Background

A renal biopsy is an essential diagnostic procedure that involves collecting kidney tissue samples for microscopic analysis to assess various kidney diseases. It helps diagnose both specific problems in one part of the kidney (like a lump or tumor) and widespread issues that affect kidney function (like diseases or medication side effects).

There are two main types of kidney biopsies:

Targeted biopsies, which check a specific mass or lump to see if it might be cancer.

Non-targeted biopsies, which take a small sample of kidney tissue (usually from the outer part, called the cortex) to look for diseases that affect the whole kidney, such as transplant rejection, side effects from medications, diabetes, or other long-term conditions.

There are different ways to perform a kidney biopsy:

Percutaneous biopsy (most common): Done using a needle through the skin, guided by imaging.

Transvenous biopsy: Done through a vein.

Laparoscopic biopsy: Done using small surgical tools through tiny cuts in the belly.

Open surgical biopsy: Done through a larger surgery.

Anatomy and physiology

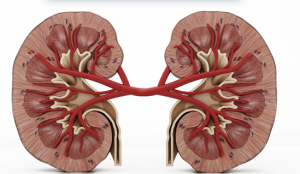

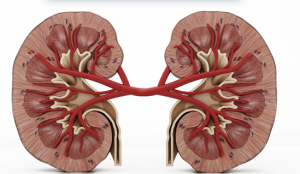

Human kidneys

The normal (non-transplant) kidney site in the retroperitoneal space, which is behind the lining of the abdominal cavity. When doing a kidney biopsy, it’s best to keep the needle in this space to avoid hitting other organs and causing complications.

For non-targeted biopsies, doctors usually take tissue from the renal cortex- the outer part of the kidney. That’s because the cortex contains most of the important structures needed to diagnose kidney diseases, including:

Glomeruli (where blood is filtered)

Bowman’s space

Small arteries and arterioles

Proximal and distal tubules

Early collecting ducts

The renal medulla, or inner part of the kidney, doesn’t have glomeruli. It mostly contains loops of Henle and parts of the tubules. So, sampling the medulla isn’t usually necessary, except in rare cases like:

Suspected tumors

Nephronophthisis (a rare condition with cysts at the edge of the cortex and medulla)

Medullary cystic kidney disease (though this is usually diagnosed with imaging, not biopsy)

The blood supply to the kidney generally starts from a single renal artery that splits into front (anterior) and back (posterior) branches. These arteries are “end arteries,” they don’t overlap in the areas they supply. The zone where the front and back blood supplies meet along the back side of the kidney (called Hyrtl’s or Brodel’s line) is thought to be the safest place to take a tissue sample, because it has fewer blood vessels. However, this area doesn’t show up on imaging, so the doctor must estimate where it is.

Before the biopsy, imaging tests like ultrasound, CT, or MRI are done to help plan the safest path for the needle. It’s important to remember that not everyone has “typical” kidney anatomy, some people have kidneys in unusual positions (like ectopic or horseshoe kidneys), and that may change how the procedure is done.

Indications

Unexplained Kidney Problems

Persistent hematuria (especially with proteinuria)

Nephrotic syndrome or significant proteinuria >1 g/day

Acute kidney injury (AKI) of unknown cause

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) of unclear etiology

Suspected Specific Renal Diseases

Glomerulonephritis (e.g., lupus nephritis, IgA nephropathy)

Systemic diseases with renal involvement (e.g., SLE, vasculitis, amyloidosis)

Tubulointerstitial diseases, when diagnosis is uncertain

Transplant-Related Indications

Monitoring allograft function

Unexplained rise in serum creatinine

Suspected rejection

Drug toxicity

Recurrent or de novo glomerular disease

Treatment Planning or Prognosis

To guide therapy decisions (e.g., immunosuppressive treatment)

To assess prognosis in progressive or suspected irreversible kidney disease

Contraindications

According to the 2016 guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA), kidney tumor biopsies are generally not recommended in certain situations:

Young, healthy individuals who prefer not to deal with the uncertainties that come with biopsy results.

Older patients who would be managed without surgery or invasive treatment, no matter what the biopsy shows.

There are also several imaging-related scenarios where a biopsy may not be helpful or could be risky:

Bleeding or protein inside a complex cyst: On ultrasound, CT, or MRI, dense fluid from bleeding or protein can look like a solid mass. Comparing scans before and after contrast, or using contrast-subtraction techniques, can help sort this out.

Pseudoenhancement: This refers to a false appearance of increased brightness or density on post-contrast scans, typically affecting small (<2 cm) soft lesions next to normal kidney tissue. These can mimic solid tumors but may not be true growths. In such cases, simply watching the lesion over time may be appropriate.

Lesions that brighten like blood vessels: If a mass lights up to the same degree as the blood vessels (like the aorta) on contrast-enhanced scans, it could be a vascular abnormality (e.g., a pseudoaneurysm) rather than a tumor. Additional testing with contrast-enhanced ultrasound or specialized MRI may be a better next step.

In these cases-such as suspected blood/protein-filled cysts or pseudoenhancement-biopsies often fail to provide useful results. For vascular lesions, biopsy carries a significant risk of bleeding and should be avoided unless necessary.

Imaging Features That Suggest a Benign Tumor

Visible fat in the mass: This is typical of a benign angiomyolipoma, especially if there are no signs of calcification or aggressive growth.

Minimal (microscopic) fat: Some angiomyolipomas don’t have visible fat but still contain small amounts inside the cells. These can look like cancer on imaging:

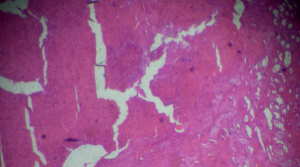

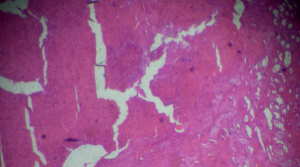

Kidney adenocarcinoma biopsy under light microscopy

Like papillary renal cell carcinoma, they appear dark on T2-weighted MRI.

Like clear cell carcinoma, they show strong contrast enhancement.

If both features are present, it’s more likely to be a fat-poor angiomyolipoma, not cancer.

Fast-growing, poorly defined mass in someone with a urinary tract infection: This may point to localized kidney infection (focal pyelonephritis). If the mass doesn’t go away after the infection is treated, a biopsy may be needed to check if it’s an infection or a tumor.

Outcomes

Equipment

Imaging Equipment

Ultrasound machine

CT scanner

MRI (rarely used)

Biopsy Needles

Core biopsy needle (automated or semi-automated)

Gauge size typically ranges from 14G to 18G

Local Anesthesia

Sterile Procedure Supplies

Needle Guide/Holder

Collection Containers

Emergency Supplies

Post-Biopsy Monitoring Equipment

Patient Preparation:

The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends that patients be clearly informed about why a biopsy is being done, what the test results might mean (both good and bad), the possible risks, and the chance that the test won’t give a clear answer.

The doctor who recommends the biopsy usually a urologist or nephrologist should go over all of this with the patient before scheduling the procedure.

If the patient learns about the risks for the first time during the consent process and then decides to wait until they can talk to the referring doctor again, that decision should be respected.

Patients should also be informed about how they will be positioned during the procedure (usually lying face down or slightly to the side) and what type of pain management or medication will be used.

For hard-to-reach areas, it helps to plan the biopsy using both ultrasound and CT scans. Each has its advantages: ultrasound is quick, while CT provides clearer images of soft tissues.

Some CT-guided biopsies, particularly those targeting the upper part of the kidney, may require special techniques such as adjusting the CT scanner angle or performing calculations to determine the correct needle trajectory. To find the appropriate angle, divide the depth of the lesion by the distance from the skin surface, then use a calculator to determine the inverse tangent (arctangent) of that number, which gives the angle in degrees.

Patient position:

Prone Position

The patient lies flat on their stomach.

This is the standard position for posterior (back side) kidney access, especially for lower or mid-pole kidney lesions.

Prone Oblique Position

The patient lies on their stomach but slightly turned to one side (usually about 30 degrees).

This can improve access and comfort, especially if the target area is slightly lateral (toward the side) or if full prone is uncomfortable.

Technique

Step 1-Pre-Procedure Preparation:

Confirm indication for biopsy and review imaging to locate the kidney.

Check lab work (especially coagulation tests and platelet count).

Obtain informed consent after discussing risks and benefits with the patient.

Ensure the patient has arranged transportation home and has someone available to monitor them after the procedure.

Step 2-Position the Patient:

Prone position (lying on the stomach) is most common.

Use pillows under the abdomen for comfort and better access.

In special cases (e.g., transplant kidney), supine (on the back) may be used.

Step3-Site Localization

Use ultrasound or CT to identify the kidney and plan the biopsy path.

Typically, the lower pole of the kidney is chosen to reduce the risk of hitting large blood vessels.

Step 4-Skin Preparation and Anesthesia

Clean the skin with antiseptic.

Drape the area to maintain a sterile field.

Inject local anesthetic into the skin and deeper tissue down to the kidney capsule.

Step 5-Needle Insertion

Use image guidance to insert the biopsy needle (usually 18-gauge or smaller).

Confirm the needle is in the right position before taking samples.

Obtain 1-3 core tissue samples, depending on the quality and amount needed.

Step 6-Post-Biopsy Care

Apply pressure to the biopsy site and place a sterile bandage.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, urine color, and pain level for several hours.

Perform a follow-up ultrasound if there’s concern for bleeding or complications.

Discharge instructions include no heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 24-48 hours.

According to the 2013 practice guidelines from the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), the risk of serious bleeding that requires a blood transfusion is expected to be less than 3% when using an 18-gauge needle or smaller. If the rate goes over 5%, it may be a sign that the procedure technique or patient selection needs to be reviewed and improved. The guidelines also mention that larger needles might slightly increase the risk of complications, but they don’t go into detail about those risks.

The following complication rates were reported:

In real-world practice, minor vascular injuries that don’t need treatment are thought to be much more common than reported in studies, especially since most studies don’t routinely use ultrasound after the biopsy to check for these injuries.

Although not mentioned in the SIR guidelines or Patel’s study, another experienced clinician found that arteriovenous fistulas (abnormal connections between arteries and veins) that needed treatment happened in about 1% of kidney biopsies. These fistulas are seen more often when doctors actively look for them using ultrasound after the procedure.

In fact, almost every patient ends up with some bleeding around the kidney (perirenal hematoma), which is easier to detect on CT or MRI than on ultrasound.

In rare but serious cases, a patient may lose a kidney due to complications. Deaths have also occurred, though they are extremely rare, following severe bleeding or other serious issues after a kidney biopsy.

References

References

A renal biopsy is an essential diagnostic procedure that involves collecting kidney tissue samples for microscopic analysis to assess various kidney diseases. It helps diagnose both specific problems in one part of the kidney (like a lump or tumor) and widespread issues that affect kidney function (like diseases or medication side effects).

There are two main types of kidney biopsies:

Targeted biopsies, which check a specific mass or lump to see if it might be cancer.

Non-targeted biopsies, which take a small sample of kidney tissue (usually from the outer part, called the cortex) to look for diseases that affect the whole kidney, such as transplant rejection, side effects from medications, diabetes, or other long-term conditions.

There are different ways to perform a kidney biopsy:

Percutaneous biopsy (most common): Done using a needle through the skin, guided by imaging.

Transvenous biopsy: Done through a vein.

Laparoscopic biopsy: Done using small surgical tools through tiny cuts in the belly.

Open surgical biopsy: Done through a larger surgery.

Anatomy and physiology

Human kidneys

The normal (non-transplant) kidney site in the retroperitoneal space, which is behind the lining of the abdominal cavity. When doing a kidney biopsy, it’s best to keep the needle in this space to avoid hitting other organs and causing complications.

For non-targeted biopsies, doctors usually take tissue from the renal cortex- the outer part of the kidney. That’s because the cortex contains most of the important structures needed to diagnose kidney diseases, including:

Glomeruli (where blood is filtered)

Bowman’s space

Small arteries and arterioles

Proximal and distal tubules

Early collecting ducts

The renal medulla, or inner part of the kidney, doesn’t have glomeruli. It mostly contains loops of Henle and parts of the tubules. So, sampling the medulla isn’t usually necessary, except in rare cases like:

Suspected tumors

Nephronophthisis (a rare condition with cysts at the edge of the cortex and medulla)

Medullary cystic kidney disease (though this is usually diagnosed with imaging, not biopsy)

The blood supply to the kidney generally starts from a single renal artery that splits into front (anterior) and back (posterior) branches. These arteries are “end arteries,” they don’t overlap in the areas they supply. The zone where the front and back blood supplies meet along the back side of the kidney (called Hyrtl’s or Brodel’s line) is thought to be the safest place to take a tissue sample, because it has fewer blood vessels. However, this area doesn’t show up on imaging, so the doctor must estimate where it is.

Before the biopsy, imaging tests like ultrasound, CT, or MRI are done to help plan the safest path for the needle. It’s important to remember that not everyone has “typical” kidney anatomy, some people have kidneys in unusual positions (like ectopic or horseshoe kidneys), and that may change how the procedure is done.

Unexplained Kidney Problems

Persistent hematuria (especially with proteinuria)

Nephrotic syndrome or significant proteinuria >1 g/day

Acute kidney injury (AKI) of unknown cause

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) of unclear etiology

Suspected Specific Renal Diseases

Glomerulonephritis (e.g., lupus nephritis, IgA nephropathy)

Systemic diseases with renal involvement (e.g., SLE, vasculitis, amyloidosis)

Tubulointerstitial diseases, when diagnosis is uncertain

Transplant-Related Indications

Monitoring allograft function

Unexplained rise in serum creatinine

Suspected rejection

Drug toxicity

Recurrent or de novo glomerular disease

Treatment Planning or Prognosis

To guide therapy decisions (e.g., immunosuppressive treatment)

To assess prognosis in progressive or suspected irreversible kidney disease

According to the 2016 guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA), kidney tumor biopsies are generally not recommended in certain situations:

Young, healthy individuals who prefer not to deal with the uncertainties that come with biopsy results.

Older patients who would be managed without surgery or invasive treatment, no matter what the biopsy shows.

There are also several imaging-related scenarios where a biopsy may not be helpful or could be risky:

Bleeding or protein inside a complex cyst: On ultrasound, CT, or MRI, dense fluid from bleeding or protein can look like a solid mass. Comparing scans before and after contrast, or using contrast-subtraction techniques, can help sort this out.

Pseudoenhancement: This refers to a false appearance of increased brightness or density on post-contrast scans, typically affecting small (<2 cm) soft lesions next to normal kidney tissue. These can mimic solid tumors but may not be true growths. In such cases, simply watching the lesion over time may be appropriate.

Lesions that brighten like blood vessels: If a mass lights up to the same degree as the blood vessels (like the aorta) on contrast-enhanced scans, it could be a vascular abnormality (e.g., a pseudoaneurysm) rather than a tumor. Additional testing with contrast-enhanced ultrasound or specialized MRI may be a better next step.

In these cases-such as suspected blood/protein-filled cysts or pseudoenhancement-biopsies often fail to provide useful results. For vascular lesions, biopsy carries a significant risk of bleeding and should be avoided unless necessary.

Imaging Features That Suggest a Benign Tumor

Visible fat in the mass: This is typical of a benign angiomyolipoma, especially if there are no signs of calcification or aggressive growth.

Minimal (microscopic) fat: Some angiomyolipomas don’t have visible fat but still contain small amounts inside the cells. These can look like cancer on imaging:

Kidney adenocarcinoma biopsy under light microscopy

Like papillary renal cell carcinoma, they appear dark on T2-weighted MRI.

Like clear cell carcinoma, they show strong contrast enhancement.

If both features are present, it’s more likely to be a fat-poor angiomyolipoma, not cancer.

Fast-growing, poorly defined mass in someone with a urinary tract infection: This may point to localized kidney infection (focal pyelonephritis). If the mass doesn’t go away after the infection is treated, a biopsy may be needed to check if it’s an infection or a tumor.

Imaging Equipment

Ultrasound machine

CT scanner

MRI (rarely used)

Biopsy Needles

Core biopsy needle (automated or semi-automated)

Gauge size typically ranges from 14G to 18G

Local Anesthesia

Sterile Procedure Supplies

Needle Guide/Holder

Collection Containers

Emergency Supplies

Post-Biopsy Monitoring Equipment

Patient Preparation:

The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends that patients be clearly informed about why a biopsy is being done, what the test results might mean (both good and bad), the possible risks, and the chance that the test won’t give a clear answer.

The doctor who recommends the biopsy usually a urologist or nephrologist should go over all of this with the patient before scheduling the procedure.

If the patient learns about the risks for the first time during the consent process and then decides to wait until they can talk to the referring doctor again, that decision should be respected.

Patients should also be informed about how they will be positioned during the procedure (usually lying face down or slightly to the side) and what type of pain management or medication will be used.

For hard-to-reach areas, it helps to plan the biopsy using both ultrasound and CT scans. Each has its advantages: ultrasound is quick, while CT provides clearer images of soft tissues.

Some CT-guided biopsies, particularly those targeting the upper part of the kidney, may require special techniques such as adjusting the CT scanner angle or performing calculations to determine the correct needle trajectory. To find the appropriate angle, divide the depth of the lesion by the distance from the skin surface, then use a calculator to determine the inverse tangent (arctangent) of that number, which gives the angle in degrees.

Patient position:

Prone Position

The patient lies flat on their stomach.

This is the standard position for posterior (back side) kidney access, especially for lower or mid-pole kidney lesions.

Prone Oblique Position

The patient lies on their stomach but slightly turned to one side (usually about 30 degrees).

This can improve access and comfort, especially if the target area is slightly lateral (toward the side) or if full prone is uncomfortable.

Step 1-Pre-Procedure Preparation:

Confirm indication for biopsy and review imaging to locate the kidney.

Check lab work (especially coagulation tests and platelet count).

Obtain informed consent after discussing risks and benefits with the patient.

Ensure the patient has arranged transportation home and has someone available to monitor them after the procedure.

Step 2-Position the Patient:

Prone position (lying on the stomach) is most common.

Use pillows under the abdomen for comfort and better access.

In special cases (e.g., transplant kidney), supine (on the back) may be used.

Step3-Site Localization

Use ultrasound or CT to identify the kidney and plan the biopsy path.

Typically, the lower pole of the kidney is chosen to reduce the risk of hitting large blood vessels.

Step 4-Skin Preparation and Anesthesia

Clean the skin with antiseptic.

Drape the area to maintain a sterile field.

Inject local anesthetic into the skin and deeper tissue down to the kidney capsule.

Step 5-Needle Insertion

Use image guidance to insert the biopsy needle (usually 18-gauge or smaller).

Confirm the needle is in the right position before taking samples.

Obtain 1-3 core tissue samples, depending on the quality and amount needed.

Step 6-Post-Biopsy Care

Apply pressure to the biopsy site and place a sterile bandage.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, urine color, and pain level for several hours.

Perform a follow-up ultrasound if there’s concern for bleeding or complications.

Discharge instructions include no heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 24-48 hours.

According to the 2013 practice guidelines from the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR), the risk of serious bleeding that requires a blood transfusion is expected to be less than 3% when using an 18-gauge needle or smaller. If the rate goes over 5%, it may be a sign that the procedure technique or patient selection needs to be reviewed and improved. The guidelines also mention that larger needles might slightly increase the risk of complications, but they don’t go into detail about those risks.

The following complication rates were reported:

In real-world practice, minor vascular injuries that don’t need treatment are thought to be much more common than reported in studies, especially since most studies don’t routinely use ultrasound after the biopsy to check for these injuries.

Although not mentioned in the SIR guidelines or Patel’s study, another experienced clinician found that arteriovenous fistulas (abnormal connections between arteries and veins) that needed treatment happened in about 1% of kidney biopsies. These fistulas are seen more often when doctors actively look for them using ultrasound after the procedure.

In fact, almost every patient ends up with some bleeding around the kidney (perirenal hematoma), which is easier to detect on CT or MRI than on ultrasound.

In rare but serious cases, a patient may lose a kidney due to complications. Deaths have also occurred, though they are extremely rare, following severe bleeding or other serious issues after a kidney biopsy.

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.