection-related problems.

Wound Closure: Close the incision in layers. Ensure proper alignment of the abdominal wall layers to reduce the risk of complications.

Step 3-Postoperative Care:

Monitoring: Monitor the patient for any complications like infection, leakage, or bowel obstruction.

Nutritional Support: Give nutritional supplementation where required, which would entail being parenteral in the initial stages if the bowel is dysfunctional.

Wound Care: Care for the surgical site and any drains according to standard protocols.

Follow-Up: Recommend that patients make subsequent appointments to check for the fistula healing status and for recurrence.

Complications

Infection: Infection that develops at the site of surgery or within the peritoneal cavity after the surgery had been performed.

Wound Dehiscence: Surgical site infection which leads to the reopening of the developmental surgical wound also take more time to heal and besides may necessitate another operation.

Leakage: Some of the consequences of leakage of intestinal content from the fistula site may include peritonitis or any other severe condition.

Stricture or Obstruction: The formation of adhesion which brings about intestinal obstruction where the intestines are already narrowed at site of surgery.

Fistula Recurrence: Fistula recurrence is another complication that patients may develop or they may experience new fistulas.

Nutritional Deficiencies: All these may result into alteration of the absorption or over secretion of the digestive fluids which leads to malnutrition or low levels of electrolytes.

Delayed Wound Healing: Most commonly in patients with some conditions and/or nutritional deficiencies.

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.