CYP2D6-Guided Opioid Prescribing Fails to Improve Postoperative Pain in ADOPT PGx Randomized Trial

February 23, 2026

Background

Seizures are electrical disruptions in the nervous system that cause altered mental phenomena, dislocation, motor action, and consciousness in some frightened patients.

Abnormal and excessive electrical signals in brain neurons cause a short-term disorder in brain activity due to abnormal electrical signals.

Partial seizures are common in adults which is characterized by initial activation in a specific area of the cortex.

They often present with symptoms like motor or sensory phenomena.

Generalized seizures occur from widespread cortical activation at onset of partial seizures.

This discourse discusses the assessment and treatment of seizures emphasizing the interprofessional team role in improving patient outcomes.

It also discusses the timing for differential diagnosis and evaluation methods.

Epidemiology

Epilepsy incidence in North America ranges from 16 to 51 cases per 100,000 person-years with prevalence rate ranging from 2.2 to 41 cases per 1000.

Partial epilepsy accounts for up to two-thirds of new cases with higher incidence in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

25% to 30% of new-onset seizures are provoked and secondary to another cause.

Epilepsy incidence peaks in younger and older age brackets with cerebrovascular disease leading to cause among older individuals.

Anatomy

Pathophysiology

Excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the brain control the generation of signals and suppression of activity otherwise.

A balance between these two forces is present in a healthy brain, but it may be disturbed by depression of inhibitory system or exaggeration of excitation.

The reduction of hyperexcitability may be associated with reduced GABA function or increased glutamate sensitivity of the receptors.

However, when a group of neurons is in the hyperexcitable condition, they become persistently overexcited and, as a result, they spark multiple high-frequency action potentials.

Those axons increase the likelihood of repetitive electrical discharges by the neurons, triggering a seizure in non-related areas of the brain.

Etiology

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder, which leads to irregular electrical impulses in the brain.

It can be triggered by different life events, such as head injury, stroke, brain tumors, heredity, metabolic syndrome, or drug withdrawal.

The seizures result with the traumatic brain injuries, strokes, and brain tumors because of their irregular electrical activity.

Since hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, or kidney or liver failure, can be involved in the case then genetic factors are needed, as well.

For instance, abrupt termination of certain subsidence substances and medications is among.

Lastly, the withdrawal of medications or drugs, sudden discontinuation or change of medication or substance, can also cause seizures as well.

Genetics

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis of persons with epilepsy is determined by several factors such as the type of epilepsy, its frequency, the age when seizures develop and the genetic factors.

In children, the first onset is associated with a good prognosis, which means that their epilepsy may not be as severe as in adults.

More frequent seizures make the patient’s prognosis grimmer.

Epilepsy that begins in the early phase of life is generally considered to have a better prognosis than those which begin in adult life.

These biological factors induced, such as in turn, may elevate this risk of drug-resistant epilepsies and other propositions should occur.

Clinical History

Early childhood (0-5 years old): At this stage of developmeny from birth to 5 years, 30-40% of all seizures are febrile seizures, the episode of which is initiated when there is a rapid rise in temperature, at times accompanied by other alarming clinical signs.

Older adults (above 60 years): The incidence of epilepsy in this category also trend upward, as notable cases such as the occurrence of a stroke, a primary brain tumor, or Alzheimer’s disease tend to happen more frequent.

Physical Examination

A seizure refers to a sequence of tests to evaluate the neurological state of the person.

These tests encompass the neurological assessment, which measures the consciousness of individuals, responsiveness, muscle tone, reflexes, coordination, and sensation.

The examiner checks the head and neck for trauma; on the other hand, a cardiac exam specifically checks for abnormalities or arrhythmias.

A respiratory assessment performed, for dealing with breathing patterns and lung sounds, is used to identify any compromised state during the seizure.

Skin inspections are done to find out any skin injuries during a seizure.

The person might stay for a while in a postictal stage characterized by confusion, drowsiness, weakness, or other neurological signs.

Age group

Associated comorbidity

Associated activity

Acuity of presentation

Seizures can have different kinds of beginning, i.e., sharp, slow, abrupt, and latent.

Seizures that begin suddenly can make one lose consciousness or begin having convulsions with no warning.

Gradual seizures usually start with mild feelings until it becomes obvious.

Certain people can experience “aura” symptoms or “warning signs” such as sensory disturbances in the brain or mood changes before a seizure develops.

The postictal period includes confusion and tiredness after a seizure, and some with gradual resolution and some with quicker recovery.

Due to the urgency of seizure presentations, an immediate hyperbaric medical rescue is necessary to avoid complications and minimize the damage in the brain.

Differential Diagnoses

Epilepsy

Febrile seizures

Syncope

Metabolic disturbances

Structural brain abnormalities

Laboratory Studies

Imaging Studies

Procedures

Histologic Findings

Staging

Treatment Paradigm

Patients with reversible seizures may be discharged after appropriate interventions with adjustments to medication and follow-ups.

Noncompliant patients may need restarting antiepileptic drug regimens.

Alcohol withdrawal seizures patients can be discharged after appropriate treatment and observation with lorazepam administration reducing recurrence risk.

Adults experiencing first unprovoked seizure and returning to normal neurological function may not require immediate medical treatment but caution should be exercised until follow-up, testing, and reassessment occur.

Chronic seizure disorders can be treated with various medications including sodium channel blockers, GABA receptor agonists, GABA reuptake inhibitors, and glutamate antagonists.

For generalized convulsive status epilepticus the immediate seizure treatment should begin alongside stabilization and diagnostic procedures.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam are recommended as first-line medications but respiratory depression is a common side effect requiring careful monitoring for appropriate dosing.

Consultation with a neurologist is essential for effective treatment.

The Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) has concluded but the optimal second-line medication for benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus remains uncertain.

Second-line medications include valproate, fosphenytoin, and levetiracetam.

Advanced airway management and blood pressure support may be necessary in cases, where generalized convulsive status epilepticus persists.

The optimal treatment for refractory status epilepticus remains unknown but propofol or continuous benzodiazepine infusion in combination with other anesthetic medications.

ICU admission is typically necessary and accompanied by continuous EEG monitoring.

by Stage

by Modality

Chemotherapy

Radiation Therapy

Surgical Interventions

Hormone Therapy

Immunotherapy

Hyperthermia

Photodynamic Therapy

Stem Cell Transplant

Targeted Therapy

Palliative Care

lifestyle-modifications-in-treating-seizures

One of the most crucial triggering consequences of seizures is bright lights, tension, sleeplessness, and some drugs.

Managing mealtimes, sleep patterns, and medication schedules is very important.

Removing all potentially dangerous objects from the area and obstructions is essential.

Ensure the possibility of developing a new approach to combine the aftereffects and stave off any pain that can result from injuries.

Medical alert wristbands containing already-installed data and a GPS locator can also be installed for extra safety.

An example of this would be if someone is timely crushed by the person delivering the seizure, especially if this is occurring in dangerous environments such as stairs or swimming pools.

Role of benzodiazepines

Carbamazepine:It is used in the therapy of neuropathic pain, in addition to stabilizing the neuronal membranes,as a result of the inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels.

Oxcarbazepine: It works like carbamazepine in treating foval and generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Use of GABA inhibitor

Phenytoin: It works primarily by stabilizing the inactive state of voltage-gated sodium channels in the brain reducing the incidence of seizures.

Use of barbiturates

Phenobarbital: It enhances the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid, in the brain by binding to GABA-A receptors, which are ligand-gated chloride channels, thereby increasing the duration of chloride channel opening.

Use of carboxylic acid

Valproate: Sodium valproate is an anticonvulsant medication used in the treatment of various types of seizures, both focal and generalized.

It increases the concentration of GABA in the brain, by inhibiting degradation.

Use of GABA derivative

Vigabatrin: For focal seizures, which originate in a specific area of the brain, vigabatrin can be effective either as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy.

Role of SV2A ligands in treating myoclonic seizures

Levetiracetam: This drug functions by modulating the release of neurotransmitters, specifically by attaching itself to the synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain.

The dose to treat myoclonic seizures is 500 mg intravenously or orally two times a day and it may be enhanced every two weeks from 500 mg to 1500 mg two times a day.

Use of dicarboximide in treating absence seizures

Ethosuximide: It is considered as a first-line treatment for for absence seizures which are also known as petit mal seizures.

Use of phenyltriazines in treating absence seizures

lamotrigine: This can be used as an adjunctive therapy in treating absence seizures.

role-of-surgery-in-treating-seizures

Resective surgery:This involves removing the specific area of the brain where seizures originate.

This takes place by removing a portion of the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, or other areas depending on the location of the occurrence of seizure.

Responsive neurostimulation:This considers implanting a device called a neurostimulator, which continuously monitors brain activity and delivers electrical stimulation to interrupt or prevent seizures.

Corpus callosotomy:In some cases of severe epilepsy, that originates at same time directly from both hemispheres of the brain, the band of nerve fibres that connect the two hemispheres, the corpus callosum may be fragmented in surgical procedures to prevent seizure from spreading between the hemispheres.

use-of-phases-of-management-in-treating-seizures

The stage of assessment and diagnosis is mainly concerned with reviewing medical records in detail, physical examination as well as other diagnostic procedures like electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography to determine the nature and origin of seizure.

Persons with epilepsy or even other types of chronic seizure disorders are commonly given these kinds of antiepileptic medications.

More consistency within the lifestyle, for instance, good regular sleep, better control of the stressful environment, and the avoidance of triggering factors are good aids in reducing seizure frequency.

Regular follow up and monitoring is necessary so that the treatment plan can be maintained on the correct track.

Medication

7.5

mg

Tablet

Orally

every 8 hrs

increase by <5mg/kg

Maximum 90 mg/kg

1.5

mg

Tablet

Orally

every 8 hrs

1

week

2 - 10

mg

Orally

every 6 hrs

100

mg

Orally

every 8 hrs

a day 1 week; titrate and increase for 50 mg orally

Maintenance dose: 200 mg-400 mg orally 8 hours a day

Do not exceed 400 mg a day

Indicated for Tonic Clonic & Complex Partial Seizures :

1

g/day

Orally

in 4-6 divided doses; may be increased up to 2-3 g/day

50 mg orally/IV 2 times a day; dose can be adjusted b/w 25-100 mg orally/IV

When oral delivery is temporarily unfeasible, patients may use injections;

however, clinical study experience with injection is only available for 4 consecutive days of treatment

Note:

Used to treat partial-onset seizures

Maintenance dose: 800 to 1200mg /day

Maximum dose:1600mg/day

Immediate release:

Initial dose:

Tablets: 200mg orally twice a day

Oral suspension: 100mg orally every 6 hours

Increase every week by 200mg/dose divided every 6-8 hours

Maximum dose: 1600mg /day

Extended-release:

Initial dose: 200mg orally twice a day

Increase every week by 200mg/dose divided every 6-8 hours

Maximum dose: 1600mg /day

Initially:

100 - 125

mg

Orally

at bedtime

3

days

then 100-125 mg twice a day for 3 days

following 100-125 mg thrice a day for 3 days, then 250 mg thrice to four times a day; without exceeding 2 g/day

Dose Adjustments

Dosing considerations:

Should not exceed more than 2 g/day

Do not stop abruptly, due to the chances of risk to status epilepticus

Therapeutic efficacy may take several weeks to achieve

Initial dosages of 1-3 mg/kg/day either intravenously or orally in 1 to 2 divided doses; modify as necessary to achieve a therapeutic steady-state level of 20 mg/L

Indicated for Status Epilepticus:

Administer a loading dose of 15-20 mg/kg intravenous at a rate of 25-100 mg/min; if required, repeat in 10 minutes with an additional 5-10 mg/kg; provide respiratory support once the maximal dosage is given

Indicated for Complex Partial Seizures

10-15 mg/kg IV divided 2 times a day infused over 1 hour

May be increased to 60 mg/kg daily

Maximum duration is 14 days (AS soon as possible switch to Oral)

Complex partial seizures:

10-15 mg/kg orally daily; may increase to 5-10 mg/kg once in a week

Do not exceed 60 mg/kg a day

Conversion to Monotherapy:

Reduce the dosage of a concomitant medication by about 25% every 14 days; this dosage reduction may occur when valproate therapy is started or one to two weeks after the start of valproate therapy

simple and complex absence seizures:

Initial dose: 15 mg/kg orally divided 2-4 times a day; may increase to 5-10 mg/kg

Do not exceed 60 mg/kg a day

Indicated for Seizures

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome/Dravet syndrome:

Initial dose: 2.5 mg/kg orally two times a day

Maintenance dose: After one week, may enhance to 5 mg/kg two times a day

If a 5 mg/kg two times a day dose is tolerated, and then seizure diminishment is required. when the maintenance dose is enhanced to 10 mg/kg two times a day (20 mg/kg every day), the patient may benefit, and it may achieve by an enhanced weekly increment of 2.5 mg/kg two times a day as tolerated

If further quick titration from 10 mg/kg every day to 20 mg/kg every day is warranted, the dose might be enhanced no further frequently than the every other day

20 mg/kg every day dosage administration resulted in a somewhat substantial diminishment in rates of seizures than the 10 mg/kg every day maintenance dose, Yet with enhancement in adverse reactions

Tuberous sclerosis complex:

Initial dose: 2.5 mg/kg orally two times a day

Enhanced weekly increment of 2.5 mg/kg two times a day as tolerated to the maintenance dose of 12.5 mg/kg two times a day

If further quick titration is warranted, the dose might be enhanced no further frequently than the every other day

Dose <12.5 mg/kg two times a day, effectiveness is not studied in individuals with Tuberous sclerosis complex

Indicated for Seizures

stiripentol is indicated for treating seizures related with Dravet syndrome in patients taking clobazam. However, there is no clinical data available to support the use of stiripentol as monotherapy in Dravet syndrome

The recommended dosage for stiripentol is 50 mg/kg daily, to be administered orally in two or three divided doses (16.67 mg/kg three times a day or 25 mg/kg two times a day). The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 3000 mg

If the require dosage is not feasible with the available strengths, it is permissible to the nearest possible dosage (within 50-150 mg of 50 mg/kg daily dosage). Additionally, a mixture of the two available strengths can be used to attain the prescribed dosage

Indicated to treat stereotypic episodes (intermittent) in patients with seizure activity, which are different from usual episodes of epilepsy

The recommended starting dosage is 5 mg, administered as a single spray into one nostril

Second dose (if necessary)

If the patient does not show any response to the initial dose, an extra 5 mg (1 spray) can be administered in the opposite nostril after a 10-minute interval

However, it is important to refrain from administering a second dose if the patient has trouble breathing or if excessive sedation is unusual throughout a seizure cluster episode

Maximum dose and frequency

don't use more than two doses in each single episode of seizure

dont treat more than an episode after every 3 days and not more than five episodes each month

ER: (Only for Partial-Onset Seizures)

1000 mg once daily orally

On the basis of effectiveness and tolerability, increase in 1000 mg

increments every two weeks

1000–3000 mg taken orally once day as a maintenance dosage

3000 mg/day is the maximum dosage

IR:

500 mg IV/oral 2 times a day

Depending on effectiveness and tolerance, increase dosage twice daily in increments of 500 mg every two weeks

500 to 1500 mg intravenously or orally twice day for maintenance

3000 mg/day is the maximum dosage

Initial dose-Administer 900 mg orally, three to four times a day, in divided doses.

This dose can be increased by 300 mg weekly until therapeutic effects are noticed or toxic symptoms occur.

Maintenance dose- Administer 900 to 2400mg orally, three to four times daily, in divided doses.

Indicated for Seizure associated with status epilepticus poisoning or tetanus

The suggested dose is 5 to 10 ml intramuscularly

pipenzolate methylbromide/phenobarbitone

Put some drops in mouth daily as per physicians advised

FDA Accepted diazepam buccal (Libervant) Film NDA for treatment of seizure clusters in patients between two and five years of age

Now waiting for approval of Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA)

Dose of 75 to 125 mg should be administered as soon as possible after the convulsion starts

Status Epilepticus:

The usual dose is 4 mg per administration, delivered intravenously (IV) at a rate of 2 mg per minute, If the seizure persists for 5-10 minutes, an additional IV dose of 4 mg should be administered

1200 mg orally each day divided at an interval of 6 hours

Increase the dose to 25 mg/day every 5-7 days if required

Dosing Considerations

Obtain Echocardiogram for every 6 months while treatment, and 3-6 months soon after the final dose:

Without concomitant stiripentol

Initial dose: 0.1 mg/kg orally twice a day; should not exceed more than 26 mg/day

On Day 7: May increase up to 0.2 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 26 mg/day)

On Day 14: May increase up to 0.35 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 26 mg/day)

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam

Initial dose: 0.1 mg/kg orally twice a day; should not exceed more than 17 mg/day On Day 7: May increase dose up to 0.15 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 17 mg/day)

On Day 14: May increase dose up to 0.2 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 17 mg/day)

Dosage Modifications

Coadministration with CYP2D6 or CYP1A2 inhibitors and renal impairment

Without concomitant stiripentol: should not exceed more than 20 mg/day

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam: should Not exceed more than 17 mg/day

Hepatic impairment

Without concomitant stiripentol

(Child-Pugh A or B) Mild-to-moderate: should not exceed more than 20 mg/day

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam

(Child-Pugh A) Mild: should not exceed more than 13 mg/day

(Child-Pugh B or C) Moderate-to-severe: Usually not recommended

With enzyme-inducing but without valproic acid

Initial dose of 50 mg orally every day up to 2 weeks after that, take 100 mg/day divided in every 12 hours for 2 weeks

On 5 week and thereafter, it raised by 100 mg/day orally every 1 to 2 Week to 300 to 500 mg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

Lamotrigine XR: begin with 50 mg orally daily, after raised by 100 mg/day orally every week up to week 7 and maintenance dose of 400 to 600 mg orally daily

With valproic acid

Initial dose of 25 mg orally daily up to 2 weeks, after that, on 5 weeks it raised by 25 to 50 mg/day for every 1 to 2 weeks up to 100 to 400 mg/day daily

With valproate alone: take 100 to 200 mg/day orally

Lamotrigine XR: begin with 25, 50 mg, 100 mg and 150 mg orally daily for 2 weeks to maintenance of 200 to 250 mg

Without enzyme-inducing or valproic acid

Initial dose of 25 mg orally daily up to 2 weeks, now again take 50 mg/day orally for other 2 weeks

After 4 weeks may raised by 50 mg/day every 1 to 2 weeks up to 225 to 375 mg/day divided in every 12 hours

Lamotrigine XR: begin with 25 mg orally daily for 2 weeks, then take 50 mg orally for another 2 weeks

Then 100 mg ,150 mg and 200 mg orally daily to maintenance dose of 300 to 400 mg

With enzyme-inducing AED and no valproic acid (age 2 to 12 year)

Initial dose of 0.6 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours for 2 weeks

Take 1.2 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours for 2 weeks

At 5 weeks increase by 1.2 mg/kg every 1 to 2 week to maintenance dose of 5 to 15 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

Maximum dose of 400 mg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

With valproic acid (age <2 years)

Safety and efficacy not determined

With valproic acid (age 2 to 12 year)

Initial dose of 0.15 mg/kg/day orally then take 0.3 mg/kg/day orally for 2 weeks

On 5 weeks raised by 0.3 mg/kg every 1 to 2 weeks to maintenance dose of 1 to 5 mg/kg/day orally and maximum dose of 200 mg/day

subsequently, 1 to 3 mg/kg/day orally with valproic acid only

With valproic acid (age >12 year)

Initial dose of 25 mg orally for 2 weeks and Take 25 mg orally for another 2 weeks

On 5 weeks may raise by 25 to 50 mg/day every 1 to 2 week to 100 to 400 mg/day orally

100 to 200 mg/day orally with valproate alone

Lamotrigine XR: begin 25 mg orally daily for 2 weeks then 50 mg, 100 mg and 150 mg daily; after that 200 to 250 mg orally

Without valproic acid or AED (age <2 year)

Safety and efficacy not determined

Without valproic acid or AED (age 2-12 year)

Initial dose of 0.3 mg/kg/day orally for 2 weeks;

Take 0.6 mg/kg/day orally for another 2 weeks, then

On 5 weeks raise by 0.6 mg/kg every 1 to 2 weeks to maintenance dose of 4.5 to 7.5 mg/kg/day orally and maximum up to 300 mg/day

Without valproic acid or AED (age >12 year)

Initial dose of 25 mg orally for 2 weeks, after that

Take 50 mg/day orally for another 2 weeks;

On 5 weeks may raise by 50 mg/day every 1 to 2 week to 225 to 375 mg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

Lamotrigine XR: begin with 25 mg orally, 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg every day for 2 weeks and their after 300 to 400 mg orally

With enzyme-inducing AED and no valproic acid (age 2 to 12 year)

Initial dose of 0.6 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours for 2 weeks

Take 1.2 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours for 2 weeks

At 5 weeks increase by 1.2 mg/kg every 1 to 2 week to maintenance dose of 5 to 15 mg/kg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

Maximum dose of 400 mg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

With valproic acid (age <2 years)

Safety and efficacy not determined

With valproic acid (age 2 to 12 year)

Initial dose of 0.15 mg/kg/day orally then take 0.3 mg/kg/day orally for 2 weeks

On 5 weeks raised by 0.3 mg/kg every 1 to 2 weeks to maintenance dose of 1 to 5 mg/kg/day orally and maximum dose of 200 mg/day

subsequently, 1 to 3 mg/kg/day orally with valproic acid only

With valproic acid (age >12 year)

Initial dose of 25 mg orally for 2 weeks and Take 25 mg orally for another 2 weeks

On 5 weeks may raise by 25 to 50 mg/day every 1 to 2 week to 100 to 400 mg/day orally

100 to 200 mg/day orally with valproate alone

Lamotrigine XR: begin 25 mg orally daily for 2 weeks then 50 mg, 100 mg and 150 mg daily; after that 200 to 250 mg orally

Without valproic acid or AED (age <2 year)

Safety and efficacy not determined

Without valproic acid or AED (age 2-12 year)

Initial dose of 0.3 mg/kg/day orally for 2 weeks;

Take 0.6 mg/kg/day orally for another 2 weeks, then

On 5 weeks raise by 0.6 mg/kg every 1 to 2 weeks to maintenance dose of 4.5 to 7.5 mg/kg/day orally and maximum up to 300 mg/day

Without valproic acid or AED (age >12 year)

Initial dose of 25 mg orally for 2 weeks, after that

Take 50 mg/day orally for another 2 weeks;

On 5 weeks may raise by 50 mg/day every 1 to 2 week to 225 to 375 mg/day orally divided in every 12 hours

Lamotrigine XR: begin with 25 mg orally, 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg every day for 2 weeks and their after 300 to 400 mg orally

1.5

mg

Tablet

Orally

every 8 hrs

1

week

Indicated for Tonic Clonic & Complex Partial Seizures :

750

mg/day

Orally

in 4-6 divided doses; increased up to 500 mg-1 g/day

Age: 1 month-16 years

Wt <11 kg: 0.75-1.5 mg/kg orally every 12 hours; may be increased to 0.75-3 mg/kg

Wt 11-<20 kg: 0.5-1.25 mg/kg orally every 12 hours; may be increased to 0.5 to 2.5 mg/kg

Wt 20-<50 kg: 0.5 to 1 mg/kg orally every 12 hours; may be increased to 0.5 to 2 mg/kg

Wt ≥50 kg: 25-50 mg orally every 12 hours; may be increased to 25 to 100 mg

Age: ≥16 years

50 mg orally every 12 hours; may be increased to 25 mg-100 mg

Note:

Used to treat partial-onset seizures

Indicated for epilepsy:

<6 years of age:

Initial dose(Oral suspension):10 to 20mg/kg/day orally every 6 hours

Initial dose(Tablet): 10 to 20mg/kg/day orally every 8-12 hours

Maintenance dose:400 to 800mg/day

Maximum dose: 1000mg/day

6-12 years:

Initial dose(Oral suspension):100mg orally every 6 hours

Initial dose(Tablet): 100mg orally every 12 hours

Maintenance dose:400 to 800mg/day

Maximum dose: 1000mg/day

Over 12 years of age:

Initial dose(Oral suspension):100mg orally every 6 hours

Initial dose(Tablet): 200mg orally every 12 hours

Maintenance dose:800 to 1200mg/day

Maximum dose: 1000mg/day

Neonates (<28 days): 3 to 5 mg/kg/day in 1 to 2 divided doses intravenous or orally

Infants: 5 to 6 mg/kg/day in 1 to 2 divided doses intravenous or orally

1-5 years: 6-8 mg/kg/day in 1 to 2 divided doses intravenous or orally

6-12 years: 4-6 mg/kg/day in 1 to 2 divided doses intravenous or orally

>12 years: 1-3 mg/kg/day in 1-2 divided doses intravenous or orally, OR 50-100 mg twice or thrice a day

Infants and young children: 15-20 mg/kg intravenous given at a maximum rate of 2 mg/kg/min; Do not exceed 1000 mg/dose

<60 kg: <30 mg/min intravenous rate

When required, repeat with a 5-10 mg/kg bolus dosage after 15-30 minutes; do not exceed a total dose of 40 mg/kg

Indicated for Complex Partial Seizures

10-15 mg/kg IV divided 2 times a day infused over 1 hour

May be increased to 60 mg/kg daily

Maximum duration is 14 days (AS soon as possible switch to Oral)

Complex partial seizures:

10-15 mg/kg orally daily; may increase to 5-10 mg/kg once in a week

Do not exceed 60 mg/kg a day

Conversion to Monotherapy:

Reduce the dosage of a concomitant medication by about 25% every 14 days; this dosage reduction may occur when valproate therapy is started or one to two weeks after the start of valproate therapy

simple and complex absence seizures:

Initial dose: 15 mg/kg orally divided 2-4 times a day; may increase to 5-10 mg/kg

Do not exceed 60 mg/kg a day

Indicated for Seizures

Age >1 years

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome/Dravet syndrome:

Initial dose: 2.5 mg/kg orally two times a day

Maintenance dose: After one week, may enhance to 5 mg/kg two times a day

If a 5 mg/kg two times a day dose is tolerated, and then seizure diminishment is required. when the maintenance dose is enhanced to 10 mg/kg two times a day (20 mg/kg every day), the patient may benefit, and it may achieve by an enhanced weekly increment of 2.5 mg/kg two times a day as tolerated

If further quick titration from 10 mg/kg every day to 20 mg/kg every day is warranted, the dose might be enhanced no further frequently than the every other day

20 mg/kg every day dosage administration resulted in a somewhat substantial diminishment in rates of seizures than the 10 mg/kg every day maintenance dose, Yet with enhancement in adverse reactions

Tuberous sclerosis complex:

Initial dose: 2.5 mg/kg orally two times a day

Enhanced weekly increment of 2.5 mg/kg two times a day as tolerated to the maintenance dose of 12.5 mg/kg two times a day

If further quick titration is warranted, the dose might be enhanced no further frequently than the every other day

Dose <12.5 mg/kg two times a day, effectiveness is not studied in individuals with Tuberous sclerosis complex

Indicated for seizures

For patients who are between 6 months to less than 1 year old and weigh at least 7 kg, the recommended dosage for stiripentol is 25 mg/kg two times a day orally. The BID dosing frequency should not be exceeded to limit free water administration and prevent overexposure to the medication.

For patients who weigh between 7 kg to less than 10 kg, the recommended dosage for stiripentol is also 25 mg/kg two times a day orally. The BID dosing frequency should not be exceeded to avoid overexposure to the medication

When rounding to the nearest possible dosage, it is usually recommended to stay within 50-150 mg of the recommended 50 mg/kg/day dosage. In case the exact dosage cannot be achieved with the available strengths, a combination of the two available strengths can be used to achieve the prescribed dosage. The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 3000 mg

For patients who are 1 year old or older and weigh at least 10 kg, the recommended dosage for stiripentol is 25 mg/kg two times a day orally or 16.67 mg/kg three times a day orally. The maximum daily dosage should not exceed 3000 mg

For age ≥12 years

Indicated to treat stereotypic episodes (intermittent) in patients with seizure activity, which are different from usual episodes of epilepsy for children ≥12 years of age.

The recommended starting dosage is 5 mg, administered as a single spray into one nostril

Second dose (if necessary)

If the patient does not show any response to the initial dose, an extra 5 mg (1 spray) can be administered in the opposite nostril after a 10-minute interval

However, it is important to refrain from administering a second dose if the patient has trouble breathing or if excessive sedation is unusual throughout a seizure cluster episode

Maximum dose and frequency

don't use more than 2 doses in each single episode of seizure

dont treat more than an episode after every 3 days and not more than 5 episodes each month

In divided doses, administer 300 to 900 mg orally three to four times daily.

Indicated for Seizure associated with status epilepticus

The suggested dose is 0.1-0.15 ml/kg, each dose every 3-6 times a day by intramuscular route

For 1 year or older administer dose of 2 to 3 mg/kg intravenously

1200 mg orally each day divided at an interval of 6 hours

Increase the dose to 25 mg/day every 5-7 days if required

Dosing Considerations

Obtain Echocardiogram for every 6 months while treatment, and 3-6 months soon after the final dose :

Without concomitant stiripentol

Initial dose: 0.1 mg/kg orally twice a day; should not exceed more than 26 mg/day

On Day 7: May increase up to 0.2 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 26 mg/day)

On Day 14: May increase up to 0.35 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 26 mg/day)

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam

Initial dose: 0.1 mg/kg orally twice a day; should not exceed more than 17 mg/day

On Day 7: May increase dose up to 0.15 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 17 mg/day)

On Day 14: May increase dose up to 0.2 mg/kg orally twice a day (maximum of 17 mg/day)

Dosage Modifications

Coadministration with CYP2D6 or CYP1A2 inhibitors and Renal impairment

Without concomitant stiripentol: should not exceed more than 20 mg/day

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam: should Not exceed more than 17 mg/day

Hepatic impairment

Without concomitant stiripentol

(Child-Pugh A or B) Mild-to-moderate: should not exceed more than 20 mg/day

(Child-Pugh C) Severe: should not exceed more than 17 mg/day

With concomitant stiripentol and clobazam

(Child-Pugh A) Mild: should not exceed more than 13 mg/day

(Child-Pugh B or C) Moderate-to-severe: Usually not recommended

Future Trends

References

Seizure Medications – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

Seizures are electrical disruptions in the nervous system that cause altered mental phenomena, dislocation, motor action, and consciousness in some frightened patients.

Abnormal and excessive electrical signals in brain neurons cause a short-term disorder in brain activity due to abnormal electrical signals.

Partial seizures are common in adults which is characterized by initial activation in a specific area of the cortex.

They often present with symptoms like motor or sensory phenomena.

Generalized seizures occur from widespread cortical activation at onset of partial seizures.

This discourse discusses the assessment and treatment of seizures emphasizing the interprofessional team role in improving patient outcomes.

It also discusses the timing for differential diagnosis and evaluation methods.

Epilepsy incidence in North America ranges from 16 to 51 cases per 100,000 person-years with prevalence rate ranging from 2.2 to 41 cases per 1000.

Partial epilepsy accounts for up to two-thirds of new cases with higher incidence in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

25% to 30% of new-onset seizures are provoked and secondary to another cause.

Epilepsy incidence peaks in younger and older age brackets with cerebrovascular disease leading to cause among older individuals.

Excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the brain control the generation of signals and suppression of activity otherwise.

A balance between these two forces is present in a healthy brain, but it may be disturbed by depression of inhibitory system or exaggeration of excitation.

The reduction of hyperexcitability may be associated with reduced GABA function or increased glutamate sensitivity of the receptors.

However, when a group of neurons is in the hyperexcitable condition, they become persistently overexcited and, as a result, they spark multiple high-frequency action potentials.

Those axons increase the likelihood of repetitive electrical discharges by the neurons, triggering a seizure in non-related areas of the brain.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder, which leads to irregular electrical impulses in the brain.

It can be triggered by different life events, such as head injury, stroke, brain tumors, heredity, metabolic syndrome, or drug withdrawal.

The seizures result with the traumatic brain injuries, strokes, and brain tumors because of their irregular electrical activity.

Since hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, or kidney or liver failure, can be involved in the case then genetic factors are needed, as well.

For instance, abrupt termination of certain subsidence substances and medications is among.

Lastly, the withdrawal of medications or drugs, sudden discontinuation or change of medication or substance, can also cause seizures as well.

The prognosis of persons with epilepsy is determined by several factors such as the type of epilepsy, its frequency, the age when seizures develop and the genetic factors.

In children, the first onset is associated with a good prognosis, which means that their epilepsy may not be as severe as in adults.

More frequent seizures make the patient’s prognosis grimmer.

Epilepsy that begins in the early phase of life is generally considered to have a better prognosis than those which begin in adult life.

These biological factors induced, such as in turn, may elevate this risk of drug-resistant epilepsies and other propositions should occur.

Early childhood (0-5 years old): At this stage of developmeny from birth to 5 years, 30-40% of all seizures are febrile seizures, the episode of which is initiated when there is a rapid rise in temperature, at times accompanied by other alarming clinical signs.

Older adults (above 60 years): The incidence of epilepsy in this category also trend upward, as notable cases such as the occurrence of a stroke, a primary brain tumor, or Alzheimer’s disease tend to happen more frequent.

A seizure refers to a sequence of tests to evaluate the neurological state of the person.

These tests encompass the neurological assessment, which measures the consciousness of individuals, responsiveness, muscle tone, reflexes, coordination, and sensation.

The examiner checks the head and neck for trauma; on the other hand, a cardiac exam specifically checks for abnormalities or arrhythmias.

A respiratory assessment performed, for dealing with breathing patterns and lung sounds, is used to identify any compromised state during the seizure.

Skin inspections are done to find out any skin injuries during a seizure.

The person might stay for a while in a postictal stage characterized by confusion, drowsiness, weakness, or other neurological signs.

Seizures can have different kinds of beginning, i.e., sharp, slow, abrupt, and latent.

Seizures that begin suddenly can make one lose consciousness or begin having convulsions with no warning.

Gradual seizures usually start with mild feelings until it becomes obvious.

Certain people can experience “aura” symptoms or “warning signs” such as sensory disturbances in the brain or mood changes before a seizure develops.

The postictal period includes confusion and tiredness after a seizure, and some with gradual resolution and some with quicker recovery.

Due to the urgency of seizure presentations, an immediate hyperbaric medical rescue is necessary to avoid complications and minimize the damage in the brain.

Epilepsy

Febrile seizures

Syncope

Metabolic disturbances

Structural brain abnormalities

Patients with reversible seizures may be discharged after appropriate interventions with adjustments to medication and follow-ups.

Noncompliant patients may need restarting antiepileptic drug regimens.

Alcohol withdrawal seizures patients can be discharged after appropriate treatment and observation with lorazepam administration reducing recurrence risk.

Adults experiencing first unprovoked seizure and returning to normal neurological function may not require immediate medical treatment but caution should be exercised until follow-up, testing, and reassessment occur.

Chronic seizure disorders can be treated with various medications including sodium channel blockers, GABA receptor agonists, GABA reuptake inhibitors, and glutamate antagonists.

For generalized convulsive status epilepticus the immediate seizure treatment should begin alongside stabilization and diagnostic procedures.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam are recommended as first-line medications but respiratory depression is a common side effect requiring careful monitoring for appropriate dosing.

Consultation with a neurologist is essential for effective treatment.

The Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) has concluded but the optimal second-line medication for benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus remains uncertain.

Second-line medications include valproate, fosphenytoin, and levetiracetam.

Advanced airway management and blood pressure support may be necessary in cases, where generalized convulsive status epilepticus persists.

The optimal treatment for refractory status epilepticus remains unknown but propofol or continuous benzodiazepine infusion in combination with other anesthetic medications.

ICU admission is typically necessary and accompanied by continuous EEG monitoring.

Neurology

One of the most crucial triggering consequences of seizures is bright lights, tension, sleeplessness, and some drugs.

Managing mealtimes, sleep patterns, and medication schedules is very important.

Removing all potentially dangerous objects from the area and obstructions is essential.

Ensure the possibility of developing a new approach to combine the aftereffects and stave off any pain that can result from injuries.

Medical alert wristbands containing already-installed data and a GPS locator can also be installed for extra safety.

An example of this would be if someone is timely crushed by the person delivering the seizure, especially if this is occurring in dangerous environments such as stairs or swimming pools.

Neurology

Carbamazepine:It is used in the therapy of neuropathic pain, in addition to stabilizing the neuronal membranes,as a result of the inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels.

Oxcarbazepine: It works like carbamazepine in treating foval and generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Neurology

Phenytoin: It works primarily by stabilizing the inactive state of voltage-gated sodium channels in the brain reducing the incidence of seizures.

Neurology

Phenobarbital: It enhances the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid, in the brain by binding to GABA-A receptors, which are ligand-gated chloride channels, thereby increasing the duration of chloride channel opening.

Neurology

Valproate: Sodium valproate is an anticonvulsant medication used in the treatment of various types of seizures, both focal and generalized.

It increases the concentration of GABA in the brain, by inhibiting degradation.

Neurology

Vigabatrin: For focal seizures, which originate in a specific area of the brain, vigabatrin can be effective either as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy.

Neurology

Levetiracetam: This drug functions by modulating the release of neurotransmitters, specifically by attaching itself to the synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain.

The dose to treat myoclonic seizures is 500 mg intravenously or orally two times a day and it may be enhanced every two weeks from 500 mg to 1500 mg two times a day.

Neurology

Ethosuximide: It is considered as a first-line treatment for for absence seizures which are also known as petit mal seizures.

Neurology

Resective surgery:This involves removing the specific area of the brain where seizures originate.

This takes place by removing a portion of the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, or other areas depending on the location of the occurrence of seizure.

Responsive neurostimulation:This considers implanting a device called a neurostimulator, which continuously monitors brain activity and delivers electrical stimulation to interrupt or prevent seizures.

Corpus callosotomy:In some cases of severe epilepsy, that originates at same time directly from both hemispheres of the brain, the band of nerve fibres that connect the two hemispheres, the corpus callosum may be fragmented in surgical procedures to prevent seizure from spreading between the hemispheres.

Neurology

The stage of assessment and diagnosis is mainly concerned with reviewing medical records in detail, physical examination as well as other diagnostic procedures like electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography to determine the nature and origin of seizure.

Persons with epilepsy or even other types of chronic seizure disorders are commonly given these kinds of antiepileptic medications.

More consistency within the lifestyle, for instance, good regular sleep, better control of the stressful environment, and the avoidance of triggering factors are good aids in reducing seizure frequency.

Regular follow up and monitoring is necessary so that the treatment plan can be maintained on the correct track.

Seizure Medications – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

Seizures are electrical disruptions in the nervous system that cause altered mental phenomena, dislocation, motor action, and consciousness in some frightened patients.

Abnormal and excessive electrical signals in brain neurons cause a short-term disorder in brain activity due to abnormal electrical signals.

Partial seizures are common in adults which is characterized by initial activation in a specific area of the cortex.

They often present with symptoms like motor or sensory phenomena.

Generalized seizures occur from widespread cortical activation at onset of partial seizures.

This discourse discusses the assessment and treatment of seizures emphasizing the interprofessional team role in improving patient outcomes.

It also discusses the timing for differential diagnosis and evaluation methods.

Epilepsy incidence in North America ranges from 16 to 51 cases per 100,000 person-years with prevalence rate ranging from 2.2 to 41 cases per 1000.

Partial epilepsy accounts for up to two-thirds of new cases with higher incidence in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

25% to 30% of new-onset seizures are provoked and secondary to another cause.

Epilepsy incidence peaks in younger and older age brackets with cerebrovascular disease leading to cause among older individuals.

Excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the brain control the generation of signals and suppression of activity otherwise.

A balance between these two forces is present in a healthy brain, but it may be disturbed by depression of inhibitory system or exaggeration of excitation.

The reduction of hyperexcitability may be associated with reduced GABA function or increased glutamate sensitivity of the receptors.

However, when a group of neurons is in the hyperexcitable condition, they become persistently overexcited and, as a result, they spark multiple high-frequency action potentials.

Those axons increase the likelihood of repetitive electrical discharges by the neurons, triggering a seizure in non-related areas of the brain.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder, which leads to irregular electrical impulses in the brain.

It can be triggered by different life events, such as head injury, stroke, brain tumors, heredity, metabolic syndrome, or drug withdrawal.

The seizures result with the traumatic brain injuries, strokes, and brain tumors because of their irregular electrical activity.

Since hypoglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, or kidney or liver failure, can be involved in the case then genetic factors are needed, as well.

For instance, abrupt termination of certain subsidence substances and medications is among.

Lastly, the withdrawal of medications or drugs, sudden discontinuation or change of medication or substance, can also cause seizures as well.

The prognosis of persons with epilepsy is determined by several factors such as the type of epilepsy, its frequency, the age when seizures develop and the genetic factors.

In children, the first onset is associated with a good prognosis, which means that their epilepsy may not be as severe as in adults.

More frequent seizures make the patient’s prognosis grimmer.

Epilepsy that begins in the early phase of life is generally considered to have a better prognosis than those which begin in adult life.

These biological factors induced, such as in turn, may elevate this risk of drug-resistant epilepsies and other propositions should occur.

Early childhood (0-5 years old): At this stage of developmeny from birth to 5 years, 30-40% of all seizures are febrile seizures, the episode of which is initiated when there is a rapid rise in temperature, at times accompanied by other alarming clinical signs.

Older adults (above 60 years): The incidence of epilepsy in this category also trend upward, as notable cases such as the occurrence of a stroke, a primary brain tumor, or Alzheimer’s disease tend to happen more frequent.

A seizure refers to a sequence of tests to evaluate the neurological state of the person.

These tests encompass the neurological assessment, which measures the consciousness of individuals, responsiveness, muscle tone, reflexes, coordination, and sensation.

The examiner checks the head and neck for trauma; on the other hand, a cardiac exam specifically checks for abnormalities or arrhythmias.

A respiratory assessment performed, for dealing with breathing patterns and lung sounds, is used to identify any compromised state during the seizure.

Skin inspections are done to find out any skin injuries during a seizure.

The person might stay for a while in a postictal stage characterized by confusion, drowsiness, weakness, or other neurological signs.

Seizures can have different kinds of beginning, i.e., sharp, slow, abrupt, and latent.

Seizures that begin suddenly can make one lose consciousness or begin having convulsions with no warning.

Gradual seizures usually start with mild feelings until it becomes obvious.

Certain people can experience “aura” symptoms or “warning signs” such as sensory disturbances in the brain or mood changes before a seizure develops.

The postictal period includes confusion and tiredness after a seizure, and some with gradual resolution and some with quicker recovery.

Due to the urgency of seizure presentations, an immediate hyperbaric medical rescue is necessary to avoid complications and minimize the damage in the brain.

Epilepsy

Febrile seizures

Syncope

Metabolic disturbances

Structural brain abnormalities

Patients with reversible seizures may be discharged after appropriate interventions with adjustments to medication and follow-ups.

Noncompliant patients may need restarting antiepileptic drug regimens.

Alcohol withdrawal seizures patients can be discharged after appropriate treatment and observation with lorazepam administration reducing recurrence risk.

Adults experiencing first unprovoked seizure and returning to normal neurological function may not require immediate medical treatment but caution should be exercised until follow-up, testing, and reassessment occur.

Chronic seizure disorders can be treated with various medications including sodium channel blockers, GABA receptor agonists, GABA reuptake inhibitors, and glutamate antagonists.

For generalized convulsive status epilepticus the immediate seizure treatment should begin alongside stabilization and diagnostic procedures.

Benzodiazepines like diazepam are recommended as first-line medications but respiratory depression is a common side effect requiring careful monitoring for appropriate dosing.

Consultation with a neurologist is essential for effective treatment.

The Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) has concluded but the optimal second-line medication for benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus remains uncertain.

Second-line medications include valproate, fosphenytoin, and levetiracetam.

Advanced airway management and blood pressure support may be necessary in cases, where generalized convulsive status epilepticus persists.

The optimal treatment for refractory status epilepticus remains unknown but propofol or continuous benzodiazepine infusion in combination with other anesthetic medications.

ICU admission is typically necessary and accompanied by continuous EEG monitoring.

Neurology

One of the most crucial triggering consequences of seizures is bright lights, tension, sleeplessness, and some drugs.

Managing mealtimes, sleep patterns, and medication schedules is very important.

Removing all potentially dangerous objects from the area and obstructions is essential.

Ensure the possibility of developing a new approach to combine the aftereffects and stave off any pain that can result from injuries.

Medical alert wristbands containing already-installed data and a GPS locator can also be installed for extra safety.

An example of this would be if someone is timely crushed by the person delivering the seizure, especially if this is occurring in dangerous environments such as stairs or swimming pools.

Neurology

Carbamazepine:It is used in the therapy of neuropathic pain, in addition to stabilizing the neuronal membranes,as a result of the inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels.

Oxcarbazepine: It works like carbamazepine in treating foval and generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Neurology

Phenytoin: It works primarily by stabilizing the inactive state of voltage-gated sodium channels in the brain reducing the incidence of seizures.

Neurology

Phenobarbital: It enhances the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid, in the brain by binding to GABA-A receptors, which are ligand-gated chloride channels, thereby increasing the duration of chloride channel opening.

Neurology

Valproate: Sodium valproate is an anticonvulsant medication used in the treatment of various types of seizures, both focal and generalized.

It increases the concentration of GABA in the brain, by inhibiting degradation.

Neurology

Vigabatrin: For focal seizures, which originate in a specific area of the brain, vigabatrin can be effective either as monotherapy or as adjunctive therapy.

Neurology

Levetiracetam: This drug functions by modulating the release of neurotransmitters, specifically by attaching itself to the synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain.

The dose to treat myoclonic seizures is 500 mg intravenously or orally two times a day and it may be enhanced every two weeks from 500 mg to 1500 mg two times a day.

Neurology

Ethosuximide: It is considered as a first-line treatment for for absence seizures which are also known as petit mal seizures.

Neurology

lamotrigine: This can be used as an adjunctive therapy in treating absence seizures.

Neurology

Resective surgery:This involves removing the specific area of the brain where seizures originate.

This takes place by removing a portion of the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, or other areas depending on the location of the occurrence of seizure.

Responsive neurostimulation:This considers implanting a device called a neurostimulator, which continuously monitors brain activity and delivers electrical stimulation to interrupt or prevent seizures.

Corpus callosotomy:In some cases of severe epilepsy, that originates at same time directly from both hemispheres of the brain, the band of nerve fibres that connect the two hemispheres, the corpus callosum may be fragmented in surgical procedures to prevent seizure from spreading between the hemispheres.

Neurology

The stage of assessment and diagnosis is mainly concerned with reviewing medical records in detail, physical examination as well as other diagnostic procedures like electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography to determine the nature and origin of seizure.

Persons with epilepsy or even other types of chronic seizure disorders are commonly given these kinds of antiepileptic medications.

More consistency within the lifestyle, for instance, good regular sleep, better control of the stressful environment, and the avoidance of triggering factors are good aids in reducing seizure frequency.

Regular follow up and monitoring is necessary so that the treatment plan can be maintained on the correct track.

Seizure Medications – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

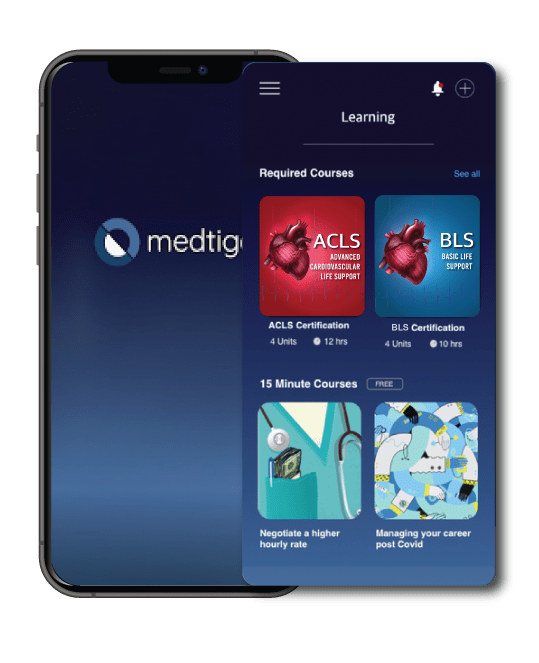

Both our subscription plans include Free CME/CPD AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

On course completion, you will receive a full-sized presentation quality digital certificate.

A dynamic medical simulation platform designed to train healthcare professionals and students to effectively run code situations through an immersive hands-on experience in a live, interactive 3D environment.

When you have your licenses, certificates and CMEs in one place, it's easier to track your career growth. You can easily share these with hospitals as well, using your medtigo app.