Sleepless and Costly: How OSA Is Hitting US and UK Workforces

March 3, 2026

Background

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect humans’ gastrointestinal tract, particularly the large intestine (colon). It was first identified in 1918 by Jepps and Dobell. Dientamoeba fragilis is a non-flagellated, binucleate amoeba. It lacks a distinct cyst stage, which differentiates it from many other parasitic organisms.

The life cycle of Dientamoeba fragilis is not entirely clear, and it is somewhat controversial. Transmission is likely through the ingestion of cysts, but the exact details of cyst formation and the transmission process still need to be better understood.

Dientamoeba fragilis can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. The role of Dientamoeba fragilis as a pathogen is still a subject of debate among researchers. Some individuals infected with the parasite may remain asymptomatic, while others may experience symptoms.

Diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection is typically made through the examination of stool samples for the presence of the organism. Microscopic identification of trophozoites (the active feeding stage) in fresh or preserved stool specimens is the primary method of diagnosis.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of Dientamoeba fragilis is less well-defined than that of some other intestinal parasites, and there are challenges in determining the true prevalence of infections.

Global Distribution: Dientamoeba fragilis has been reported worldwide, with cases documented in various countries across different continents.

Prevalence: The prevalence of Dientamoeba fragilis varies widely in different regions. Some studies have reported relatively high prevalence rates in certain populations, while in other areas, the prevalence may be lower.

Age Distribution: Infections with Dientamoeba fragilis can occur in individuals of all age groups, including children and adults.

Transmission: The exact mode of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis is not well understood. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, with the ingestion of cysts being the proposed method of infection. However, the specific sources and mechanisms of transmission remain areas of ongoing research.

Asymptomatic Infections: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic, meaning they do not show signs of illness. Asymptomatic carriers can potentially contribute to the spread of the parasite.

Association with Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Dientamoeba fragilis has been associated with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. However, not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections exhibit symptoms, adding complexity to the understanding of its pathogenicity.

Diagnostic Challenges: The diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infections can be challenging. Microscopic identification of trophozoites in stool samples is the primary diagnostic method, but the sensitivity of detection may vary.

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections may occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections can complicate clinical presentations and diagnosis.

Anatomy

Pathophysiology

Trophozoite Stage:

The trophozoite is the active feeding stage of Dientamoeba fragilis. It is responsible for the pathogenic effects in the host.

Trophozoites are often found in the mucosal layer of the large intestine, where they can adhere to and potentially damage the intestinal epithelial cells.

Lack of Cyst Stage:

Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis does not have a distinct cyst stage in its life cycle. Cysts are a dormant, resistant form that facilitates transmission.

Adherence to Intestinal Epithelium:

Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are thought to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine.

Adherence may contribute to the pathogenesis of the infection, potentially causing irritation and damage to the intestinal epithelium.

Inflammatory Response:

Dientamoeba fragilis infections have been associated with mild to moderate inflammation of the intestinal mucosa.

The inflammatory response may contribute to the gastrointestinal symptoms observed in infected individuals.

Symptoms:

The pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue are not completely understood.

It is hypothesized that the presence of Dientamoeba fragilis and its interactions with the host’s immune system may play a role in the manifestation of symptoms.

Host Immune Response:

The host immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis is an area of ongoing research. The parasite may elicit both innate and adaptive immune responses in the host.

The clinical course of the infection may depend on how well the host’s immune system works in tandem with the parasite’s capacity to avoid or resist clearance.

Asymptomatic Infections:

Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis remain asymptomatic. The factors determining whether an infection becomes symptomatic or not are not well understood and may involve a complex interplay of host and parasite factors.

Transmission Dynamics:

The exact mode of transmission and the sources of Dientamoeba fragilis infections are not fully elucidated. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, but the details of cyst formation, shedding, and transmission mechanisms are areas of active investigation.

Etiology

Transmission:

Fecal-Oral Route: Dientamoeba fragilis is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, where ingestion of contaminated food, water, or surfaces with cysts leads to infection.

Lack of Cyst Stage: Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis lacks a distinct cyst stage, which complicates the understanding of its transmission dynamics.

Host Susceptibility:

Age and Immune Status: Individuals of all age groups can be affected by Dientamoeba fragilis. The role of age and immune status in susceptibility to infection has yet to be fully elucidated.

Asymptomatic Carriers: Some individuals may harbor Dientamoeba fragilis without showing symptoms, contributing to the complexity of understanding host susceptibility.

Environmental Factors:

Poor Sanitation: Inadequate sanitation and hygiene practices can increase the risk of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Contaminated Water and Food: Consumption of contaminated water or food, particularly in settings with poor sanitation, is a potential source of infection.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms:

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections may influence the clinical presentation and severity of symptoms.

Adherence and Colonization:

Intestinal Adherence: Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are believed to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine. This adherence may contribute to the colonization and potential pathogenic effects in the host.

Geographic Distribution:

Dientamoeba fragilis has a global distribution, and its prevalence may vary in different geographic regions. Regional differences in environmental conditions and sanitation practices may impact transmission rates.

Genetic Diversity:

Studies have suggested genetic diversity among Dientamoeba fragilis isolates, indicating the presence of different strains. The implications of this diversity on transmission, virulence, and clinical outcomes are areas of ongoing research.

Genetics

Prognostic Factors

Symptom Persistence: In many cases, Dientamoeba fragilis infections are associated with mild, self-limiting symptoms that resolve without specific treatment. The prognosis may be more favorable in cases where symptoms are transient.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals may carry Dientamoeba fragilis without exhibiting symptoms. The long-term outcome in asymptomatic carriers is not well-defined, and the significance of asymptomatic carriage is a subject of ongoing research.

Host Immune Response: The host’s immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis may influence the course of infection. Individuals with a robust immune response may be better equipped to clear the infection.

Co-Infections: The presence of Dientamoeba fragilis as a single infection or in combination with other gastrointestinal pathogens can influence the clinical presentation and prognosis. Co-infections may complicate the assessment of prognostic factors.

Treatment Response: In cases where treatment is administered, the response to antiparasitic medications may impact the prognosis. Some individuals may experience resolution of symptoms with appropriate treatment.

Clinical History

Age Group:

Children: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur in children, and symptoms may include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and general discomfort. Children may not always be able to articulate their symptoms clearly, so behavioral changes or changes in bowel habits may be observed.

Adults: Adults with Dientamoeba fragilis infections may experience similar gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue.

Physical Examination

Abdominal Examination: Healthcare providers may perform a physical examination of the abdomen to assess for tenderness, distension, or any signs of discomfort. Abdominal pain is a common symptom associated with Dientamoeba fragilis infections.

Vital Signs: Monitoring vital signs, such as temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure, can help assess the overall health of the patient and identify signs of systemic illness.

Assessment of Hydration Status: Gastrointestinal infections, including those caused by parasites like Dientamoeba fragilis, can lead to dehydration. Healthcare providers may assess the patient’s hydration status by evaluating factors such as skin turgor, mucous membrane moisture, and urine output.

Evaluation of General Well-Being: Healthcare providers will generally observe the patient’s overall appearance, looking for signs of fatigue, weakness, or distress.

Age group

Associated comorbidity

Immunocompromised Individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, may experience more severe or prolonged symptoms.

Travelers: Individuals who travel to areas with poor sanitation may be at an increased risk of Dientamoeba fragilis infection due to potential exposure to contaminated food or water.

Associated activity

Acuity of presentation

Acute Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can present acutely with sudden onset of gastrointestinal symptoms. In some cases, symptoms may be self-limiting, and the infection resolves without specific treatment.

Chronic Infections: While Dientamoeba fragilis infections are often acute and self-limiting, chronic infections have been reported. Chronic cases may involve persistent or recurrent symptoms over an extended period.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic carriers, meaning they do not show any noticeable symptoms.

Differential Diagnoses

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): It is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by bloating, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits. It can share symptoms with Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can cause chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Gastroenteritis: Acute infectious gastroenteritis caused by bacteria, viruses, or other parasites may present with symptoms similar to Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Giardiasis: Giardia lamblia is another intestinal parasite that can cause symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fatigue. It is often considered in the differential diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Celiac Disease: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten consumption. It can lead to gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Foodborne Illnesses: Various bacterial and viral infections transmitted through contaminated food or water can cause gastrointestinal symptoms and may be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Conditions such as functional dyspepsia and functional diarrhea may present with chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Enteric Infections: Other parasitic infections, such as Cryptosporidium or Entamoeba histolytica, can cause similar symptoms and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Procedures

Histologic Findings

Staging

Treatment Paradigm

Confirmation of Diagnosis: The first step in the treatment paradigm is confirming the diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection. This is usually done through laboratory tests, such as the microscopic examination of stool samples for the presence of trophozoites or molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Assessment of Symptoms: Healthcare providers will assess the severity of symptoms and the impact on the patient’s quality of life. Not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections require treatment, especially if they are asymptomatic.

Treatment Considerations: In cases where treatment is deemed necessary, antiparasitic medications are prescribed. The choice of medication may vary based on factors such as the patient’s age, overall health, and potential contraindications or allergies.

Commonly Used Medications:

Metronidazole: This antibiotic is commonly used to treat Dientamoeba fragilis infections. It is usually administered orally in divided doses over a specific duration, often ranging from 7 to 10 days.

Iodoquinol: An alternative medication, iodoquinol, may be used in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or when there is a need for an alternative treatment approach.

Follow-Up Testing:

After completing the course of treatment, healthcare providers may recommend follow-up testing to confirm the clearance of the infection. This may involve additional stool samples to ensure the absence of Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites.

Management of Recurrent Infections:

In cases of recurrent or persistent infections, healthcare providers may need to reassess the treatment approach. This may involve repeating the course of antiparasitic medications or considering alternative treatment options.

by Stage

by Modality

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Surgical Interventions

Hormone Therapy

Immunotherapy

Hyperthermia

Photodynamic Therapy

Stem Cell Transplant

Targeted Therapy

Palliative Care

use-of-a-non-pharmacological-approach-for-treating-dientamoeba-fragilis

Hygiene Practices:

Food and Water Safety:

Personal and Environmental Hygiene:

Quarantine and Isolation:

Probiotics and Gut Health:

Dietary Modifications:

Role of Metronidazole in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis

Metronidazole is commonly used as an antimicrobial agent for the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Here are key points regarding the role of metronidazole in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis:

Mechanism of Action:

Administration:

Effectiveness:

Follow-Up Testing:

Role of Iodoquinol in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis

Iodoquinol is an antiprotozoal medication that has been used in the treatment of various intestinal infections, including Dientamoeba fragilis.

However, it’s important to note that the use of iodoquinol for Dientamoeba fragilis infections may vary, and metronidazole is often considered the first-line treatment.

Iodoquinol may be considered as an alternative in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or if there are specific reasons for choosing an alternative treatment approach.

Use of tetracyclines and <a class="wpil_keyword_link" href="https://medtigo.com/drug/Paromomycin/" title="paromomycin" data-wpil-keyword-link="linked">paromomycin</a> in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis

Tetracyclines, which include medications like doxycycline, offer antibacterial activity that is broad-spectrum and may be useful against some protozoa.

An aminoglycoside antibiotic called paromomycin has been used to treat a few parasite infections.

use-of-intervention-with-a-procedure-in-treating-dientamoeba-fragilis

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect the human gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

The treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis typically involves the use of antimicrobial medications.

use-of-phases-in-managing-dientamoeba-fragilis

The management of Dientamoeba fragilis infection typically involves different phases, including diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Here’s an overview of the phases involved in managing Dientamoeba fragilis:

Diagnostic Phase:

Treatment Phase:

Antimicrobial Medications: The primary approach to treating Dientamoeba fragilis is the administration of antimicrobial medications.

Monitoring and Follow-Up Phase:

Preventive Measures:

Consultation with Specialists:

Medication

Future Trends

References

Dientamoeba fragilis: ncbi.nlm.nih

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect humans’ gastrointestinal tract, particularly the large intestine (colon). It was first identified in 1918 by Jepps and Dobell. Dientamoeba fragilis is a non-flagellated, binucleate amoeba. It lacks a distinct cyst stage, which differentiates it from many other parasitic organisms.

The life cycle of Dientamoeba fragilis is not entirely clear, and it is somewhat controversial. Transmission is likely through the ingestion of cysts, but the exact details of cyst formation and the transmission process still need to be better understood.

Dientamoeba fragilis can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. The role of Dientamoeba fragilis as a pathogen is still a subject of debate among researchers. Some individuals infected with the parasite may remain asymptomatic, while others may experience symptoms.

Diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection is typically made through the examination of stool samples for the presence of the organism. Microscopic identification of trophozoites (the active feeding stage) in fresh or preserved stool specimens is the primary method of diagnosis.

The epidemiology of Dientamoeba fragilis is less well-defined than that of some other intestinal parasites, and there are challenges in determining the true prevalence of infections.

Global Distribution: Dientamoeba fragilis has been reported worldwide, with cases documented in various countries across different continents.

Prevalence: The prevalence of Dientamoeba fragilis varies widely in different regions. Some studies have reported relatively high prevalence rates in certain populations, while in other areas, the prevalence may be lower.

Age Distribution: Infections with Dientamoeba fragilis can occur in individuals of all age groups, including children and adults.

Transmission: The exact mode of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis is not well understood. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, with the ingestion of cysts being the proposed method of infection. However, the specific sources and mechanisms of transmission remain areas of ongoing research.

Asymptomatic Infections: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic, meaning they do not show signs of illness. Asymptomatic carriers can potentially contribute to the spread of the parasite.

Association with Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Dientamoeba fragilis has been associated with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. However, not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections exhibit symptoms, adding complexity to the understanding of its pathogenicity.

Diagnostic Challenges: The diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infections can be challenging. Microscopic identification of trophozoites in stool samples is the primary diagnostic method, but the sensitivity of detection may vary.

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections may occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections can complicate clinical presentations and diagnosis.

Trophozoite Stage:

The trophozoite is the active feeding stage of Dientamoeba fragilis. It is responsible for the pathogenic effects in the host.

Trophozoites are often found in the mucosal layer of the large intestine, where they can adhere to and potentially damage the intestinal epithelial cells.

Lack of Cyst Stage:

Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis does not have a distinct cyst stage in its life cycle. Cysts are a dormant, resistant form that facilitates transmission.

Adherence to Intestinal Epithelium:

Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are thought to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine.

Adherence may contribute to the pathogenesis of the infection, potentially causing irritation and damage to the intestinal epithelium.

Inflammatory Response:

Dientamoeba fragilis infections have been associated with mild to moderate inflammation of the intestinal mucosa.

The inflammatory response may contribute to the gastrointestinal symptoms observed in infected individuals.

Symptoms:

The pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue are not completely understood.

It is hypothesized that the presence of Dientamoeba fragilis and its interactions with the host’s immune system may play a role in the manifestation of symptoms.

Host Immune Response:

The host immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis is an area of ongoing research. The parasite may elicit both innate and adaptive immune responses in the host.

The clinical course of the infection may depend on how well the host’s immune system works in tandem with the parasite’s capacity to avoid or resist clearance.

Asymptomatic Infections:

Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis remain asymptomatic. The factors determining whether an infection becomes symptomatic or not are not well understood and may involve a complex interplay of host and parasite factors.

Transmission Dynamics:

The exact mode of transmission and the sources of Dientamoeba fragilis infections are not fully elucidated. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, but the details of cyst formation, shedding, and transmission mechanisms are areas of active investigation.

Transmission:

Fecal-Oral Route: Dientamoeba fragilis is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, where ingestion of contaminated food, water, or surfaces with cysts leads to infection.

Lack of Cyst Stage: Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis lacks a distinct cyst stage, which complicates the understanding of its transmission dynamics.

Host Susceptibility:

Age and Immune Status: Individuals of all age groups can be affected by Dientamoeba fragilis. The role of age and immune status in susceptibility to infection has yet to be fully elucidated.

Asymptomatic Carriers: Some individuals may harbor Dientamoeba fragilis without showing symptoms, contributing to the complexity of understanding host susceptibility.

Environmental Factors:

Poor Sanitation: Inadequate sanitation and hygiene practices can increase the risk of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Contaminated Water and Food: Consumption of contaminated water or food, particularly in settings with poor sanitation, is a potential source of infection.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms:

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections may influence the clinical presentation and severity of symptoms.

Adherence and Colonization:

Intestinal Adherence: Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are believed to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine. This adherence may contribute to the colonization and potential pathogenic effects in the host.

Geographic Distribution:

Dientamoeba fragilis has a global distribution, and its prevalence may vary in different geographic regions. Regional differences in environmental conditions and sanitation practices may impact transmission rates.

Genetic Diversity:

Studies have suggested genetic diversity among Dientamoeba fragilis isolates, indicating the presence of different strains. The implications of this diversity on transmission, virulence, and clinical outcomes are areas of ongoing research.

Symptom Persistence: In many cases, Dientamoeba fragilis infections are associated with mild, self-limiting symptoms that resolve without specific treatment. The prognosis may be more favorable in cases where symptoms are transient.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals may carry Dientamoeba fragilis without exhibiting symptoms. The long-term outcome in asymptomatic carriers is not well-defined, and the significance of asymptomatic carriage is a subject of ongoing research.

Host Immune Response: The host’s immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis may influence the course of infection. Individuals with a robust immune response may be better equipped to clear the infection.

Co-Infections: The presence of Dientamoeba fragilis as a single infection or in combination with other gastrointestinal pathogens can influence the clinical presentation and prognosis. Co-infections may complicate the assessment of prognostic factors.

Treatment Response: In cases where treatment is administered, the response to antiparasitic medications may impact the prognosis. Some individuals may experience resolution of symptoms with appropriate treatment.

Age Group:

Children: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur in children, and symptoms may include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and general discomfort. Children may not always be able to articulate their symptoms clearly, so behavioral changes or changes in bowel habits may be observed.

Adults: Adults with Dientamoeba fragilis infections may experience similar gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue.

Abdominal Examination: Healthcare providers may perform a physical examination of the abdomen to assess for tenderness, distension, or any signs of discomfort. Abdominal pain is a common symptom associated with Dientamoeba fragilis infections.

Vital Signs: Monitoring vital signs, such as temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure, can help assess the overall health of the patient and identify signs of systemic illness.

Assessment of Hydration Status: Gastrointestinal infections, including those caused by parasites like Dientamoeba fragilis, can lead to dehydration. Healthcare providers may assess the patient’s hydration status by evaluating factors such as skin turgor, mucous membrane moisture, and urine output.

Evaluation of General Well-Being: Healthcare providers will generally observe the patient’s overall appearance, looking for signs of fatigue, weakness, or distress.

Immunocompromised Individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, may experience more severe or prolonged symptoms.

Travelers: Individuals who travel to areas with poor sanitation may be at an increased risk of Dientamoeba fragilis infection due to potential exposure to contaminated food or water.

Acute Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can present acutely with sudden onset of gastrointestinal symptoms. In some cases, symptoms may be self-limiting, and the infection resolves without specific treatment.

Chronic Infections: While Dientamoeba fragilis infections are often acute and self-limiting, chronic infections have been reported. Chronic cases may involve persistent or recurrent symptoms over an extended period.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic carriers, meaning they do not show any noticeable symptoms.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): It is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by bloating, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits. It can share symptoms with Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can cause chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Gastroenteritis: Acute infectious gastroenteritis caused by bacteria, viruses, or other parasites may present with symptoms similar to Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Giardiasis: Giardia lamblia is another intestinal parasite that can cause symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fatigue. It is often considered in the differential diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Celiac Disease: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten consumption. It can lead to gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Foodborne Illnesses: Various bacterial and viral infections transmitted through contaminated food or water can cause gastrointestinal symptoms and may be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Conditions such as functional dyspepsia and functional diarrhea may present with chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Enteric Infections: Other parasitic infections, such as Cryptosporidium or Entamoeba histolytica, can cause similar symptoms and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Confirmation of Diagnosis: The first step in the treatment paradigm is confirming the diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection. This is usually done through laboratory tests, such as the microscopic examination of stool samples for the presence of trophozoites or molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Assessment of Symptoms: Healthcare providers will assess the severity of symptoms and the impact on the patient’s quality of life. Not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections require treatment, especially if they are asymptomatic.

Treatment Considerations: In cases where treatment is deemed necessary, antiparasitic medications are prescribed. The choice of medication may vary based on factors such as the patient’s age, overall health, and potential contraindications or allergies.

Commonly Used Medications:

Metronidazole: This antibiotic is commonly used to treat Dientamoeba fragilis infections. It is usually administered orally in divided doses over a specific duration, often ranging from 7 to 10 days.

Iodoquinol: An alternative medication, iodoquinol, may be used in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or when there is a need for an alternative treatment approach.

Follow-Up Testing:

After completing the course of treatment, healthcare providers may recommend follow-up testing to confirm the clearance of the infection. This may involve additional stool samples to ensure the absence of Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites.

Management of Recurrent Infections:

In cases of recurrent or persistent infections, healthcare providers may need to reassess the treatment approach. This may involve repeating the course of antiparasitic medications or considering alternative treatment options.

Infectious Disease

Hygiene Practices:

Food and Water Safety:

Personal and Environmental Hygiene:

Quarantine and Isolation:

Probiotics and Gut Health:

Dietary Modifications:

Infectious Disease

Metronidazole is commonly used as an antimicrobial agent for the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Here are key points regarding the role of metronidazole in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis:

Mechanism of Action:

Administration:

Effectiveness:

Follow-Up Testing:

Infectious Disease

Iodoquinol is an antiprotozoal medication that has been used in the treatment of various intestinal infections, including Dientamoeba fragilis.

However, it’s important to note that the use of iodoquinol for Dientamoeba fragilis infections may vary, and metronidazole is often considered the first-line treatment.

Iodoquinol may be considered as an alternative in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or if there are specific reasons for choosing an alternative treatment approach.

Infectious Disease

Tetracyclines, which include medications like doxycycline, offer antibacterial activity that is broad-spectrum and may be useful against some protozoa.

An aminoglycoside antibiotic called paromomycin has been used to treat a few parasite infections.

Gastroenterology

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect the human gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

The treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis typically involves the use of antimicrobial medications.

Infectious Disease

The management of Dientamoeba fragilis infection typically involves different phases, including diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Here’s an overview of the phases involved in managing Dientamoeba fragilis:

Diagnostic Phase:

Treatment Phase:

Antimicrobial Medications: The primary approach to treating Dientamoeba fragilis is the administration of antimicrobial medications.

Monitoring and Follow-Up Phase:

Preventive Measures:

Consultation with Specialists:

Dientamoeba fragilis: ncbi.nlm.nih

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect humans’ gastrointestinal tract, particularly the large intestine (colon). It was first identified in 1918 by Jepps and Dobell. Dientamoeba fragilis is a non-flagellated, binucleate amoeba. It lacks a distinct cyst stage, which differentiates it from many other parasitic organisms.

The life cycle of Dientamoeba fragilis is not entirely clear, and it is somewhat controversial. Transmission is likely through the ingestion of cysts, but the exact details of cyst formation and the transmission process still need to be better understood.

Dientamoeba fragilis can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. The role of Dientamoeba fragilis as a pathogen is still a subject of debate among researchers. Some individuals infected with the parasite may remain asymptomatic, while others may experience symptoms.

Diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection is typically made through the examination of stool samples for the presence of the organism. Microscopic identification of trophozoites (the active feeding stage) in fresh or preserved stool specimens is the primary method of diagnosis.

The epidemiology of Dientamoeba fragilis is less well-defined than that of some other intestinal parasites, and there are challenges in determining the true prevalence of infections.

Global Distribution: Dientamoeba fragilis has been reported worldwide, with cases documented in various countries across different continents.

Prevalence: The prevalence of Dientamoeba fragilis varies widely in different regions. Some studies have reported relatively high prevalence rates in certain populations, while in other areas, the prevalence may be lower.

Age Distribution: Infections with Dientamoeba fragilis can occur in individuals of all age groups, including children and adults.

Transmission: The exact mode of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis is not well understood. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, with the ingestion of cysts being the proposed method of infection. However, the specific sources and mechanisms of transmission remain areas of ongoing research.

Asymptomatic Infections: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic, meaning they do not show signs of illness. Asymptomatic carriers can potentially contribute to the spread of the parasite.

Association with Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Dientamoeba fragilis has been associated with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue. However, not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections exhibit symptoms, adding complexity to the understanding of its pathogenicity.

Diagnostic Challenges: The diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infections can be challenging. Microscopic identification of trophozoites in stool samples is the primary diagnostic method, but the sensitivity of detection may vary.

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections may occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections can complicate clinical presentations and diagnosis.

Trophozoite Stage:

The trophozoite is the active feeding stage of Dientamoeba fragilis. It is responsible for the pathogenic effects in the host.

Trophozoites are often found in the mucosal layer of the large intestine, where they can adhere to and potentially damage the intestinal epithelial cells.

Lack of Cyst Stage:

Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis does not have a distinct cyst stage in its life cycle. Cysts are a dormant, resistant form that facilitates transmission.

Adherence to Intestinal Epithelium:

Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are thought to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine.

Adherence may contribute to the pathogenesis of the infection, potentially causing irritation and damage to the intestinal epithelium.

Inflammatory Response:

Dientamoeba fragilis infections have been associated with mild to moderate inflammation of the intestinal mucosa.

The inflammatory response may contribute to the gastrointestinal symptoms observed in infected individuals.

Symptoms:

The pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue are not completely understood.

It is hypothesized that the presence of Dientamoeba fragilis and its interactions with the host’s immune system may play a role in the manifestation of symptoms.

Host Immune Response:

The host immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis is an area of ongoing research. The parasite may elicit both innate and adaptive immune responses in the host.

The clinical course of the infection may depend on how well the host’s immune system works in tandem with the parasite’s capacity to avoid or resist clearance.

Asymptomatic Infections:

Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis remain asymptomatic. The factors determining whether an infection becomes symptomatic or not are not well understood and may involve a complex interplay of host and parasite factors.

Transmission Dynamics:

The exact mode of transmission and the sources of Dientamoeba fragilis infections are not fully elucidated. Fecal-oral transmission is likely, but the details of cyst formation, shedding, and transmission mechanisms are areas of active investigation.

Transmission:

Fecal-Oral Route: Dientamoeba fragilis is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, where ingestion of contaminated food, water, or surfaces with cysts leads to infection.

Lack of Cyst Stage: Unlike many other intestinal parasites, Dientamoeba fragilis lacks a distinct cyst stage, which complicates the understanding of its transmission dynamics.

Host Susceptibility:

Age and Immune Status: Individuals of all age groups can be affected by Dientamoeba fragilis. The role of age and immune status in susceptibility to infection has yet to be fully elucidated.

Asymptomatic Carriers: Some individuals may harbor Dientamoeba fragilis without showing symptoms, contributing to the complexity of understanding host susceptibility.

Environmental Factors:

Poor Sanitation: Inadequate sanitation and hygiene practices can increase the risk of transmission of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Contaminated Water and Food: Consumption of contaminated water or food, particularly in settings with poor sanitation, is a potential source of infection.

Interactions with Other Microorganisms:

Co-Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur as single infections or coexist with other gastrointestinal pathogens. Co-infections may influence the clinical presentation and severity of symptoms.

Adherence and Colonization:

Intestinal Adherence: Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites are believed to adhere to the mucosal lining of the large intestine. This adherence may contribute to the colonization and potential pathogenic effects in the host.

Geographic Distribution:

Dientamoeba fragilis has a global distribution, and its prevalence may vary in different geographic regions. Regional differences in environmental conditions and sanitation practices may impact transmission rates.

Genetic Diversity:

Studies have suggested genetic diversity among Dientamoeba fragilis isolates, indicating the presence of different strains. The implications of this diversity on transmission, virulence, and clinical outcomes are areas of ongoing research.

Symptom Persistence: In many cases, Dientamoeba fragilis infections are associated with mild, self-limiting symptoms that resolve without specific treatment. The prognosis may be more favorable in cases where symptoms are transient.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals may carry Dientamoeba fragilis without exhibiting symptoms. The long-term outcome in asymptomatic carriers is not well-defined, and the significance of asymptomatic carriage is a subject of ongoing research.

Host Immune Response: The host’s immune response to Dientamoeba fragilis may influence the course of infection. Individuals with a robust immune response may be better equipped to clear the infection.

Co-Infections: The presence of Dientamoeba fragilis as a single infection or in combination with other gastrointestinal pathogens can influence the clinical presentation and prognosis. Co-infections may complicate the assessment of prognostic factors.

Treatment Response: In cases where treatment is administered, the response to antiparasitic medications may impact the prognosis. Some individuals may experience resolution of symptoms with appropriate treatment.

Age Group:

Children: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can occur in children, and symptoms may include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and general discomfort. Children may not always be able to articulate their symptoms clearly, so behavioral changes or changes in bowel habits may be observed.

Adults: Adults with Dientamoeba fragilis infections may experience similar gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and fatigue.

Abdominal Examination: Healthcare providers may perform a physical examination of the abdomen to assess for tenderness, distension, or any signs of discomfort. Abdominal pain is a common symptom associated with Dientamoeba fragilis infections.

Vital Signs: Monitoring vital signs, such as temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure, can help assess the overall health of the patient and identify signs of systemic illness.

Assessment of Hydration Status: Gastrointestinal infections, including those caused by parasites like Dientamoeba fragilis, can lead to dehydration. Healthcare providers may assess the patient’s hydration status by evaluating factors such as skin turgor, mucous membrane moisture, and urine output.

Evaluation of General Well-Being: Healthcare providers will generally observe the patient’s overall appearance, looking for signs of fatigue, weakness, or distress.

Immunocompromised Individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, may experience more severe or prolonged symptoms.

Travelers: Individuals who travel to areas with poor sanitation may be at an increased risk of Dientamoeba fragilis infection due to potential exposure to contaminated food or water.

Acute Infections: Dientamoeba fragilis infections can present acutely with sudden onset of gastrointestinal symptoms. In some cases, symptoms may be self-limiting, and the infection resolves without specific treatment.

Chronic Infections: While Dientamoeba fragilis infections are often acute and self-limiting, chronic infections have been reported. Chronic cases may involve persistent or recurrent symptoms over an extended period.

Asymptomatic Carriage: Some individuals infected with Dientamoeba fragilis may remain asymptomatic carriers, meaning they do not show any noticeable symptoms.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): It is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by bloating, abdominal pain, and changes in bowel habits. It can share symptoms with Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis can cause chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Gastroenteritis: Acute infectious gastroenteritis caused by bacteria, viruses, or other parasites may present with symptoms similar to Dientamoeba fragilis infection.

Giardiasis: Giardia lamblia is another intestinal parasite that can cause symptoms like diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fatigue. It is often considered in the differential diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis.

Celiac Disease: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by gluten consumption. It can lead to gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Foodborne Illnesses: Various bacterial and viral infections transmitted through contaminated food or water can cause gastrointestinal symptoms and may be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Conditions such as functional dyspepsia and functional diarrhea may present with chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms.

Enteric Infections: Other parasitic infections, such as Cryptosporidium or Entamoeba histolytica, can cause similar symptoms and should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Confirmation of Diagnosis: The first step in the treatment paradigm is confirming the diagnosis of Dientamoeba fragilis infection. This is usually done through laboratory tests, such as the microscopic examination of stool samples for the presence of trophozoites or molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Assessment of Symptoms: Healthcare providers will assess the severity of symptoms and the impact on the patient’s quality of life. Not all individuals with Dientamoeba fragilis infections require treatment, especially if they are asymptomatic.

Treatment Considerations: In cases where treatment is deemed necessary, antiparasitic medications are prescribed. The choice of medication may vary based on factors such as the patient’s age, overall health, and potential contraindications or allergies.

Commonly Used Medications:

Metronidazole: This antibiotic is commonly used to treat Dientamoeba fragilis infections. It is usually administered orally in divided doses over a specific duration, often ranging from 7 to 10 days.

Iodoquinol: An alternative medication, iodoquinol, may be used in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or when there is a need for an alternative treatment approach.

Follow-Up Testing:

After completing the course of treatment, healthcare providers may recommend follow-up testing to confirm the clearance of the infection. This may involve additional stool samples to ensure the absence of Dientamoeba fragilis trophozoites.

Management of Recurrent Infections:

In cases of recurrent or persistent infections, healthcare providers may need to reassess the treatment approach. This may involve repeating the course of antiparasitic medications or considering alternative treatment options.

Infectious Disease

Hygiene Practices:

Food and Water Safety:

Personal and Environmental Hygiene:

Quarantine and Isolation:

Probiotics and Gut Health:

Dietary Modifications:

Infectious Disease

Metronidazole is commonly used as an antimicrobial agent for the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis infections. Here are key points regarding the role of metronidazole in the treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis:

Mechanism of Action:

Administration:

Effectiveness:

Follow-Up Testing:

Infectious Disease

Iodoquinol is an antiprotozoal medication that has been used in the treatment of various intestinal infections, including Dientamoeba fragilis.

However, it’s important to note that the use of iodoquinol for Dientamoeba fragilis infections may vary, and metronidazole is often considered the first-line treatment.

Iodoquinol may be considered as an alternative in cases where metronidazole is not well-tolerated or if there are specific reasons for choosing an alternative treatment approach.

Infectious Disease

Tetracyclines, which include medications like doxycycline, offer antibacterial activity that is broad-spectrum and may be useful against some protozoa.

An aminoglycoside antibiotic called paromomycin has been used to treat a few parasite infections.

Gastroenterology

Dientamoeba fragilis is a single-celled parasite that can infect the human gastrointestinal tract, leading to symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

The treatment of Dientamoeba fragilis typically involves the use of antimicrobial medications.

Infectious Disease

The management of Dientamoeba fragilis infection typically involves different phases, including diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Here’s an overview of the phases involved in managing Dientamoeba fragilis:

Diagnostic Phase:

Treatment Phase:

Antimicrobial Medications: The primary approach to treating Dientamoeba fragilis is the administration of antimicrobial medications.

Monitoring and Follow-Up Phase:

Preventive Measures:

Consultation with Specialists:

Dientamoeba fragilis: ncbi.nlm.nih

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

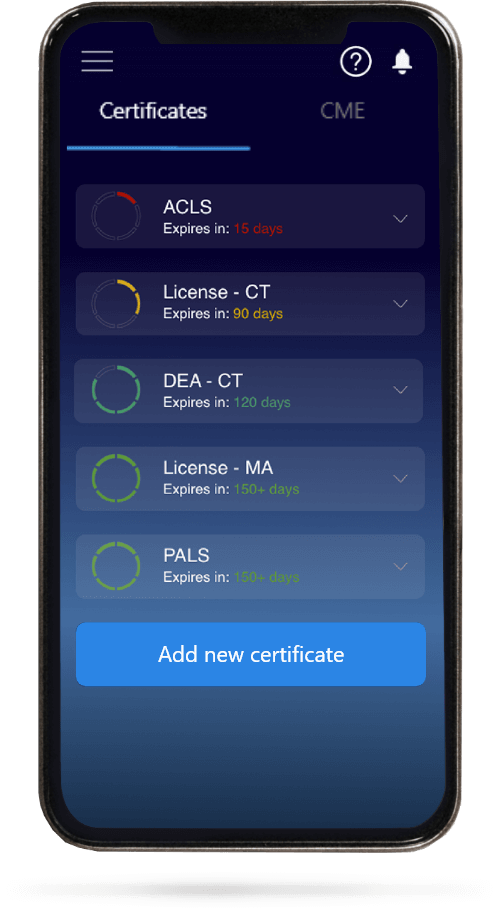

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.