Background

The Pringle Maneuver is a surgical method to control liver bleeding by temporarily vascular occlusion of a hepatoduodenal ligament in the liver, which contains the portal triad: hepatic artery, portal vein and common bile duct. J.H. Pringle first described this in 1908. The maneuver is used often for liver surgery and hepatic trauma to reduce blood loss and improve surgical visualization. By clamping the portal triad, blood flow into the liver is reduced which allows the surgeon to identify sites of bleeding within the hepatic parenchyma. Clamping of the portal triad is generally regarded a safe maneuver if applied intermittently or for a short duration, but prolonged hepatic vascular occlusion may result in hepatic ischemia.

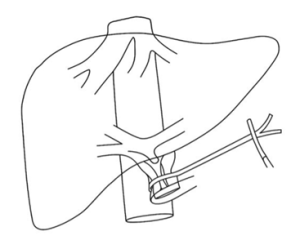

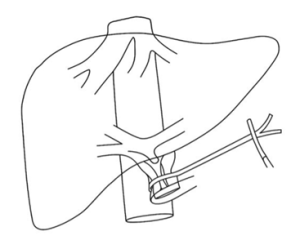

Figure 1: Pringle Maneuver

Indications

Traumatic Liver Injury (Hepatic Trauma)

To control hemorrhage from liver lacerations or parenchymal injury when bleeding is suspected to originate from the portal vein or hepatic artery.

Elective Liver Surgery (e.g., hepatectomy, tumor resection)

To reduce intraoperative blood loss during liver parenchymal transection. To improve a better surgical field in complex liver resections.

Complications of Liver Biopsy

In rare cases when bleeding cannot be kept under control following percutaneous or intraoperative liver biopsy.

Evaluation of Bleeding Source

Assists with differentiate between bleeding from hepatic inflow (which can be controlled by the Pringle Maneuver) and other sources such as the hepatic veins or the inferior vena cava which could not be controlled with the maneuver.

Control of Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients

Pringle Maneuver is used with caution during liver surgery in cirrhosis to manage bleeding, due to friable liver tissue and increased vascularity.

Contraindications

Complete Portal Vein Thrombosis

Clamping the portal triad, in this setting, could stop hepatic perfusion completely, which could lead to synchronous and fatal liver ischemia.

Hilar Malignancy Involving the Portal Triad

Clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament may lead to tumor rupture, uncontrolled bleeding, or injury to the bile duct.

Severe Cirrhosis or Poor Hepatic Reserve

The liver cannot tolerate even a short period of ischemia, and a sustained ischemic episode increases the chances of postoperative liver failure.

Prolonged Planned Occlusion Time

If the inflow occlusion is expected to exceed 60 minutes, the surgeon should consider intermittent clamping or other forms of vascular control to minimize ischemic injury.

Pre-existing Biliary Strictures or Ischemic Cholangiopathy

Further ischemia from clamping may worsen biliary damage or lead to bile leaks.

Uncontrolled Hemorrhage from Hepatic Veins or Inferior Vena Cava

The Pringle Maneuver will only control bleeding from inflow vessels. If the source of bleeding is outflow veins, it will not be effective and will delay definitive treatment.

Outcomes

Equipment

Basic Surgical Instruments

Standard Laparotomy Set or Laparoscopic Instruments

Self-retaining Retractor System (e.g., Bookwalter retractor)

Pringle Maneuver Occlusion Tools

Vascular Clamp

Soft non-crushing clamp

Rummel Tourniquet Set

Silicone Vessel Loops (especially in laparoscopic surgery)

Laparoscopic Bulldog Clamp (if performed via laparoscopy)

Hemostasis and Visualization Aids

Suction-Irrigation Device

Electrocautery or Energy Devices

Hemostatic Agents (e.g., Surgicel®, Floseal®, or TachoSil®)

Anesthesia and Monitoring

Invasive Arterial Line

Central Venous Access

Large-Bore IV Access

Blood Products and Cell Saver (if available)

Liver Retractors

Patient Preparation

Preoperative Assessment

Liver Function Tests (LFTs): To assess baseline hepatic function and reserve.

Coagulation Profile: Including INR, PT, aPTT, and platelet count to evaluate bleeding risk.

Imaging Studies: CT scan or MRI to identify hepatic lesions, vascular anatomy, and the extent of trauma or tumor.

Cardiopulmonary Evaluation: To ensure the patient can tolerate potential hemodynamic changes.

Informed Consent

Discuss the indications for hepatic inflow occlusion. Explain the complications of bleeding, liver injury and bile duct injury. Discuss the potential for conversion to open surgery or other interventions.

Optimization of Medical Status

Administer vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or platelets if needed.

Ensure adequate fluid resuscitation to maintain perfusion.

Transfuse packed red blood cells if hemoglobin is critically low.

Especially in liver resections or trauma cases.

Intraoperative Preparations

Supine position with appropriate padding. Reverse Trendelenburg may aid exposure.

Invasive blood pressure monitoring, central venous access, and possibly cardiac output monitoring.

Ensure cross-matched blood is ready for transfusion.

Prepare vascular clamps, tourniquets, or vessel loops for occlusion of the hepatoduodenal ligament.

Anesthesia Considerations

General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.

Maintenance of normovolemia and normothermia.

Preparedness for rapid fluid or vasopressor administration in case of hemodynamic instability during clamping.

Patient position

Supine Position

The patient lies flat on their back.

This provides full access to the upper abdomen for either open or laparoscopic procedures.

Reverse Trendelenburg (Head-up Tilt)

Slight elevation of the upper body (10-15°) helps shift abdominal contents downward, improving visibility of the porta hepatis.

Technique

Step 1: Anesthesia and Monitoring

The anesthesiologist administers general anesthesia and intubates the patient.

Continuous monitoring of vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, central venous pressure if needed) is established.

Step 2: Gastrointestinal and Bladder Decompression

A nasogastric tube is inserted to decompress the stomach, reducing interference in the surgical field.

A urinary catheter is placed to decompress the bladder and monitor urine output during and after the procedure.

Step 3: Patient Positioning

The patient is positioned supine, with a slight reverse Trendelenburg tilt to enhance exposure of the upper abdomen.

The arms are placed on armboards, and pressure points are padded appropriately.

Step 4: Surgical Site Preparation

The abdomen is cleaned and draped in a sterile fashion.

A midline or right subcostal incision is made to gain access to the upper abdomen.

Step 5: Exposure of the Hepatoduodenal Ligament (Portal Triad)

The surgeon opens the lesser omentum to reach the hepatoduodenal ligament.

The ligament is gently dissected to isolate the portal triad structures (hepatic artery, portal vein, and common bile duct).

Step 6: Application of the Pringle Maneuver

The portal triad is encircled using:

A Rummel tourniquet (umbilical tape or vessel loop passed through a red rubber catheter), or

A non-crushing vascular clamp (e.g., Satinsky or bulldog clamp).

The clamp or tourniquet is gently tightened to occlude hepatic inflow.

Step 7: Intermittent or Continuous Occlusion

Intermittent Technique (Preferred):

Clamp is applied for 10-20 minutes at a time.

Reperfusion allowed for 5 minutes between cycles to minimize liver ischemia.

Continuous Technique:

In selected short procedures, continuous clamping may be used (generally kept <60 minutes).

Surgical Procedure Performed

The primary liver surgery (e.g., tumor resection, hemostasis in trauma) is carried out during the occlusion phase.

Clamp Removal and Vascular Inspection

Once the critical portion of the surgery is complete, the clamp is carefully released.

The surgeon checks for:

Restoration of hepatic blood flow

Absence of bleeding or vascular injury

Step 8: Closure

Hemostasis is ensured.

Surgical drains may be placed if needed.

The abdominal incision is closed in layers using sutures or staples.

Step 9: Post-procedure Phase

Recovery from Anesthesia

The patient is gradually awakened from anesthesia and extubated once stable.

Vital signs and urine output continue to be closely monitored.

Postoperative Observation

The patient is transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) or intensive care unit (ICU) based on the surgical complexity and condition.

Pain management is initiated with intravenous or oral analgesics.

Hospital Stay and Monitoring

Most patients require hospitalization for several days to a week.

Liver function tests (LFTs), coagulation profile, and hemoglobin levels are monitored.

Imaging (e.g., Doppler ultrasound or CT) may be done postoperatively if complications are suspected.

Complications

Hepatic Ischemia and Necrosis

Prolonged clamping (>60 minutes continuously or repeated prolonged intermittent occlusion) can lead to liver cell injury or necrosis due to impaired blood supply.

Reperfusion Injury

When blood flow is restored after occlusion, oxidative stress and inflammation can result in additional tissue damage, known as ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Bile Duct Injury

Compression or ischemia of the bile duct may lead to biliary stricture or leakage, especially in repeated or prolonged occlusions.

Hemodynamic Instability

Sudden inflow occlusion can cause a drop in cardiac output or splanchnic congestion, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular instability or cirrhosis.

Portal Hypertension Exacerbation

In cirrhotic patients, clamping the portal vein can worsen portal hypertension, potentially leading to variceal rupture or ascites.

Inadequate Hemorrhage Control

If bleeding originates from the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava (outflow structures), the Pringle Maneuver will not stop the hemorrhage, potentially delaying definitive management.

The Pringle Maneuver is a surgical method to control liver bleeding by temporarily vascular occlusion of a hepatoduodenal ligament in the liver, which contains the portal triad: hepatic artery, portal vein and common bile duct. J.H. Pringle first described this in 1908. The maneuver is used often for liver surgery and hepatic trauma to reduce blood loss and improve surgical visualization. By clamping the portal triad, blood flow into the liver is reduced which allows the surgeon to identify sites of bleeding within the hepatic parenchyma. Clamping of the portal triad is generally regarded a safe maneuver if applied intermittently or for a short duration, but prolonged hepatic vascular occlusion may result in hepatic ischemia.

Figure 1: Pringle Maneuver

Traumatic Liver Injury (Hepatic Trauma)

To control hemorrhage from liver lacerations or parenchymal injury when bleeding is suspected to originate from the portal vein or hepatic artery.

Elective Liver Surgery (e.g., hepatectomy, tumor resection)

To reduce intraoperative blood loss during liver parenchymal transection. To improve a better surgical field in complex liver resections.

Complications of Liver Biopsy

In rare cases when bleeding cannot be kept under control following percutaneous or intraoperative liver biopsy.

Evaluation of Bleeding Source

Assists with differentiate between bleeding from hepatic inflow (which can be controlled by the Pringle Maneuver) and other sources such as the hepatic veins or the inferior vena cava which could not be controlled with the maneuver.

Control of Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients

Pringle Maneuver is used with caution during liver surgery in cirrhosis to manage bleeding, due to friable liver tissue and increased vascularity.

Complete Portal Vein Thrombosis

Clamping the portal triad, in this setting, could stop hepatic perfusion completely, which could lead to synchronous and fatal liver ischemia.

Hilar Malignancy Involving the Portal Triad

Clamping the hepatoduodenal ligament may lead to tumor rupture, uncontrolled bleeding, or injury to the bile duct.

Severe Cirrhosis or Poor Hepatic Reserve

The liver cannot tolerate even a short period of ischemia, and a sustained ischemic episode increases the chances of postoperative liver failure.

Prolonged Planned Occlusion Time

If the inflow occlusion is expected to exceed 60 minutes, the surgeon should consider intermittent clamping or other forms of vascular control to minimize ischemic injury.

Pre-existing Biliary Strictures or Ischemic Cholangiopathy

Further ischemia from clamping may worsen biliary damage or lead to bile leaks.

Uncontrolled Hemorrhage from Hepatic Veins or Inferior Vena Cava

The Pringle Maneuver will only control bleeding from inflow vessels. If the source of bleeding is outflow veins, it will not be effective and will delay definitive treatment.

Basic Surgical Instruments

Standard Laparotomy Set or Laparoscopic Instruments

Self-retaining Retractor System (e.g., Bookwalter retractor)

Pringle Maneuver Occlusion Tools

Vascular Clamp

Soft non-crushing clamp

Rummel Tourniquet Set

Silicone Vessel Loops (especially in laparoscopic surgery)

Laparoscopic Bulldog Clamp (if performed via laparoscopy)

Hemostasis and Visualization Aids

Suction-Irrigation Device

Electrocautery or Energy Devices

Hemostatic Agents (e.g., Surgicel®, Floseal®, or TachoSil®)

Anesthesia and Monitoring

Invasive Arterial Line

Central Venous Access

Large-Bore IV Access

Blood Products and Cell Saver (if available)

Liver Retractors

Preoperative Assessment

Liver Function Tests (LFTs): To assess baseline hepatic function and reserve.

Coagulation Profile: Including INR, PT, aPTT, and platelet count to evaluate bleeding risk.

Imaging Studies: CT scan or MRI to identify hepatic lesions, vascular anatomy, and the extent of trauma or tumor.

Cardiopulmonary Evaluation: To ensure the patient can tolerate potential hemodynamic changes.

Informed Consent

Discuss the indications for hepatic inflow occlusion. Explain the complications of bleeding, liver injury and bile duct injury. Discuss the potential for conversion to open surgery or other interventions.

Optimization of Medical Status

Administer vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or platelets if needed.

Ensure adequate fluid resuscitation to maintain perfusion.

Transfuse packed red blood cells if hemoglobin is critically low.

Especially in liver resections or trauma cases.

Intraoperative Preparations

Supine position with appropriate padding. Reverse Trendelenburg may aid exposure.

Invasive blood pressure monitoring, central venous access, and possibly cardiac output monitoring.

Ensure cross-matched blood is ready for transfusion.

Prepare vascular clamps, tourniquets, or vessel loops for occlusion of the hepatoduodenal ligament.

Anesthesia Considerations

General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation.

Maintenance of normovolemia and normothermia.

Preparedness for rapid fluid or vasopressor administration in case of hemodynamic instability during clamping.

Supine Position

The patient lies flat on their back.

This provides full access to the upper abdomen for either open or laparoscopic procedures.

Reverse Trendelenburg (Head-up Tilt)

Slight elevation of the upper body (10-15°) helps shift abdominal contents downward, improving visibility of the porta hepatis.

Step 1: Anesthesia and Monitoring

The anesthesiologist administers general anesthesia and intubates the patient.

Continuous monitoring of vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, central venous pressure if needed) is established.

Step 2: Gastrointestinal and Bladder Decompression

A nasogastric tube is inserted to decompress the stomach, reducing interference in the surgical field.

A urinary catheter is placed to decompress the bladder and monitor urine output during and after the procedure.

Step 3: Patient Positioning

The patient is positioned supine, with a slight reverse Trendelenburg tilt to enhance exposure of the upper abdomen.

The arms are placed on armboards, and pressure points are padded appropriately.

Step 4: Surgical Site Preparation

The abdomen is cleaned and draped in a sterile fashion.

A midline or right subcostal incision is made to gain access to the upper abdomen.

Step 5: Exposure of the Hepatoduodenal Ligament (Portal Triad)

The surgeon opens the lesser omentum to reach the hepatoduodenal ligament.

The ligament is gently dissected to isolate the portal triad structures (hepatic artery, portal vein, and common bile duct).

Step 6: Application of the Pringle Maneuver

The portal triad is encircled using:

A Rummel tourniquet (umbilical tape or vessel loop passed through a red rubber catheter), or

A non-crushing vascular clamp (e.g., Satinsky or bulldog clamp).

The clamp or tourniquet is gently tightened to occlude hepatic inflow.

Step 7: Intermittent or Continuous Occlusion

Intermittent Technique (Preferred):

Clamp is applied for 10-20 minutes at a time.

Reperfusion allowed for 5 minutes between cycles to minimize liver ischemia.

Continuous Technique:

In selected short procedures, continuous clamping may be used (generally kept <60 minutes).

Surgical Procedure Performed

The primary liver surgery (e.g., tumor resection, hemostasis in trauma) is carried out during the occlusion phase.

Clamp Removal and Vascular Inspection

Once the critical portion of the surgery is complete, the clamp is carefully released.

The surgeon checks for:

Restoration of hepatic blood flow

Absence of bleeding or vascular injury

Step 8: Closure

Hemostasis is ensured.

Surgical drains may be placed if needed.

The abdominal incision is closed in layers using sutures or staples.

Step 9: Post-procedure Phase

Recovery from Anesthesia

The patient is gradually awakened from anesthesia and extubated once stable.

Vital signs and urine output continue to be closely monitored.

Postoperative Observation

The patient is transferred to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) or intensive care unit (ICU) based on the surgical complexity and condition.

Pain management is initiated with intravenous or oral analgesics.

Hospital Stay and Monitoring

Most patients require hospitalization for several days to a week.

Liver function tests (LFTs), coagulation profile, and hemoglobin levels are monitored.

Imaging (e.g., Doppler ultrasound or CT) may be done postoperatively if complications are suspected.

Hepatic Ischemia and Necrosis

Prolonged clamping (>60 minutes continuously or repeated prolonged intermittent occlusion) can lead to liver cell injury or necrosis due to impaired blood supply.

Reperfusion Injury

When blood flow is restored after occlusion, oxidative stress and inflammation can result in additional tissue damage, known as ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Bile Duct Injury

Compression or ischemia of the bile duct may lead to biliary stricture or leakage, especially in repeated or prolonged occlusions.

Hemodynamic Instability

Sudden inflow occlusion can cause a drop in cardiac output or splanchnic congestion, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular instability or cirrhosis.

Portal Hypertension Exacerbation

In cirrhotic patients, clamping the portal vein can worsen portal hypertension, potentially leading to variceal rupture or ascites.

Inadequate Hemorrhage Control

If bleeding originates from the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava (outflow structures), the Pringle Maneuver will not stop the hemorrhage, potentially delaying definitive management.

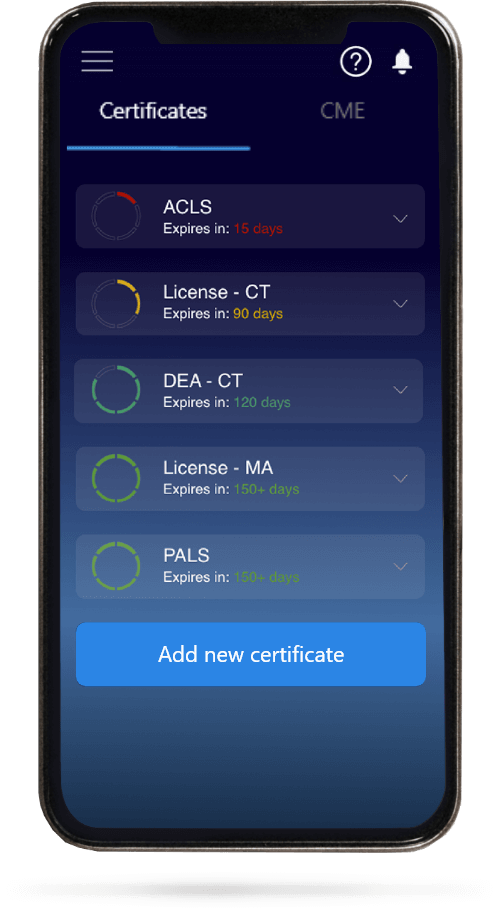

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.