Human Doctor or AI? Understanding Patient Preferences in AI-Assisted Medical Care

March 6, 2026

Background

Maduromycosis, also known as Mycetoma, is a localized and long-term infection that affects the skin and the tissues beneath it. This condition, typically caused by certain types of fungi or bacteria, commonly manifests in the limbs resulting in the development of lumps and subsequent formation of draining sinuses. The word “mycetoma” comes from the Greek words “mykes” and “toma” which refer to fungus and tumor, respectively, highlighting the distinctive nodular appearance associated with this illness. Mycetoma can also be referred to as actinomycetoma or eumycetoma depending on whether it is caused by a bacteria or fungus.

Typical causative agents include various species of fungi such as Madurella, Actinomadura, Nocardia, and Streptomyces. Mycetoma commonly presents as painless subcutaneous nodules that gradually increase in size. Over time, the nodules may become firm, and draining sinuses may form, discharging a grain-like material, which can be fungal or bacterial aggregates.

Epidemiology

Geographical Distribution:

Endemic Areas:

Causative Agents:

Risk Factors:

Gender and Age Distribution:

Anatomy

Pathophysiology

Traumatic Inoculation:

Local Tissue Invasion:

Granuloma Formation:

Chronic Inflammation:

Spread and Extension:

Immunological Response:

Granule Formation:

Etiology

Fungal Etiology (Eumycetoma): Fungal mycetomas are caused by various species of fungi, and the most common genera involved include:

Bacterial Etiology (Actinomycetoma): Actinomycetoma is caused by certain bacteria, primarily belonging to the Actinomycetes group. Common genera include:

Mixed Infections: In some cases, mycetoma can result from mixed infections involving both fungal and bacterial components. The combination of fungi and bacteria in mycetoma can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Genetics

Prognostic Factors

Early Diagnosis and Treatment:

Causative Agent:

Extent of Tissue Involvement:

Immune Status of the Host:

Patient Compliance:

Type of Treatment:

Response to Treatment:

Complications:

Availability of Healthcare Resources:

Follow-Up and Monitoring:

Clinical History

Age Group:

Physical Examination

Inspection of Skin Lesions:

Palpation of Subcutaneous Nodules:

Evaluation of Sinus Tracts:

Characterization of Grains:

Assessment of Skin Erythema and Induration:

Examination of Surrounding Tissues:

Search for Satellite Lesions:

Assessment of Systemic Symptoms:

Age group

Associated comorbidity

Associated activity

Acuity of presentation

Differential Diagnoses

Actinomycosis:

Bacterial Abscess:

Deep Fungal Infections:

Foreign Body Granuloma:

Nocardiosis:

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Procedures

Histologic Findings

Staging

Treatment Paradigm

Medical Treatment:

Surgical Treatment:

Adjunctive Therapies:

by Stage

by Modality

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Surgical Interventions

Hormone Therapy

Immunotherapy

Hyperthermia

Photodynamic Therapy

Stem Cell Transplant

Targeted Therapy

Palliative Care

use-of-a-non-pharmacological-approach-for-treating-maduromycosis-or-mycetoma

Wound Care and Hygiene:

Patient Education:

Nutritional Support:

Psychological Support:

Physical Rehabilitation:

Preventive Measures:

Environmental Modifications:

Community Engagement:

Use of Antifungal Agents in the treatment of mycetoma (maduromycosis)

The pharmaceutical agents used in the treatment of mycetoma (maduromycosis) include antifungal medications for fungal mycetoma (eumycetoma). The specific species implicated, the causal agent, and patient-specific characteristics all influence the therapeutic selection.The medications are used to target and eliminate the fungal pathogens responsible for the infection.

Use of Antibiotics in the treatment of mycetoma (maduromycosis)

Antibiotics are a crucial component in the treatment of mycetoma caused by bacteria, leading to actinomycetoma. Actinomycetoma is characterized by the formation of granules in the affected tissues, and antibiotics are employed to target the bacterial pathogens responsible for the infection.

use-of-intervention-with-a-procedure-in-treating-mycetoma-maduromycosis

Antifungal or Antibacterial Medications:

Surgical Intervention:

Combination Therapy:

Supportive Care:

Follow-up and Long-term Care:

use-of-phases-in-managing-mycetoma-maduromycosis

Diagnostic Phase:

Medical Management Phase:

Surgical Intervention Phase:

Combination Therapy Phase:

Monitoring and Follow-up Phase:

Rehabilitation and Supportive Care Phase:

Long-Term Follow-up Phase:

Medication

Future Trends

References

Maduromycosis, also known as Mycetoma, is a localized and long-term infection that affects the skin and the tissues beneath it. This condition, typically caused by certain types of fungi or bacteria, commonly manifests in the limbs resulting in the development of lumps and subsequent formation of draining sinuses. The word “mycetoma” comes from the Greek words “mykes” and “toma” which refer to fungus and tumor, respectively, highlighting the distinctive nodular appearance associated with this illness. Mycetoma can also be referred to as actinomycetoma or eumycetoma depending on whether it is caused by a bacteria or fungus.

Typical causative agents include various species of fungi such as Madurella, Actinomadura, Nocardia, and Streptomyces. Mycetoma commonly presents as painless subcutaneous nodules that gradually increase in size. Over time, the nodules may become firm, and draining sinuses may form, discharging a grain-like material, which can be fungal or bacterial aggregates.

Geographical Distribution:

Endemic Areas:

Causative Agents:

Risk Factors:

Gender and Age Distribution:

Traumatic Inoculation:

Local Tissue Invasion:

Granuloma Formation:

Chronic Inflammation:

Spread and Extension:

Immunological Response:

Granule Formation:

Fungal Etiology (Eumycetoma): Fungal mycetomas are caused by various species of fungi, and the most common genera involved include:

Bacterial Etiology (Actinomycetoma): Actinomycetoma is caused by certain bacteria, primarily belonging to the Actinomycetes group. Common genera include:

Mixed Infections: In some cases, mycetoma can result from mixed infections involving both fungal and bacterial components. The combination of fungi and bacteria in mycetoma can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Early Diagnosis and Treatment:

Causative Agent:

Extent of Tissue Involvement:

Immune Status of the Host:

Patient Compliance:

Type of Treatment:

Response to Treatment:

Complications:

Availability of Healthcare Resources:

Follow-Up and Monitoring:

Age Group:

Inspection of Skin Lesions:

Palpation of Subcutaneous Nodules:

Evaluation of Sinus Tracts:

Characterization of Grains:

Assessment of Skin Erythema and Induration:

Examination of Surrounding Tissues:

Search for Satellite Lesions:

Assessment of Systemic Symptoms:

Actinomycosis:

Bacterial Abscess:

Deep Fungal Infections:

Foreign Body Granuloma:

Nocardiosis:

Medical Treatment:

Surgical Treatment:

Adjunctive Therapies:

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Wound Care and Hygiene:

Patient Education:

Nutritional Support:

Psychological Support:

Physical Rehabilitation:

Preventive Measures:

Environmental Modifications:

Community Engagement:

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Urology

The pharmaceutical agents used in the treatment of mycetoma (maduromycosis) include antifungal medications for fungal mycetoma (eumycetoma). The specific species implicated, the causal agent, and patient-specific characteristics all influence the therapeutic selection.The medications are used to target and eliminate the fungal pathogens responsible for the infection.

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Urology

Antibiotics are a crucial component in the treatment of mycetoma caused by bacteria, leading to actinomycetoma. Actinomycetoma is characterized by the formation of granules in the affected tissues, and antibiotics are employed to target the bacterial pathogens responsible for the infection.

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Antifungal or Antibacterial Medications:

Surgical Intervention:

Combination Therapy:

Supportive Care:

Follow-up and Long-term Care:

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Diagnostic Phase:

Medical Management Phase:

Surgical Intervention Phase:

Combination Therapy Phase:

Monitoring and Follow-up Phase:

Rehabilitation and Supportive Care Phase:

Long-Term Follow-up Phase:

Maduromycosis, also known as Mycetoma, is a localized and long-term infection that affects the skin and the tissues beneath it. This condition, typically caused by certain types of fungi or bacteria, commonly manifests in the limbs resulting in the development of lumps and subsequent formation of draining sinuses. The word “mycetoma” comes from the Greek words “mykes” and “toma” which refer to fungus and tumor, respectively, highlighting the distinctive nodular appearance associated with this illness. Mycetoma can also be referred to as actinomycetoma or eumycetoma depending on whether it is caused by a bacteria or fungus.

Typical causative agents include various species of fungi such as Madurella, Actinomadura, Nocardia, and Streptomyces. Mycetoma commonly presents as painless subcutaneous nodules that gradually increase in size. Over time, the nodules may become firm, and draining sinuses may form, discharging a grain-like material, which can be fungal or bacterial aggregates.

Geographical Distribution:

Endemic Areas:

Causative Agents:

Risk Factors:

Gender and Age Distribution:

Traumatic Inoculation:

Local Tissue Invasion:

Granuloma Formation:

Chronic Inflammation:

Spread and Extension:

Immunological Response:

Granule Formation:

Fungal Etiology (Eumycetoma): Fungal mycetomas are caused by various species of fungi, and the most common genera involved include:

Bacterial Etiology (Actinomycetoma): Actinomycetoma is caused by certain bacteria, primarily belonging to the Actinomycetes group. Common genera include:

Mixed Infections: In some cases, mycetoma can result from mixed infections involving both fungal and bacterial components. The combination of fungi and bacteria in mycetoma can present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Early Diagnosis and Treatment:

Causative Agent:

Extent of Tissue Involvement:

Immune Status of the Host:

Patient Compliance:

Type of Treatment:

Response to Treatment:

Complications:

Availability of Healthcare Resources:

Follow-Up and Monitoring:

Age Group:

Inspection of Skin Lesions:

Palpation of Subcutaneous Nodules:

Evaluation of Sinus Tracts:

Characterization of Grains:

Assessment of Skin Erythema and Induration:

Examination of Surrounding Tissues:

Search for Satellite Lesions:

Assessment of Systemic Symptoms:

Actinomycosis:

Bacterial Abscess:

Deep Fungal Infections:

Foreign Body Granuloma:

Nocardiosis:

Medical Treatment:

Surgical Treatment:

Adjunctive Therapies:

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Wound Care and Hygiene:

Patient Education:

Nutritional Support:

Psychological Support:

Physical Rehabilitation:

Preventive Measures:

Environmental Modifications:

Community Engagement:

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Urology

The pharmaceutical agents used in the treatment of mycetoma (maduromycosis) include antifungal medications for fungal mycetoma (eumycetoma). The specific species implicated, the causal agent, and patient-specific characteristics all influence the therapeutic selection.The medications are used to target and eliminate the fungal pathogens responsible for the infection.

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Urology

Antibiotics are a crucial component in the treatment of mycetoma caused by bacteria, leading to actinomycetoma. Actinomycetoma is characterized by the formation of granules in the affected tissues, and antibiotics are employed to target the bacterial pathogens responsible for the infection.

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Antifungal or Antibacterial Medications:

Surgical Intervention:

Combination Therapy:

Supportive Care:

Follow-up and Long-term Care:

Dermatology, General

Infectious Disease

Internal Medicine

Pathology

Radiology

Diagnostic Phase:

Medical Management Phase:

Surgical Intervention Phase:

Combination Therapy Phase:

Monitoring and Follow-up Phase:

Rehabilitation and Supportive Care Phase:

Long-Term Follow-up Phase:

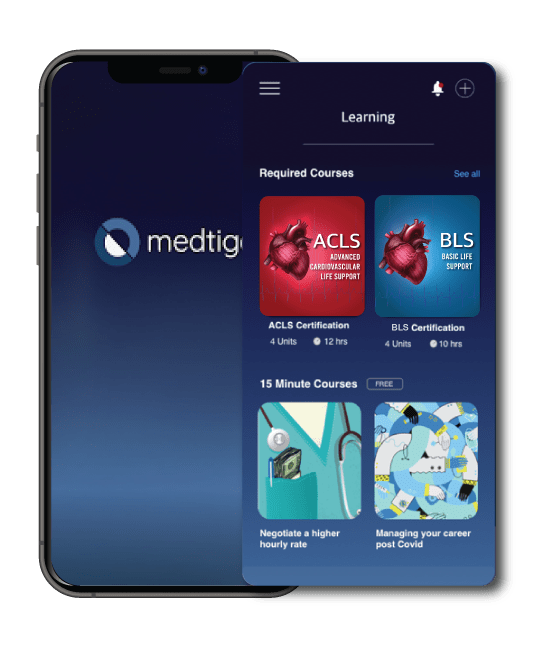

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

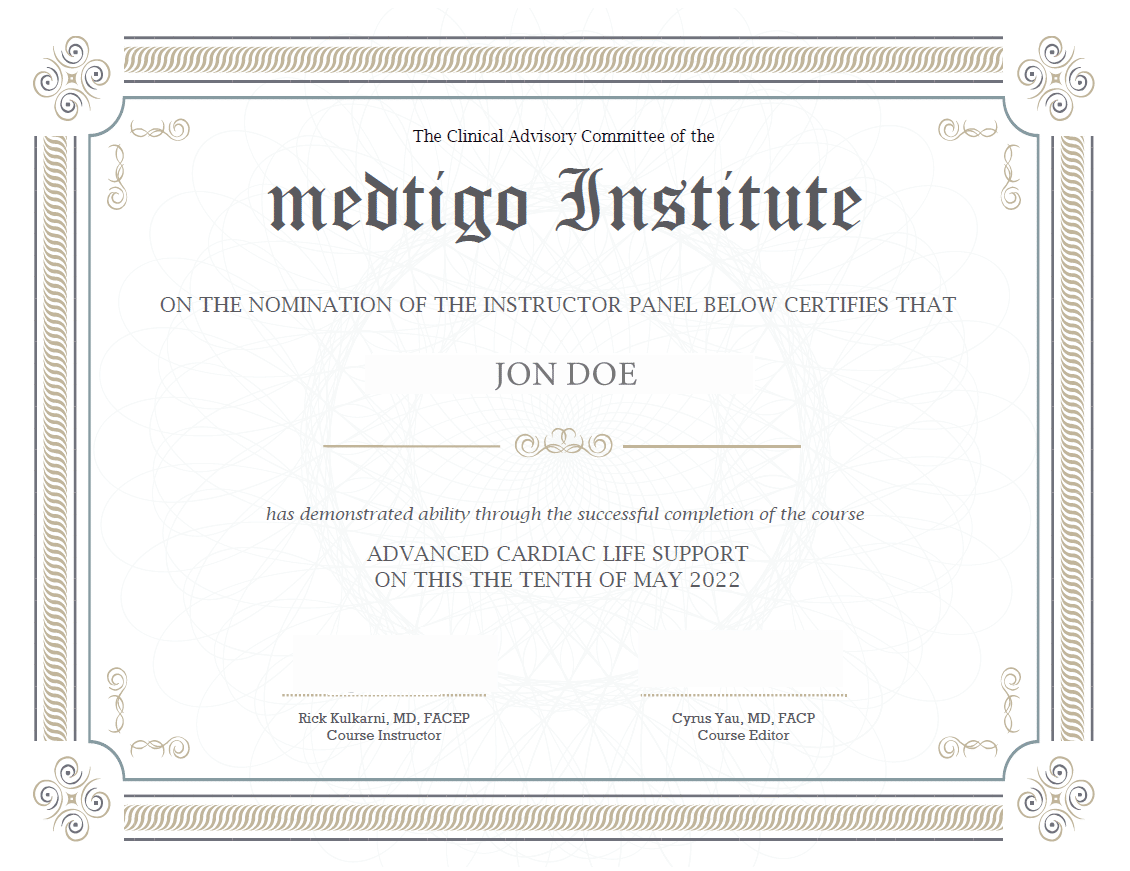

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

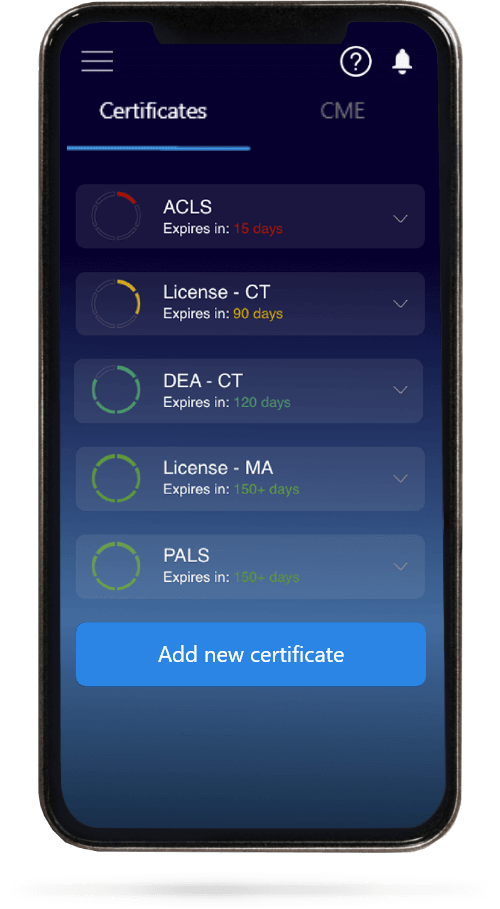

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.